Last updated on March 29, 2014

You should read Do Video Games Tell Stories? – Control first.

You are from God, little children, and have overcome them; because greater is He who is in you than he who is in the world.

1 John 4:4

That something else is empowerment. The “stories” that a narrativist (one who see video games primarily in the vein of narrative, obviously) believes as the height of video games only work on a ponderously small subset of the overall game-playing demographic who want to submit. They take away power, while video games usually empower. When I say “empower”, I do mean what you think I mean: since most people believe that they’re not in control, video games provides them with a space to feel control over something in a distinct environment with clear objectives. To deny this is foolish.

The problem with dis-empowerment in game, then, comes from the divide between a story and a game. A story must be told. You do not do a story. Video games are all about doing, and providing a player with a space for doing. The problem, then, is that video game developers seem hell-bent to make video games into something they’re not. Rather, what they can do, and Tadhg Kelly describes this best, is establish “storysense”:

Storysense is not unique to games. Marketing stories, poems, some albums such as Jeff Wayne’s The War of the Worlds, music videos, Disneyland rides and films like Koyaanisqatsi are all examples of works that have great storysense. They convey the feeling of a story, glimpses of key moments, develop a theme and a metaphor. Like impressionism compared to formal painting, they hint rather than show or tell.

Storysense is different to storytelling. Plot and character development are creative constants of dramatic narrative, but videogames are not a dramatic art form. Plot doesn’t really matter, nor character development. The player does not have to be told who her doll is or what she is supposed to feel. There are no acts, and the motivations of enemies don’t really have to be explained.

Techniques of storysense revolve around portraying a world in motion. Short cut scenes that set tasks, scrolls and other discoverable items, user interface elements, alongside dialogue and incidentals are all key tools. The idea is to keep the player on the move, interested in the world while at the same time fascinated by the play.

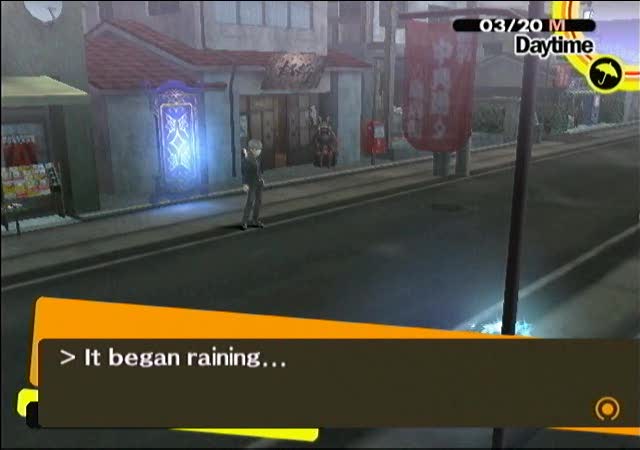

This occurs in so many games that I can’t even count. However, I’ll point out an especially relevant example to me at the moment: Persona 4. P4 establishes the bare hint of a world by reliving high school. Well, the sort of high school where you’re popular, a good student, involved in every after school activity or part-time job, and also slay demons, solve mysteries, and save the universe. But P4 succeeds by setting every single task as a clear benefit to your character. At the same time, it slowly reveals hints to the plot and a fuller understanding of the world in which the player explores. In other words, it seems like you can do a lot of stuff! The world feels alive without being alive.

Social Links add greatly to this feel. Call them “plots within a plot”, each of your Social Link makes you more powerful in combat, but also goes through its own dramatic arc with your as spectator. Think of these little vignettes as rewards for correct responses and certain in-game events. Persona frequently provides intangible (story, dialogue) and tangible (new Persona use, equipment upgrades, party members, sidequests, etc) rewards to goad the player along. Whether or not you accomplish real or imagine difficulties, it explains why a 70+ hour game developed such a strong player base.

One notable aspect comes in the arbitrary time limits; you can only improve yourself so much before going into the various dungeons. You must complete them and defeat the boss within a certain time period (i.e., before the fog comes), or someone in the real world will die. The game emphasizes this through the contrast between normal days and rainy days; happy, fun-time Jpop plays on normal days, while rain leaves you with an eerie silence of pattering precipitation heralding a possible murder.

All these elements build on the “storysense” of the world. I will guess the plot devolves into standards tropes and stereotypes. It will not represent the highlight of storytelling, but it weaves a rather good yarn that hits all the high points. The player’s character exists just to prod the story along and make you see yourself as the actor, shaper, and mover in the story. Illusory, of course, but the bare hints of a world beyond your screen convince you of this empowerment. I am not the player character, of course; I’m just controlling the person who does these things. I simply express my will through this on-screen doll.

If P4 didn’t do this, and continually took the reigns away from me without my will to continue things to the end, then it would ultimately fail. A traditional dramatic arc would pummel its protagonist with difficulties he may/may not overcome. It would require that the game telegraph intended emotional cues like a movie or book (i.e., telling us how to feel in the way the best stories can, by doing it subtly). But video games aren’t like that; I see what I want to see, and removing that choice to explore the designed world isn’t inherently interesting.

What if a game like Thief didn’t let you steal things from poor and rich people alike? How weird would that be? We often assume the game either doesn’t care, has a particular motivation in placing certain actions, or that the “ludonarrative dissonance” takes you out of the experience. Isn’t the game about being a Thief? How much more natural could stealing be in that context, regardless of who cares about it?

There’s a strange divide between our brains, not due to training or whatever, but just via design. My play brain, the one doing all the playing, conflicts with my art brain, which appreciates all the wonderful aesthetic stuff. Sometimes, one gets confused with the other, and that’s how we end up in quite a mess. Both are required, but games favor the former predominantly over the latter. The story becomes a background when I’m trying to survive; the moral ambiguities of the narrative give way to a kill or be killed world. Proper empowerment does not mean stifling the play brain, but by challenging the play brain so that the aesthetic portions melt away. One exists to grip, and the other keeps them locked into the experience.

If the mechanics interest the player, they will come. If merely the tightly-controlled story limits your “interaction” (hey, David Cage, QTEs are still boring!), then they will lose interest. A video game developer, then, isn’t primarily a storyteller. They make worlds. And these worlds need to sustain your interest through their systems, not through your adept storytelling which strait-jackets the game’s ability for self-expression.

Like God does to us, a good designer knows how to make us feel powerful. God does it for real, of course, but the principle is very much the same both psychologically, physically, and spiritually. But God makes us strong in both strength and weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9); that’s not something a video game can ever do, and really shouldn’t try. Other mediums fit well in terms of making disempowerment relatable and vicarious, but dis-empowerment in video games will always be an illusion and feel disingenuous. You’re in power; you just don’t know it. The game will not progress without you.

I can always shut the game off!