Last updated on August 15, 2013

3 “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

4 “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.

5 “Blessed are the gentle, for they shall inherit the earth.

6 “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.

7 “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy.

8 “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

9 “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

10 “Blessed are those who have been persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

11 “Blessed are you when people insult you and persecute you, and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of Me. 12 Rejoice and be glad, for your reward in heaven is great; for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

Matthew 5

Jesus Christ in the Beatitudes tells the people that things aren’t as they seem, that reality’s real construction lies underneath all our culture constrains us to think. The Savior calls for us to imagine this idea, for we cannot see it with our physical eye. Our mind’s eye, forever clouded by sin and culture, can’t see the magnificence either. But our spiritual eyes? Surely as the day we convert and see thing rightly for the first time, so do we finally see a new vision of reality not dependent on what we see. Faith requires imagination; one does not exist without the other (and if you need evidence of this, just look at Isaiah 11 and please tell me how that works without imagination).

Video games, in this sense, disturb me a bit. What are they but reflections of a reality? All media present this to a degree, but video games endeavor to force interaction and involvement with a series of complex, interrelated systems. Their initial format (as in the earliest games) contains symbolism and focus – they knew what they were, games, and followed in the tradition of all previous. They weren’t all intuitive; developers knew they could plop an exhaustive manual on your lap to discuss the rules and mechanics at play. The aesthetics merely complemented the system.

You didn’t need a whole lot of context; you had imagination to cover that. Early video games gave us representations, and our young minds filled in the blanks. It was a wonderful time! Games afforded you fun mechanics and time to explore those mechanics to the fullest. Impressionable minds would blow things completely out of proportion to their importance, and the good guys HAD to save the day. Kids tap into their imagination much more easily than adults. There’s a reason why nostalgia pops up so often: because, at the time, it seemed like everything was awesome, regardless of how dumb it really was. The modern cynicism and irony directed towards everything and anything tells us that much: we are no longer allowed to like dumb things. That’s honestly too bad!

The imagination does not end in the game; it creates a whole reality of play and wonder at the world outside. It is an aid to it, not a detriment. I remember becoming involved in this stuff precisely because it gave me the room to think and imagine for myself. We could fight the battles and save the princess, and the video games sparked these ideas. The simplest stories appeal to the child because a child understands them, just as much as he understand Christianity. You can explain the whole Gospel in a sentence or two, and the child will take it on good faith and imagination. That’s rather remarkable, isn’t it?

Video games began in this model of other games, and they didn’t know any better, in their innocence. What a time it was, really! As the medium grew (and the “gamers” grew up along with it), things changed. Games looked more and more like reality; we got a little confused with the mechanics, because it looked like reality and didn’t function like it. We needed tutorials, and we need intuitiveness. If it doesn’t have these characteristics, the game’s “bad” for not teaching you the rules. It’s a strange development, but one made necessary by dipping into the realm of reality simulation. We can’t give the developers any slack, nor have we. The indie game movement feels like a direct counter to this, instead replicating the game of old as a direct contrast (although it’s clear that “games of old” means Nintendo, not Atari or their predecessors).

So it is that our video games, somehow, turned into reality simulators. But should video games attempt to become simulations of reality?

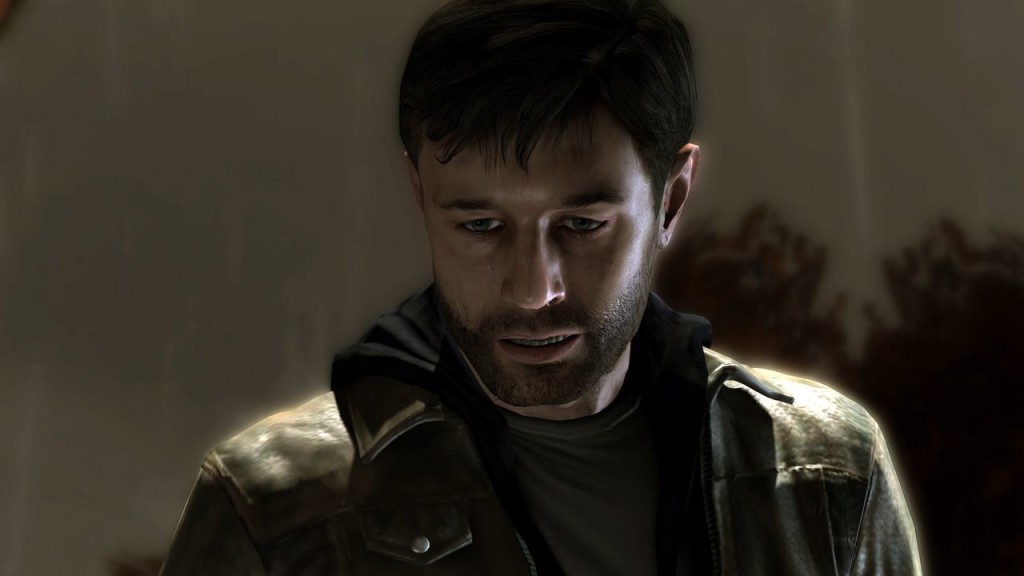

This question strikes me as a rather interesting one, and an increasingly relevant one. At one end, the market focused towards more mainstream audiences desperately wants, for some reason, to create video games that emulate reality. Many of the best selling video games of all time now sit squarely in this category, with Call of Duty bearing most of the weight (and maybe some Heavy Rain to go along with it). To clarify: when I say “simulations of reality”, I don’t mean as a 1:1 correspondence with our reality. Rather, I mean mechanically as well as aesthetically.

Take Heavy Rain as a good example of this. Although I could call it an incessant sequence of quicktime events (press the button now! Swirl that analog stick or character dies!), that’s unfair to David Cage’s vision. Surely, I am stating something true about the game, but he tried to place humanity into a video game. Did he fail rather miserably and descend into the scary uncanny valley one too many times? Absolutely! Did some people feel touched, and felt like he succeeded in that aim? Absolutely! And why did they like Heavy Rain?

Well, because it wasn’t much of a game at all. Rather, he tried to replicate something that actually happens in the real world, and then translate this into an interactive experience. On one level, it has rules and systems that tie into its aesthetic presentation. On the other hand, the aesthetic presentation limits how interesting and how interactive those mechanics truly function. The developer needs to constrain their audience into a series of predictable actions to reach that predetermined result, even if the player’s offer choice as to which result. For anyone familiar with reality, that is just NOT an interesting set of choices, all said. There’s no set of mechanics that can truly do this without constraining a player’s choice or contravening their assumptions about life in general. Allow me to explain next time.

Also, sorry if Heavy Rain appears my constant whipping boy; it’s not intentional. The game just happens to represent the most prolific example of “interactive experience” I can imagine.