Last updated on December 25, 2013

24 In those days Hezekiah became mortally ill; and he prayed to the Lord, and the Lord spoke to him and gave him a sign. 25 But Hezekiah gave no return for the benefit he received, because his heart was proud; therefore wrath came on him and on Judah and Jerusalem. 26 However, Hezekiah humbled the pride of his heart, both he and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, so that the wrath of the Lord did not come on them in the days of Hezekiah.

2 Chronicles 32

Often, it is thought that the Old Testament remains the “lesser” of the two books. God sounds and acts completely different between the two narratives, one as a stern and unforgiving bookkeeper of the Law, the other a compassionate guy who wanders around telling indecipherable parables while also telling them to hug their enemies.

Granted, the Old Testament Law seems harsh from our post-Christian perspective. The whole of the legal document places taxing restrictions on human action, everything from marriage to the correct forms of sacrifices. Many of them involve the death penalty, or stoning, or perhaps even becoming a pariah from the community. God’s people lived under those rules because they set them apart as God’s people. They distinguished themselves through the worship of one God, YHWH, who wished for a holy and righteous people to emerge out of Israel. This would involve sacrifice and determination, as well as a healthy dose of grace.

We could also state, further, that the laws in here describe the maximal punishment for the crime, not exactly the common prescription. Why did David not execute Shimei, the man who cursed him, or Joab, the man who killed his (admittedly disobedient) son? As king and enforcer of God’s law, he could, but didn’t.

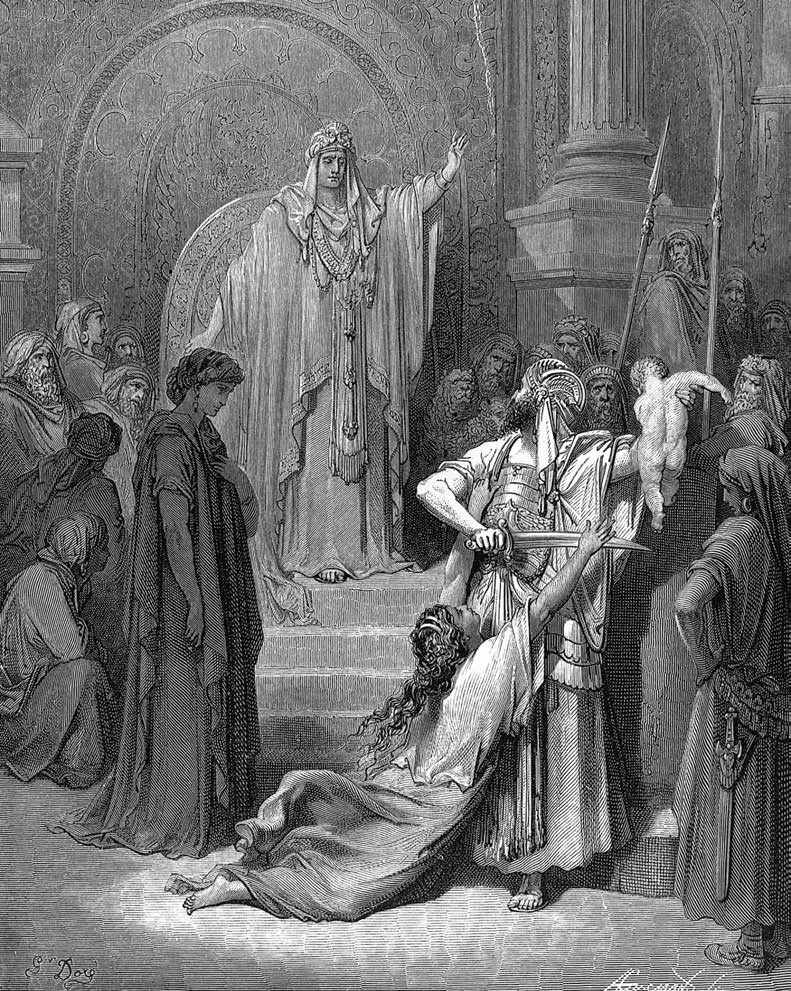

Why would the Bible commend Solomon for not executing violators of the Law, when they very well could have? He could have executed Adonijah once he was declared king, but he chose not to do it. He could have executed the woman who lied about stealing the son, but he didn’t do it.

NOTE: I am here leaving out Solomon’s executions that David compelled him to perform as a last will in testament – these were not his decisions, as it was generally assumed you do this as a continuation of the family line. Clean up, in other (terse) words. Besides that, he only executed them after they proved themselves deserving of that punishment (Shimei was granted the blessing of a vow that he would not die if he obeyed, and he still violated it ).

In any event, people deserve second chances. Yes, they will receive punishments from God or government, that much appears certain from the Biblical text, but the general tone (as in the Hezekiah quote above) shows that God will show mercy for a humble and contrite heart. God does not want to kill people anymore than he wants them to fall into eternal damnation. Why do we so often think that we must do that job for Him?

In fact, I’d call the New Testament a much more harsh book. Compare and contrast Leviticus 19:18 to Matthew 5:43-44.

You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the sons of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself; I am the Lord.

——

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ 44 But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you…

The first takes a much more lenient approach to the situation; we can assume from the context that “neighbor” is a bit less strong than “enemy”. God wants the Israelites to love their neighbors, their fellow Jews, as they would themselves. Treat others as you would like to be treated – in our modern world, we call this the Golden Rule. Can you find someone on earth that doesn’t agree with this?

But Jesus adds intention and further commitment on top of the command (hence fulfilling it, as we know). Not just to love your neighbor, but your enemy, and then to pray for him as he persecutes you. That’s a pretty wide gap, an addition onto the framework already existent. Jesus makes explicit what was implicit in the original Torah text, and then takes it one step further. In divorce, for example, Jesus says that Moses made an allowance for human sinfulness in this case. But will Jesus?

7 They *said to Him, “Why then did Moses command to give her a certificate of divorce and send her away?” 8 He *said to them,“Because of your hardness of heart Moses permitted you to divorce your wives; but from the beginning it has not been this way. 9 And I say to you, whoever divorces his wife, except for immorality, and marries another woman commits adultery.”

Of course he will. He did, after all, take the sin of the world and died on a cross to defeat death forever. Even as we find ourselves freed from the Law through Christ, it also remains an integral part of the faith.

A lot of Jesus’ words reveal the difference between doing the action, versus the intention for said action. In that sense, the New Testament comes down MUCH more harshly than the Old Testament. Heck, we mostly just talk about the OT laws (of which there are 636, mind) where people get put to death, and yes, there’s a lot of them, but many of them just require sacrifices to fix. Not gonna get into the distinction between those sacrifices, but much better than being condemned for thinking something, right?

Even so, Jesus never goes beyond what’s said in the Old Testament; he’s merely working out the consequences, as God explains them. Of course, Jesus also introduced the concept of Hell and condemnation in an eternal afterlife, so you could say He sounds much more judgmental by comparison to the Old Testament. The Old Testament isn’t wrong for not mentioning it, but God chose not to place it there.

So, in the end, it seems strange to me that we often aren’t willing to look at the Old Testament (or the First Testament, depending) on equal footing. It requires a lot more effort to understand it (the New Testament’s just easier to co-opt into our interpretive lens), but it is certainly worth the effort. How did we get to this point in Christianity? What did God do before all that to solve the problem of sin? All that information’s contained in the 39 books preceding the first Gospel. They’re there for a reason.