Last updated on August 15, 2013

Video Games, Art, and Objective Standards is an exhaustive look at video games, the ambiguities of art, and how they come to rest on objective standards – though maybe not in the way you were thinking. This series intends to show video games are a unique medium that deserves a special criteria and methodological examination. This is part and parcel of my theology as well. I invite you to leave comments on any section below!

- Introduction

- Preliminary Objections (2)

- (Preliminary Assumptions) Defining the Video Game

- Game Studies – Ludology

- Game Studies – Narratology

- Dewey – Understanding the “Live Creature”

- Dewey – Avoiding Abstractions

- Dewey – Video Games as Pragmatic Experiences (2)

- Judging Video Games as “Art” (2) (3)

- Addressing the Critics and Game Studies

- Conclusions

The video game, as a collaborative effort from both players and developers, allows both to participate in the creation of “an experience” within Dewey’s model. How do video games constitute “an experience” successfully?

Imagine the Church, for a moment, as a constant dialogue between God and man. God knows what He wants for mankind: to obey and serve Him. Man, naturally, rebels against this to his own detriment, as per his nature and temperament. God reacts accordingly by either, as in the Old Testament, setting up a Law to show mankind where to go rightly and wrongly, or in the New Testament, providing further supplementary material and fulfillment to what came before. It is, in a sense, a constant dialogue as God shows mercy and man chooses which way he will proceed, accordingly. We see in Matthew 16 that Christ establishes the Church with men, as a strange analog to establishing the nation of Israel:

13 Now when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, He was asking His disciples, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” 14 And they said, “Some say John the Baptist; and others, Elijah; but still others, Jeremiah, or one of the prophets.” 15 He *said to them, “But who do you say that I am?” 16 Simon Peter answered, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” 17 And Jesus said to him, “Blessed are you, Simon Barjona, because flesh and blood did not reveal this to you, but My Father who is in heaven. 18 I also say to you that you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build My church; and the gates of Hades will not overpower it. 19 I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatever you bind on earth shall have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall have been loosed in heaven.”

It is a covenant experience like the one that came before it. Peter confesses Jesus as the Christ, the Messiah, and this becomes a blueprint for all believers in the future. But now, God makes a covenant with all who will choose him, and not just those whom he chose (which is, paradoxically, everyone, if we look at Colossians 1:20). God communicates to us through a variety of sources, if we believe the whole history of the Church – Scripture, nature, reason, tradition all come into play, some becoming more authoritative than others. When you come down to it, though, theology is a very simple enterprise of give-and-take between God and ourselves. At least, that’s how I see it.

I seek to show God as accurate to the source I believe shows Him best – His Word. That is why I take Scripture seriously, and why I study it so scrupulously to avoid inserting my own wants and desires into the text. I do not take it lightly. Yet, I also try to make it practical, and not judgmental. It is a constant conflict between what I want to do, and what I don’t want to do as per a fallen nature; I imagine everyone who is a Christian feels similarly. Strangely enough, Dewey’s pragmatic experience concept fits right into this constant pushing and oulling.

Here, we enter into the criteria for video games that provide the kind of experience listed previously, and those that do not. Firstly, any game that hopes to fall under the category of immersion and “art” must involve conflict of some kind. Whether that conflict goes against some antagonist or even the fish in a fishing simulator, any video game creates an arbitrary set of goals that are, in fact, difficult to achieve. There is a struggle inherent in the enterprise, for without it we merely tread water. All the numbers going up and all the busywork clicking in the world can’t disguise an empty experience (I would point to Facebook Flash games, but I just did that! Whoops!). We need perceptive eyes to distinguish between that which fulfills and that which tickles our metaphorical artistic funny bone. Or, perhaps, distinguish what actually works in games versus what doesn’t. Art does not mean meaning by obfuscation, contrary to popular belief as such.

In recent years, games have been criticized for a lack of difficulty, in that game developers try to appeal to the lower common denominator for profit; Super Mario Galaxy, for example, repeatedly emphasizes concepts that the player has already learned through talking animals scattered throughout the game, just to ensure the player remembers. Rather than positive reinforcement through individual situations within the game, this patronizing approach is distracting to those intelligent enough to call various game mechanics to mind when presented with similar situations. Even then, there’s a right and a wrong way to enforce this trait.

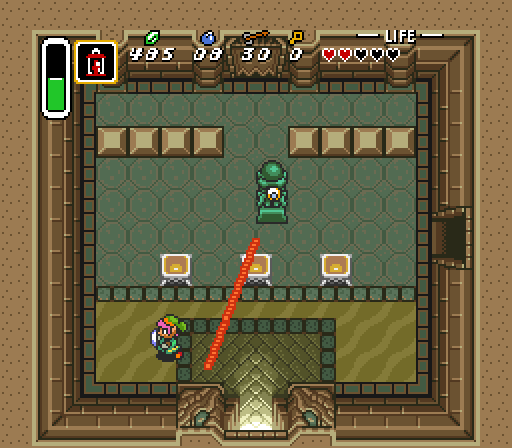

We could identify a similar problem in the traditional Zelda puzzle – four unlit lanterns appear in a room. You have a lamp. The solution is, in effect, a video game trope: light the four lanterns, and the door will magically open. Certainly, the game trains you in a particular mindset to solve its puzzles, but you will encounter this same sequence over and over again with little variation. The theme doesn’t reward anything but recalling a bit of knowledge derived previously; you are not actually solving a puzzle. You are merely identifying a pattern, a pattern that the developer wanted you to learn. You are not developing skills, or learning mechanics, but merely a rather strange way to open a door. I call this a strange moment of cognitive dissonance that removes you from the game.

Now, of course, we could justify this by saying Zelda isn’t a mechanistic universe and that is fairly well-established, but Zelda provides plenty of other ways to solve puzzles that make sense in mechanical terms and don’t usurp the tools on hand to learn silly patterns. I cite the “water levels” puzzle used in the Swamp Temple of A Link to the Past and the Water Temple of Ocarina of Time as good examples of this. A video game that provides “an experience” does not bombard the player with tutorials, written text or otherwise, as it distances the player from the video game’s intended immersion – in other words, it is inchoate. It lacks proper development, a proper curve. We don’t see this in real life, so why accept it in a video game?

I suppose that’s why I am so critical of games like Journey: I see potential, but little of worth, little that requires struggle and effort to maintain. The service of the Church isn’t easy, so why should I settle for less in video games? Fighting games require untold hours of practices and mental fortitude, let alone physical dexterity, to play at high levels; is there anything even close to that in the indie game scene? Too much credit-feeding, not enough depth. A pragmatic experience leaves its mark on an individual or community, while one that fails in this objective does not, becoming little more than an object of ridicule. It doesn’t mean someone cannot find themselves hoodwinked into liking a bad thing, or into hating something good, but that is also a Christian notion, no?

So it is that we must establish additional criteria in the next section for the notion of proper “pragmatic” experience.