Last updated on March 4, 2013

“The heart is more deceitful than all else and is desperately sick; who can understand it?

Jeremiah 17:9

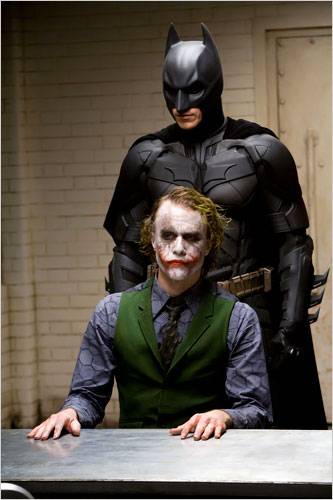

Having watched the Batman movies recently, it’s got me thinking: why do good people like to watch evil people do bad things? And why aren’t most video game villains memorable?

It’s an interesting question, made moreso by the fact that Christians, according to the Bible, are to shun evil and never to associate with it in any form. 1 Corinthians 15 (and more verses that you can find on your own, dear reader) state this clearly:

33 Do not be deceived: “Bad company corrupts good morals.” 34 Become sober-minded as you ought, and stop sinning; for some have no knowledge of God.I speak this to your shame.

We’re not supposed to judge people, but we also must be careful not to adopt the “ways of the world”. It is evil that leads them into further corruption, and only Jesus Christ’s saving grace can take them out. In entertainment media, however, we usually have a villain as an all-too-common addition to a narrative. If you don’t have a good and a evil, or at least shades of gray, than there’s no easy way to create conflict. Certainly, there’s plenty of films that work because the central conflict is more neutral, but video games tend to give us a good and an evil.

There’s two types of evil characters: those that are evil simply for the sake of evil and those who are evil for actual reasons. Let’s use the Batman movies (again) as an example. Ra’s al Ghul (Emile Ducard, if you want to be picky), in the first film, is evil by virtue of his methods. He wants to bring justice to the world, and that justice only comes about through “balance”. At times in history, civilization has tipped the balance towards evil; the League of Shadows exists to tip that balance back so that humanity can continue to thrive. Do they sacrifice many human lives to the progress of history? Yes indeed. Do they believe that such actions are necessary? Absolutely. The philosophy of “the ends justify the means” isn’t evil inherently, but its abuse obviously leads down a slippery slope (see: The Dark Knight Rises, which uses the original intention of the League to fulfill the ends of revenge rather than justice. It’s a subtle move on Nolan’s part).

The second type, though, frightens us infinitely more. The Joker in The Dark Knight Rises embodies an evil that doesn’t give reasons, nor does it care. Rather, it’s only intention is destruction, deceit, and horror. You can’t reason with this kind of evil; it must be confronted, contained, and destroyed. Yet, unlike Ra’s al Ghul, to whom we can understand and relate, the Joker becomes a much more interesting character by virtue of his mystery. He has a motivation; that motive is anarchy and destruction. Chaos is the natural order, and civilization disrupts this balance. To give so many words to the Joker’s philosophy, though, puts it at too high a level. It’s an evil that we can’t explain, so we call it “nihilism” – the lack of meaning and value in life.

I would contend that the Joker doesn’t even go that far. The best real life example is the child molester. Instead of identifying this as an evil in itself, we explain this by natural forces – he was born this way, he was raised in an abusive household, etc. But what if this horrible act was a willing, conscious decision on their part? What if they want to do that simply because it gives them pleasure? They don’t think it’s evil or good; it’s just something they want to do as a sensual experience. It’s not just the reverse of what we hold dear, but its opposition. Everyone wants to place the blame on a villain who has reasons, or can explain their actions. That’s something we can understand; once the villain moves beyond our constructs of morality, however, we cannot reckon the existence of such a person.

Of course, this doesn’t explain why we all think Heath Ledger did an excellent job as the Joker, nor does it explain why Ra’s al Ghul isn’t that memorable. It is the element of deception that truly marks the divide. Ra’s al Ghul isn’t deceptive, for the most part; sure, he has hidden plans, but these accord with his stated intentions. There’s no mystery to his plan because it isn’t meant to be mysterious; it’s meant to be effective. When he appears again at the end of Batman Begins, we’re not really surprised that his plan is the destruction of Gotham – there’s no ambiguity because his objective (and the League of Shadows by association) was plain and obvious from the get-go. He doesn’t hate good; he merely uses evil methods to reach that end.

Contrast this with the Joker. Who is he? No one knows. Why does he do what he does? Apparently to force Gotham into a series of moral dilemmas, each of which force someone to make a sacrifice. How do you stop him or motivate him? We don’t find out in the film. He would never stop doing what he did unless he was stopped. He continually deceives everyone into making the wrong decisions, or forces them into a situation where there isn’t a right choice from society’s standards. He forces the hero into his world, where rules and norms don’t exist at all. It’s the reason why Batman needs to analyze every communication device in Gotham to find this man. There is no bargaining and no winning; one of them will become the victor, and the other the loser. Batman does represent good, even in an imperfect sense, while the Joker represents evil itself.

Evil is much more likable than “unlawful good”, to put it in D&D terminology. Evil tries to deceive one at every turn; that’s why sin is so attractive. If it wasn’t, why do it? The Garden of Eden shows the serpent goading Eve into eating the fruit by appealing to her vanity. Sin makes great promises with an empty payoff. Evil becomes deception incarnate, not for some greater purpose, but simply TO deceive. This is why I lament the loss of the “evil” character in narratives. We need to show evil in its true colors, not just as “good doing evil for good’s sake”. That makes a bevy of assumptions of “complexity”, when it’s not that complex at all. Throughout time, cultures in world history have personified evil in various forms, all of them sharing that central characteristic: evil intends destruction and deceit for no particular reason (see Jeffrey Burton Russell’s five part book series on evil).

That’s why, when we like a villain, it’s because they seduce us into liking them. That’s the whole point! A villain isn’t effective unless he/she/it seduces us into their world, to take a little walk on the wild side or make that first step into Hell. If they don’t, they’re not memorable. It’s not surprising that writers and screenwriters alike know how to portray a great evil character that appeals to us. It is because they know evil’s true face. 2 Timothy 3 talks about the end times and what evil will look like in those days:

3 But realize this, that in the last days difficult times will come. 2 For men will be lovers of self, lovers of money,boastful, arrogant, revilers, disobedient to parents, ungrateful, unholy, 3 unloving, irreconcilable, malicious gossips, without self-control, brutal, haters of good, 4 treacherous, reckless, conceited, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, 5 holding to a form of godliness, although they have denied its power; Avoid such men as these. 6 For among them are those who enter into households and captivate weak women weighed down with sins, led on by various impulses, 7 always learning and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth. 8 Just as Jannes and Jambres opposed Moses, so these men also oppose the truth, men of depraved mind, rejected in regard to the faith. 9 But they will not make further progress; for their folly will be obvious to all, just as Jannes’s and Jambres’s folly was also.

Evil turns the good into bad. We fear this kind of evil more than anything else. It’s the evil that Satan represents: evil incarnate. There’s a whole host of stopgaps between point A and point B, but it has to start somewhere, even if we’re not privy to the details. It’s the evil that goes against everything civilization represents: law, order, civility, and a certain ideal of right and wrong. If the law is written on men’s hearts, than an evil man can’t even begin to understand the law itself; he has absolved it from his memory, and placed his own actions as the measure by which all else functions. If Satan is a fallen prideful angel who wished to place himself above God, than this encapsulates it perfectly.

Video games, unfortunately, merely insert the form, but not the content. Once you’ve made evil the result of an insane mind, then it’s no longer evil. Sephiroth, then, doesn’t function as a true villain. If he’s insane, he is merely misguided, rather than a force of evil. The same goes for Sin/Jecht in Final Fantasy X; it’s the wrong method to the right solution, to save humanity from destruction every ten years still isn’t the correct result. Final Fantasy VIII brings a villain whose motivations we don’t truly understand; the same goes for Final Fantasy XIII as well.

There’s not many video game villains that we remember or that seduce us into their world. They lack that conscious faculty that makes them “mad” from the perspective of good, not crazy in themselves. In video game terms, that’s why Kefka strikes me as a much more memorable character than most any Final Fantasy villain. Why? Because, surprise, he’s evil itself. He deceives, insults, and parades his way through Final Fantasy VI as the villain by first glance. We know he wants to gain power and kill people, but we’re not sure how until the midway point – when it does happen, we’re surprised and shocked.

Kefka’s motivation: destroy everything. Why? Just because. Yet his personality convinces us to like him even in the face of such a terrible worldview. Isn’t that interesting? When evil actually works effectively in fiction, it works just like real life. We are drawn to it because of our sinful nature, even unknowingly. That’s what makes a villain so effective; that he/she makes you like them even as they do terrible things. Satan’s got the same deal going, I’d wager.

The evil found in Christianity is that which has no explanation. Evil for evil sakes frightens us, yet attracts us for all the wrong reasons. The will and movement of the heart can’t be discerned, and it is over this that we must be watchful. As 2 Peter 2 says:

18 For speaking out arrogant words of vanity they entice by fleshly desires, by sensuality, those who barely escape from the ones who live in error, 19 promising them freedom while they themselves are slaves of corruption; for by what a man is overcome, by this he is enslaved.