Last updated on March 25, 2015

Read the First Three Parts!

Given all this, you might still imagine that businesses and corporations in the video games space hampered innovation and development in the space via the whims of focus groups and other metrics used to find out what’s best for an audience. This would be a fairly limited view of the whole structure; just take a look at some multi-billion dollars companies that are, by many, beloved. Blizzard, for example, continues to make tons and tons of money, and yet they fail to retain the negative reputation of, say, Electronic Arts, which people believe the Worst Company in the World several years in a row. What causes this fervor, negative or positive, to a company’s output and practices?

Much of this comes down to a company’s approach in forming public perception about themselves. In business terms, the way you perceive a company often comes down to their marketing management – the art and science of choosing target markets and building profitable relationships with them. In the modern world, businesses aren’t usually just production, product, or selling focused. Improving their processes in efficiency produces only an internal management effect, and thus proves no different to the customer. Improving the product, just making a better mousetrap, doesn’t inspire the customer to purchase more. Merely selling a product, and failing to develop a relationship with them, worked in the past but fails to work now. Modern business does not tell people what they want to buy; rather, businesses try to find, keep, and attract customers (NOT consumers) via creating, delivering, and communicating superior customer value.

Well, that’s the goal, anyway. Good companies treat video game players like customers, not just consumers. They know, with the rise of the Internet, that their customers can find, retain, and discover much more information than anyone ever thought possible in human history. As such, they cannot hoodwink the customer so easily; power in information is retained equally among both partners in the exchange relationships. Companies that see this have adjusted accordingly, seeking to meet the needs, wants, and demands of their targeted customer demographics (they can’t serve everybody on Earth, after all). The companies we like end up being the ones who deliver on satisfying customers better than their competitors. That also means they need to, in some way, predict your future needs and wants, which is where things get tricky for them and exciting for us, though!

Just for example, Ubisoft release Far Cry 3 in 2012 or so. That game iterated on the slow transformation of Far Cry from the original game’s linear single-player FPS inspirations, to the Africa open world of Far Cry 2 (with realistic damage and malaria!). However, between the second and third games, Assassin’s Creed exploded in popularity with the Ezio trilogy ( II, Brotherhood, and Revelations). Ubisoft had hit the vein of something dramatically effective in satisfying customer needs, and people clearly demanded more games in the same lane. As such, Far Cry 3 turned out much more like Assassin’s Creed, merely taking a lot of its mechanical elements into a first-person perspective; it also returned to the island theme with more nuance and interesting events just to satisfy fans of the original game. As such, it ended up a success itself, and future games in the series clearly took on that model.

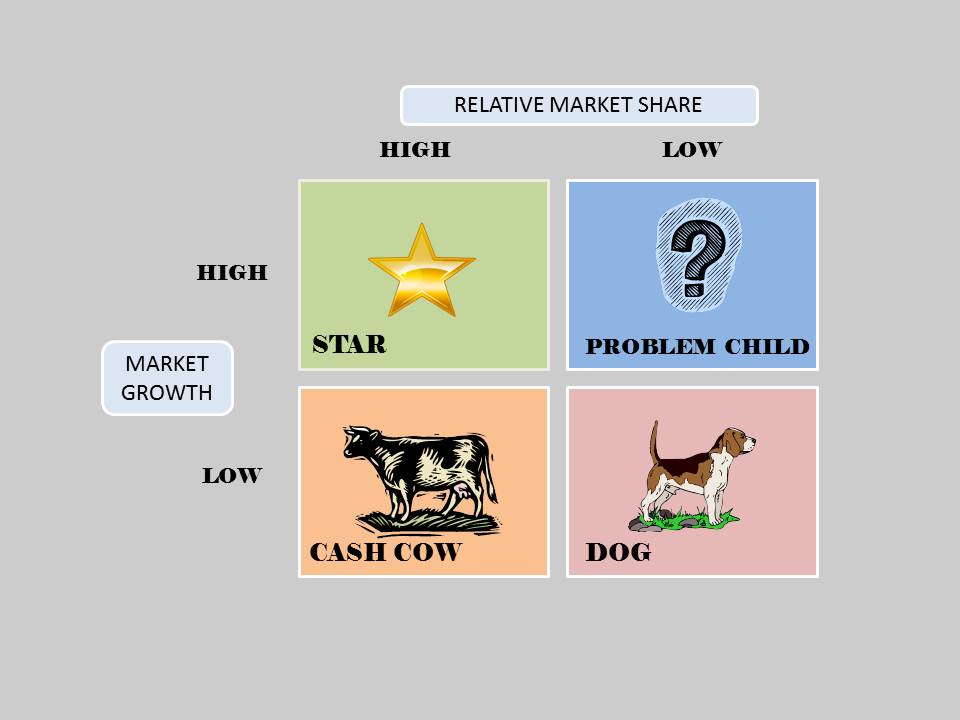

BUT, that success also means they will take smaller risks to test the waters and see what people want. Anyone familiar with the Internet know that there’s a nostalgia for the 1980s, from kids’ shows to music (synthwave is great, go look it up). As such, Ubisoft said “why not capitalize on this?” As such, when someone came up for an idea for a small spin-off game to Far Cry 3, Blood Dragon, they gave them the go-ahead to develop and create it. I’m sure a large enough demographic bought it and loved it (even if I wasn’t too impressed by the results), but companies need to take these kinds of risks to predict the customer’s needs in the future. The same goes for Ubisoft’s “Indie” department, which keeps throwing out smaller, innovative titles just to gauge customer interest. They can rely on their cash cows and stars while seeing whether those weird question marks will prove fruitful in the future

In no way do I say this to mean “making better games”. That, I think, is immaterial to a company’s function. A company cannot desire to fulfill ALL customer desires, because such a thing would put a company straight out of business. Rather, achieving an appropriate level of satisfaction, without quite going bankrupt, is their key goal. They have to make money to continue their existence, after all, and they can’t just cater to a single person’s whims and demands. I suppose that’s why I find certain games just don’t appeal to me at all these days – the wider the audience, the more likely you will minimally satisfy both everyone and no one at the same time. That’s why most video games companies target their games at specifically research demographics – they know they can both satisfy and (more importantly) delight their customers. Delighted customers turn out to be pretty devoted, eventually turning into evangelists for their products.

So, as you can tell from the reams of text on this, I really like specific games from specific companies. I am, as you might say, an evangelist for stylish combat action games like Bayonetta, and I will defend it to the death. I am that corporate evangelist, and I am a card-carrying member of the nonexistent Platinum Games club. That passion is exactly what a good marketing-driven, customer focused business wants. This is what creates gargantuan monsters like Blizzcon, cosplay, nerd culture conventions, you name it – they make people associate with brands, make them a part of their daily lives, and end up marketing the product themselves. In a sense, they create consumer-generated marketing just by being a good company to their customers, creating superior value (and new kinds of superior value) via their products.

None of this assumes a business operates ethically, of course, but from a theoretical point of view that is certainly the objective.