Last updated on March 17, 2015

Read the Introduction!

How Capitalism, At Least Ideally, Freed the Individual to Be His Own Patron and Master

Things went on like this for a long, long time – that is, until people started to question it. Why should only the rich, powerful, and the inheritors be able to create works for their own glory, that of a religion/state, or the public welfare? What about creating things for myself? The rise of the individual, I wager, began with the very same Renaissance I mentioned above and the emergence of “humanism”. Thousands of years passed without any changes, but the increase in literacy and learning in Italian city-states during the 1400s let a new class of elites emerge, those with funds from primarily mercantile efforts.

Merchants were not considered rich or powerful; rather, many viewed them as the dregs of society. And yet, they became some of the most powerful people on the planet (just take a cursory look at the Medici, or the Borgias). They, along with the philosophical movements of the time, began to stress the free thoughts of individuals and their private intellectual inclinations rather than society as a whole. We call this humanism, in contrast to today’s secular humanism, in that it was a Renaissance cultural movement that turned away from medieval scholasticism and revived interest in ancient Greek and Roman thought. The Greeks and Romans, as you know, established democracies and philosophical thought which primarily emphasized rationality. These are the seeds of the modern Western social context for art and its creation.

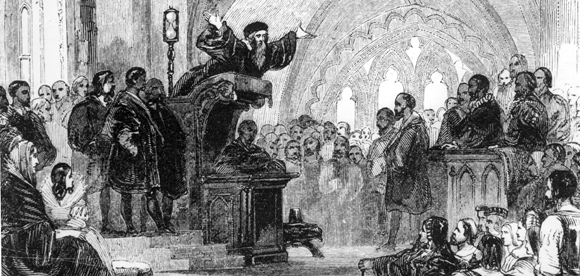

This emphasis on rationality and a questioning of the powers that be made people much more inquisitive. Why am I listening to this external authority? Why does one person control the thoughts and beliefs of so many? Why do I not get a vote, or a say, in how things are run? Free and independent thought rode freely through Europe. For Christians specifically, the roots of the Protestant Reformation lie in humanism, as rationality became a weapon to apply to the prevailing religious powers of the day. Why should we trust what the Pope says merely on the authority of his position, or just via tradition, or why the people are not allowed to read the Holy Scriptures themselves? Martin Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin (later on, of course) all thought the same thing, and religion ended up appropriating those same ideals of rational thought and establishing society based upon it.

People could, in effect, make things they liked to make. Obviously this transformation took a long time, but eventually the merchant way of life became our ideal, rather than the scum of the earth. Things got strange! I find modern art predominantly focused on the perspective of the individual precisely for these reasons, having adopted the merchant’s “take it all for myself” mentality in a less-than-wide context. Yes, those works revolve around the self, the self’s perspective, and communicating that self’s perspective to others. In fact, to put it succinctly, we might even call it selfish, or self-indulgent.

Views of the Reformation On Business

Or, at least, that might be the impression you often get reading the Reformers. In the popular imagination, Protestant Christianity opposed every kind of artistic expression. This is not true; taking the historical context of their writings into account, they reacted against a Catholic Church which took gaudy extravagance to new heights. They opposed the iconography and the use of art in the Church, but the difference is in intention, not wholesale condemnation of artistic works in general. To quote John Calvin:

But, as sculpture and painting are gifts of God, what I insist on is, that both shall be used purely and lawfully, that gifts which the Lord has bestowed upon us, for His glory and our good, shall not be preposterously abused, nay, shall not be perverted to our destruction.

Art and its works were not, as you might assume, the domain of the Church but outside of that sphere. Calvin only believed in the teaching of Scripture and the admission of the sacraments in the congregation, and only in a preaching context; the Word of God had an exclusive use in this fashion, and not many others. Still, art could enlighten us to a greater reality and bring delight to our hearts if God-centered. On the other hand, such works could be easily perverted in their own way. It is quite easy to sneak whatever messages or ideas you wish into a work. This is why Calvin makes the clarification that artistic works function under God’s laws, not man’s. They are communal in nature, meant to communicate a message through the vehicles of common song. This is probably why Calvin always emphasized music specifically in his writings:

The object of music is God and His creation. The glory of God and the elevation of man are its goal, and the inspired Psalms are its means. Since it is the goodness of God emanating through the universe that makes men sing, God ought to be the centre of man’s thoughts and feelings when he sings. Seriousness, harmony and joy must characterize our songs to God.

Art does not exist for personal expression, but for the glory of God. That, I think, presents a unique contrast to how we think of the arts today: as, in some sense, a solitary effort brought to life. Perhaps this is just too postmodern for my tastes, that the artist’s actual necessity to express does not come through (there is only the text? Really?). Perhaps this is because that artistic expression is misdirected.

However, and in a strange contrast, Calvin’s theology of work led, in some ways, to the establishment of modern business as we know it. Remember that in the 1600s, a time of upheaval in so many ways, economic stability crumbled. The breakup of the Roman Empire was followed by the establishment of city states, feudal holdings and the divided lands of kings. With divided resources and a lack of stability, subsistence living became the norm, and the Church became the pillar of the world in many senses. Profits and money were considered sinful vices (hence the earlier notion of merchants being evil),

Calvin, in contrast, believed in a theology of work that accepted profits and anything that came from them. Calvin taught that profits were the fruit of one’s labour — a person’s good work (let me make the distinction that profits are not a reward for good work – this is not prosperity gospel teaching). He believed charging interest for capital transferred injected moral legitimacy into business transactions – that you must pay what you owe until you pay off your debts. Being thrifty constituted a sort of instrumental piety; as God favored work and the fulfillment it naturally provided, using God’s gifts appropriately also pleased God. Ultimately, as with artistic works, all work only functions well if it naturally brings glory to God.

That, I think, makes the cleavage of video games between “art” and “business” so difficult. In video games, unless you design them for free, you must “sell” them – that remains the expectation of the culture. Video games did not arise out of purely artistic means – they exist to make money. And yet, that does not mean we need to reject that fact when producing something of value and artistic worth. Art and business can work together, but much of our negative perceptions rests on how we think of the realities of business, rather than the actual reality of their function.