Last updated on October 2, 2013

[list type=”arrow, square, plus, cross or check”]

- Part 1 – Materialism and the Role of Myth

- Part 2 – The Illusions of Choice

- Part 3

For children are innocent and love justice; while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.

– G.K. Chesterton, On Household Gods and Goblins

Our culture assumes that such great tales do not provide us with a real context for our lives. How many people look down upon the video game player. This guy will never grow up! Aren’t you a little too old to be playing games at your age? Join us in the real world and put your toys away. You cannot get anywhere with the way you live, now.

And thus the video gamer tries to justify his hobby, his passion in a myriad number of ways. Let us affirm, again and again, that the medium has “grown up”. Our narratives fit in line with the predominant paradigm of the day. Whatever the case, we must push those “childish” games away so that The Walking Dead becomes our new paragon of storytelling. We need to show the world that “art” can exist in a video game, whatever that means.

That’s all well and good, and I encourage and laud the diversity of video games. But they miss that taste for Fantasy and faerie-stories as a result. By arbitrarily choosing (perhaps subconsciously) to remove the “childish” face of our narrative – or at least the face we shoot off our foes – we relegate the origins of the genre to the sidelines. The stories of heroism turn to a bleak world of reality. Our heroes do not hold grand mystical weapons, but an endlessly customized gun. We slap the gaming world with a myopic fog, unable to see the benefits of the past and continually looking toward to the future. In other words, we call it “evolutionary progress”, more Nietzschean than Christian. But evolution towards what?

I understand this sentiment, I really do. Have you never tried to convince family, friends, and total stranger that video games provide something in your life that other hobbies simply do not? Has the Internet not shown us the depths of that connection, wherein a gigantic gaming subcultures exists for every genre and every type? We all seem to exist in highly isolated pockets, but technology allows a fuller communication. Yet, even with the advent of the availability (and, granted, popularity) of video games, they’re still lambasted as time wasters.

Every person feels this compulsion of societal pressure. The subtle coercion of culture promises the ability to “grow up” – but to what? To a life of endless anxieties? To a time where “this is how it is, and nothing else”? What delayed adolescent (the writer here is twenty five, all things considered) hasn’t seen that world and said “this is not how it should be”? Should the realm of video games need to evolve past the simple concept of a “game”?

You may wonder why I tend to enforce a strict definition for “game”, contrary to the ludologist or the narratologist. People throughout the ages played “games” with wide and varying rules and meanings. It is not because I do not think games can tell stories, or that wandering in a virtual leafy glade constitutes an “experience” – rather, I think such thoughts co-opt the video game form. Regardless of common usage, video games had a precise definition up until recently. New “indie” games and their ilk made a convoluted mess out of the project. They made games, surely, but some of them did not have the common boundaries of a classic video game.

Unfortunately, much as we could say that video games remain just like other games…well, they cannot exist in that realm by virtue of being “games”. Conceived as a set of rule systems, video games operate by the boundaries of the programmer and whatever results the developers set. They do not allow for boundless possibility, unlike a state of play or fun. Rather, they coerce the player into a specific kind of rule-based system. Some games convey their rules better than other, and even “no rules” can be a rule. To say otherwise highlights an absurdity in this bizarre definition-forming game: video games must have rules, whether by virtue of program or game-type.

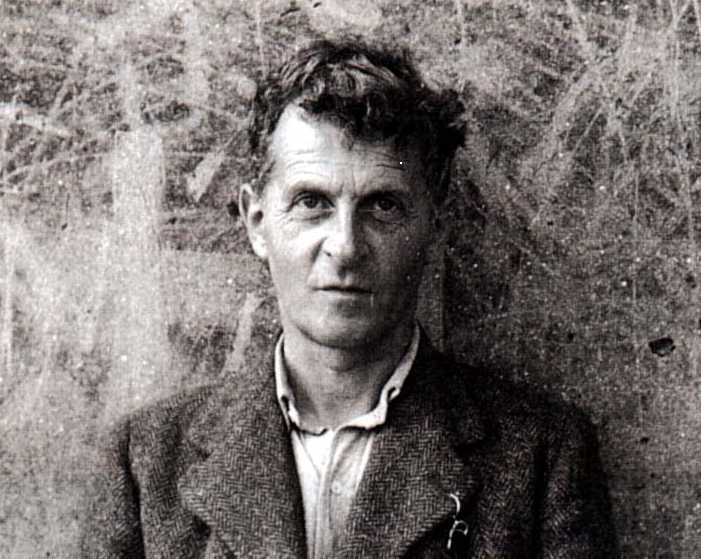

So, we see that video games, by definition, need rules of a kind. As much as I respect Wittgenstein’s views on language games, I must reject Philosophical Investigations on this point, Zombie W or no. A logical deduction from the use of a word does not affect the object in question any more than my using a particular bit of language affects you, the reader (if you so choose, anyway!). If, as a Christian, I believe in objective truth, I can’t accept language that works in that fashion either. When, for example, we have this pleothera of verses:

John 14:6a – Jesus said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father but through Me.”

1 John 5:20 – And we know that the Son of God has come, and has given us understanding so that we may know Him who is true; and we are in Him who is true, in His Son Jesus Christ. This is the true God and eternal life.

1 John 5:6 -This is the One who came by water and blood, Jesus Christ; not with the water only, but with the water and with the blood. It is the Spirit who testifies, because the Spirit is the truth.

Psalm 35:1 – Into Your hand I commit my spirit; you have ransomed me, O Lord, God of truth.

Isaiah 65:16 – Because he who is blessed in the earth Will be blessed by the God of truth; And he who swears in the earth will swear by the God of truth; because the former troubles are forgotten, and because they are hidden from My sight!

Who can say otherwise?

The intention of the author and his/her/God’s authorial control remains the important factor, not my personal experience. When they link together, I experience a personal meaning, but that does not mean that the wild and woolly world of “how I feel” and not “how I think” becomes the standard. Rather, the developer’s rules create the experience of the game outright. “Freedom” isn’t an option in a video game; I am not free to change the rules, nor make ones of my own. I work with whatever tools come to hand.

The games prior to the video game crash, simple though they appear, operated on simple sets of rules. Those rules grew more complex over time in every respect. The heart of the game, however, did not fade: rules exist. Clear, specific rules. Even if a tutorial does not convey it, or a game lets you discover the purpose on your own, a designer always has an intention with their video game. Even the independent game makers from thatgamecompany to PlatinumGames (if you disagree with PG as a “independent” developer, read this) should know this well. Both companies listed here have entirely different ends, yet the way they conveyed their game mechanics revolve around their intentions – not the player’s, regardless of how much we wish it otherwise. Dialogue trees and moral choice end in the decisions presented by the developer, not those chosen by the player; the prestige’s grand illusion simply lets the player feel as if they made a decision, when in fact they were guided to make a rules-based decision within the concept of the game.

But, our games enforce the illusion of choice as a grand mystery. One’s actions in a virtual world magical equate to those in the real world. That, to me, seems highly bizarre and almost absurd. Does a mix of polygons become a broken bleeding human body through some willful disbelief? Does Raiden’s cheery choppy choppy in Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance equate to a real-life ultraviolence? No, they do not.

Yet – and here is the important aspect of this conversation – they make us think or feel that we are doing these things. We understand that a game “plays”, yet find ourselves engrossed in whatever the game developer lays before us. Interactivity makes for a kind bedfellow with the stories of myth and legend precisely because, like a great bout of oral tradition or the rekindling of a long-lost, yet always present lesson, we interact in the process of its creation. We become part of the sub-creation of a sub-creation, a participant in a story. By that respect, the rules allow our participation even without the game’s explicit design for us in particular.

We call this, at the least, a preliminary reason for the use of video games and why they remain unique. They are not just for children; if anything, we know children as less mature and developed adults (not that this is bad, just true), but any truly successful game experience does not require an age barrier or unnecessary ‘adult” content. A child, certainly, entertains the notion of The Lord of the Rings as a real possibility, but an adult sees the same and feels just as impressed. It appeals to both audiences; to “dumb down” or “censor” the content for children means the original does not speak to all human beings equally, does it?

But they also show a critical error in the modern game design trends: they tend toward the realistic. They try to recreate a perceived “real world” – this is how it is – and then fail at it miserably. And why, you might ask? Because they’re based on rules, and if the world operated on such precise, linear rules, they would find instant success and instant connection among a vast swath of the public. But they don’t! These secondary worlds DO NOT reflect the real world; that is why they tend to fail.

Take Tolkien’s word: a successful sub-creator makes a world which reflects its own internal structure, but also says something about our own. If it does not, then it fails:

What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside. If you are obliged, by kindliness or circumstance, to stay, then disbelief must be suspended (or stifled), otherwise listening and looking would become intolerable. But this suspension of disbelief is a substitute for the genuine thing, a subterfuge we use when condescending to games or make-believe, or when trying (more or less willingly) to find what virtue we can in the work of an art that has for us failed.

The real world, as it were, works much easier than in a game because the concept doesn’t need the creation of a new world – only the acceptance of the current world in which we live. I find these terrible in their lack of creativity and completely lacking in that imaginative quality (excepting  Saints Row: The 3rd, as Joe would say). How many games lately capture what we’d call a true state of enchantment? Not many, I would imagine:

Saints Row: The 3rd, as Joe would say). How many games lately capture what we’d call a true state of enchantment? Not many, I would imagine:

A real enthusiast for cricket is in the enchanted state: Secondary Belief. I, when I watch a match, am on the lower level. I can achieve (more or less) willing suspension of disbelief, when I am held there and supported by some other motive that will keep away boredom: for instance, a wild, heraldic, preference for dark blue rather than light. This suspension of disbelief may thus be a somewhat tired, shabby, or sentimental state of mind, and so lean to the “adult.” I fancy it is often the state of adults in the presence of a fairy-story. They are held there and supported by sentiment (memories of childhood, or notions of what childhood ought to be like); they think they ought to like the tale. But if they really liked it, for itself, they would not have to suspend disbelief: they would believe—in this sense.

Although Tolkien restricts his discussion to stories in his particular wheelhouse of fantasy (and he says mean things about games, so bad Tolkien), we can equally apply this to video games. Every person in the game realm retains that one special game – regardless of its critical reception – that they love. Any number of circumstances could surround one’s play of the game, but it stays as an indelible memory in the heart. One will never forget it, even if they don’t play it again (though usually, the urge to return becomes too great to resist – hence the backlog). That sense of enchantment, I find, has been lost, and not due to nostalgia or the ravages of time; it was lost when the video game desired to “grow up” to…something. Like the teenager who must move out or run away, our gaming community still moves to and fro in its angsty phase without knowing what it wants to do with its life. It does not know its purpose, nor its objective, is a kind of desirability. Not wish fulfillment – that would be unduly harsh and perfunctory – but a wish that the world were different. And by different, we mean good, righteous, grand, amazing, extraordinary, and inspirational. That is what we lack:

Fairy-stories were plainly not primarily concerned with possibility, but with desirability. If they awakened desire, satisfying it while often whetting it unbearably, they succeeded.

In a phrase, “is it true?” is the question we all ask, adult and child alike.