Last updated on October 29, 2013

First, let’s talk about Max Payne 2’s mechanics.

Literally, there’s a host of minor improvements across the board. For one thing, the “enemies behind doors” syndrome and frequent booby-traps are non-existent. There’s a few cases where enemies will ambush you, but they’ll telegraph that particular action. Thus, your reflexes and skills are in control, not the whims of a sadistic level designer. It helps that the enemies are, in my book, a bit dumber than those of the first game. The dynamic difficulty adjustment actually works this time, as enemy can miss you when shooting – just like real life. Bizarrely enough, for a person like me who enjoys a stiff challenge, it’s quite a relief. Rather than create bionic mercenaries, Remedy Games takes the realism route by making headshots actually matter and rewarding the player’s accuracy.

Max’s skills in the way of the gun have increased as well. I rarely feel like I missed a shot due to the developer’s incompetence; most of them were entirely my fault for not having spatial awareness or for dodging completely wrong. Grenades and explosive devices actually harm enemies rather than make them shrug. Actually, explosions work exceedingly well due to proper usage of the Havoc physics engine, with bodies and objects flying all over the place in realistic fashion. Sometimes, you’ll see something more than a little wonky (like, for example, making an enemy fly accross the room simply by the strength of your bullets), but it’s incredibly fun to watch how firefights expand in the constant push and pull of bullets.Computer Gaming World described it as “a breathtaking, original ballet of death”, and while that descriptor shouldn’t fill you with awe nearly nine years later, the game’s graphical prowess still adds much to the overall experience.

Bullet time has also seen a number of improvements. First, adrenaline is self-regenerating. I failed to mention this earlier, but the original game only gives you the ability to use bullet time if you kill enemies. This made your effective use of bullet time paramount; any mistake could leave you without the one great advantage the developers give to you in their intense firefights. On the other hand, it can also be an exercise in frustration as you’re managing a resource required for most fire fights in the game. While this worked fine for shootdodging, the normal standing bullet time absorbs more adrenaline than it should, leaving you with little left. One bad autosave could be disastrous. Max Payne 2, like the modern game trope of the regenerating shield, gives the player additional bullet time if he/she waits patiently.

This wouldn’t work within the design of the original game, but it surely works here. Obviously, the more powerful bullet time was a design choice, and it makes firefights much more intense. Max Payne remains vulnerable, and still needs bullet time to survive; because of the improvements to bullet time, more enemies than ever before can be thrown at you in a single sequence, and this makes these actions setpieces incredibly satisfying. It encourages the player to walk into a room guns blazing, rather than the cautious play a lack of bullet time caused in the first game. Proper use of bullet time and shootdodging can prevent most, if not all, damage in most situations. A few cheap deaths remain, but it’s an overall improvement. It completely captures the feel of a John Woo movie in that sense; if the original game was “The Killer”, than Max Payne 2 holds the title “Hard Boiled” without question.

Secondly, bullet time while standing has gained additional benefits. First, Max Payne’s walk speed remains the same as out of bullet time. This wasn’t true in the first game, making standing bullet time entirely situation. Here, though, you can activate it, walk through a door and blast away a host of enemies quickly without wasting bullet time. The game also rewards you for chaining kills by slowing bullet time even more while increasing Max’s speed; it also allows him to reload in bullet time with zero time wasted, as time freezes. You can’t imagine how useful this becomes in the latter sections, where you’ll need every ounce of that bullet time to eke out a victory. The game, overall, is less difficult than the first game, but it’s for all the right reasons.

Every weapon has its use, contrary to the first. While conservation isn’t much of an issue, the game provides a variety of implements for the death dealer. Pistols work as low impact weapons, but they’re still useful; Desert Eagles still pack a punch, especially now that headshots work. Shotguns actually work in shootdodging now, and walking bullet time makes them incredibly useful for clearing a tiny room. Grenades and molotov cocktails can be equipped separate to main weapons, meaning you won’t have to fumble through your inventory to throw a grenade at a crucial moment. Just press the secondary fire button and you’re golden.

The level design, furthermore, also enchances the overall pacing. The first game drags towards the end because it goes for the 10-12 hour mark. Max Payne 2 tells a better tale with better action setpieces in 6-8 hours. Instead of a constant stream of thugs, Max Payne 2 gives such good variety throughout the game that I’m inclined to call it inspired. We’ve got the usual “underbelly of the city” locales, but also a high class apartment complex, a successful senator’s elaborate mansion, the RagnaRock nightclub (now renamed “Vodka”), a funhouse, and a construction site. Each of these contains some kind of action that differentiates itself from the other. In one sequence, you’re preventing Vinnie Gognitti, a crook from the first game, from exploding. Having been tricked by the main villain, Vladimir Lem, into putting on a CaptainBaseballBat Boy suit, he finds it’s armed with a bomb; it’s up to Payne to protect him.

Seriously, like real life, you can’t make this stuff up. Max Payne always had a sense of humor, and the sequel retains that tradition. Another set piece forces you to play Max’s love interest, Mona Sax, as she fights to protect him with a sniper rifle from above. You have to monitor Max’s health closely, as he can die if you’re bad at it. One sequence forces you to escape a fire; how many games do you know that force you to find a fire alarm? For a game with so much shooting in it, there’s many sequences where you’re not even allowed to shoot much of anything.

The main contributions of these sequences are actually relevant to the plot – that’s why they aren’t mere “levels” in the traditional sense. You’ll traverse whole levels without firing a single shot. One has you in a police station, tasked with speaking with a few people as the world continues without you. Even in linear sequences, you get the sense that there’s a world beyond Max Payne’s personal problems and conflicts. In fact, there’s tons of completely useless interactive elements for the player to discover, dialogue to hear, and places to find even within the context of this singular quest. It expands Payne’s universe beyond the singular focus on revenge and violence; there’s something going on here beyond the surface of “cool slo-motion gun fights”.

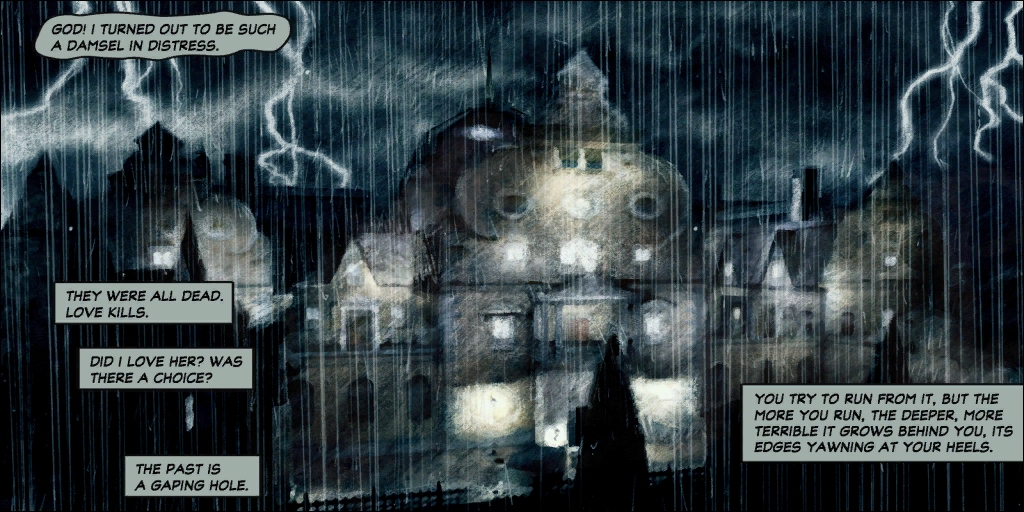

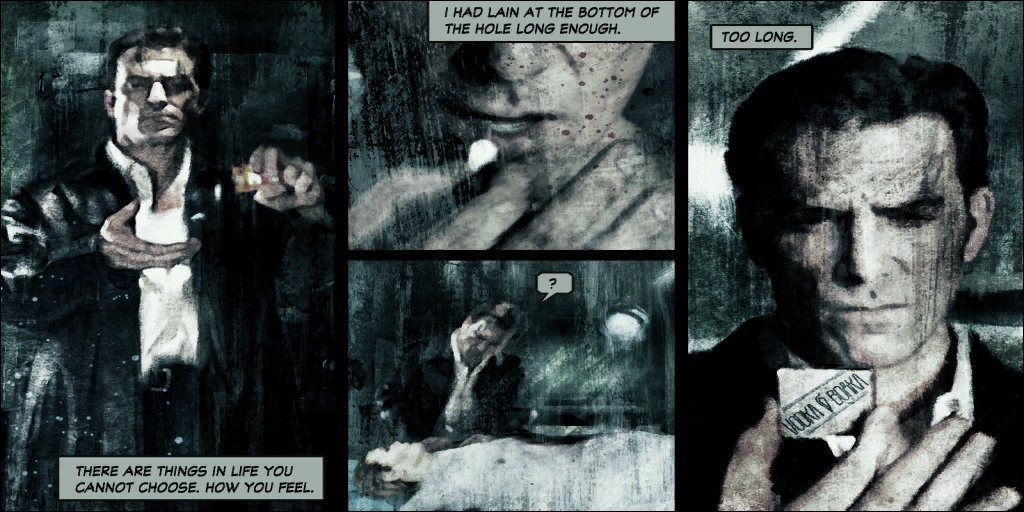

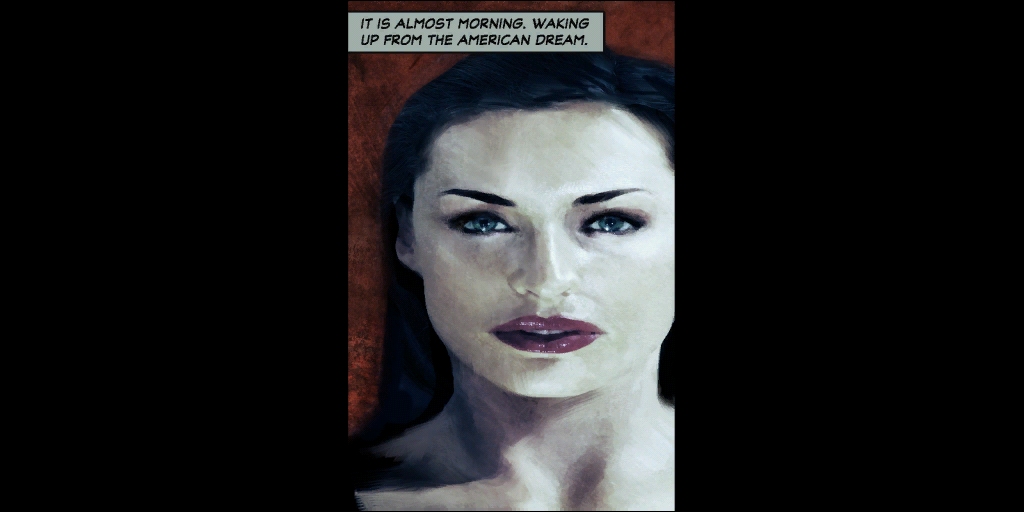

The hallucination/dream sequences exemplify this. Because they’re not caused by drugs with side effects of paranoia, they’re more like investigations into Payne’s psyche, the guilt he still feels over the death of his family, and even the guilt over the various people he’s killed (or believes he has killed) through the years. It’s this guilt, real or imagined, that keeps Max Payne in the world of stunted emotional growth and distance. It’s the past that keeps Payne from living in the present, and this central conflict plays itself out over and over again. The introduction says this better than I:

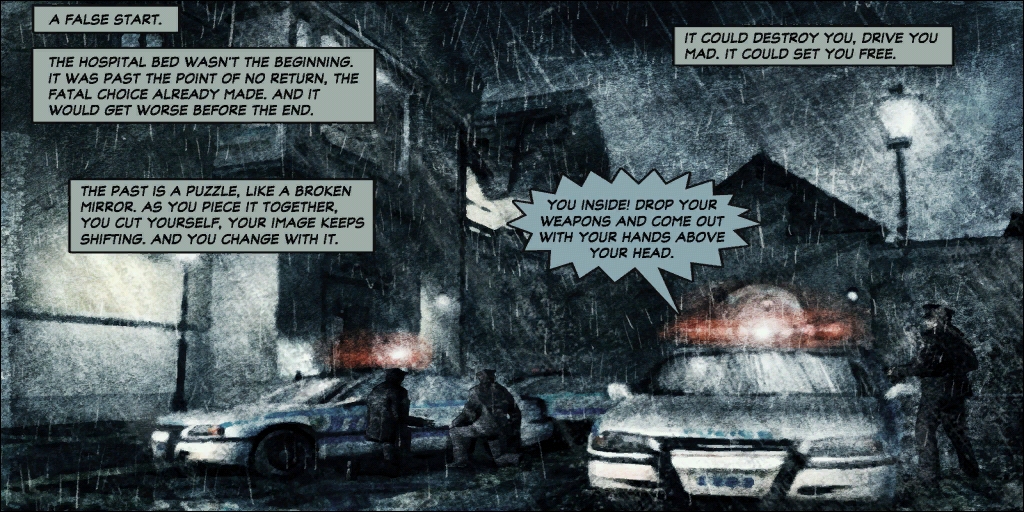

This sequence intends to mislead, but it sets the tone for the events to follow. There’s a hospital sequence in between which starts with quite a mystery: who did Max Payne kill? It’s not clear until the later acts that everyone has something to hide, including Max; it’s just that he’s more open with his own motivations than anyone else. A constant stream of inner monologue lets the player know what Max is thinking, what he’s hiding, and how he’s going to get out of this mess he’s found himself in once again.

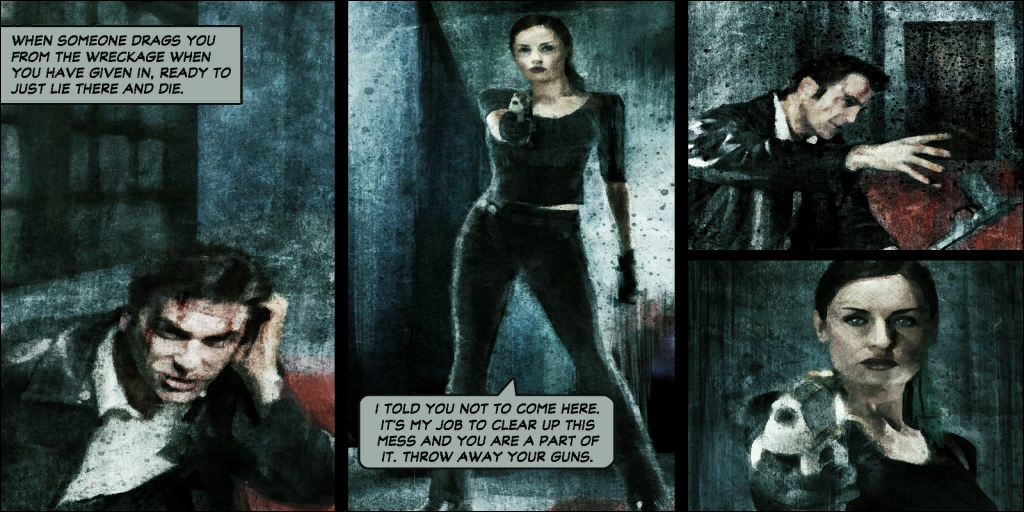

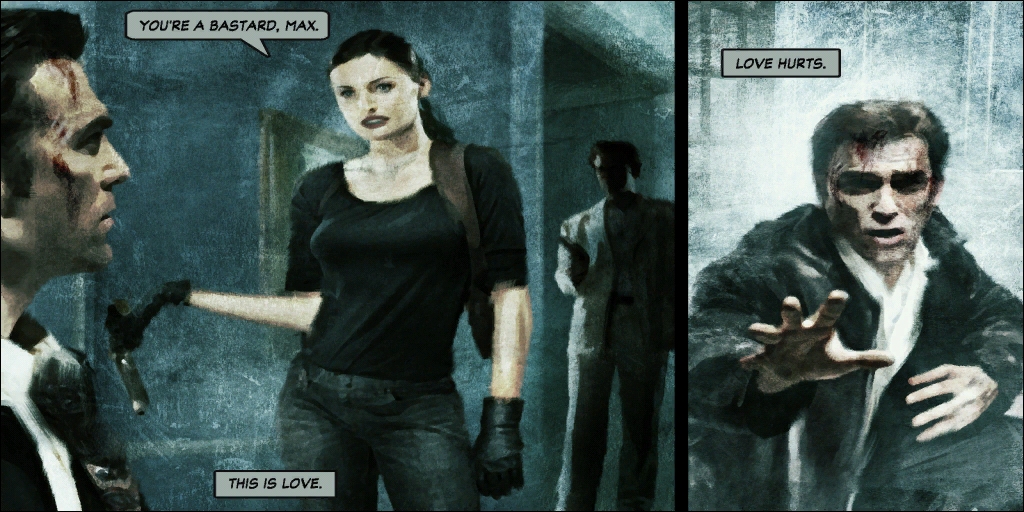

But the motive, here, isn’t vengeance – that period has already passed. Max Payne returns to the NYPD, disgusted with himself after his actions in the DEA. Woden’s influence may not have tarnished his reputation, but they certainly blemished his soul. Investigating a warehouse owned by an old “friend”, Vladimir Lem, he happens upon Mona Sax, long thought to be dead. In the first game, Mona Sax worked for the Punchinello family, and drugs Max but never hurts him. In fact, she sacrifices her life for him during Max’s assault on the Aesir building; she took a bullet to the head, but her body disappears from the scene. According to Max, her appearance triggers something within him, a lightning bolt that jostles him from his resignation and implores a search for answers. Was Nicole Horne really the only culprit? Who are these “Cleaners”, vicious mercenaries who are eliminating people of high power around town? Does Woden have something to do to this? It’s all a mystery, and one the player is happy to explore.

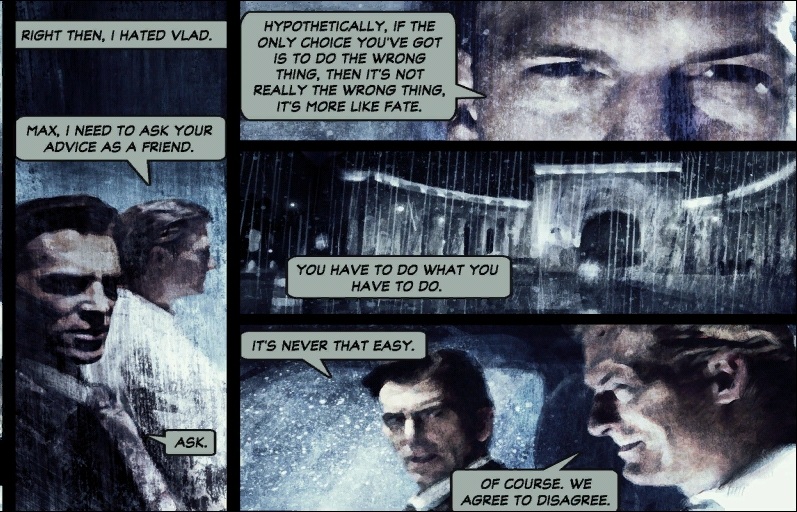

Even the cops who seem to follow the straight and narrow are corrupt. Even “friends” have hidden motivations. And even lovers work for someone you don’t suspect. The only person you can trust is no one, but Max is inexorably drawn to finish the story out. Woden was actually responsible for his wife’s death – the whole Inner Circle, in fact. Mona Sax works for Woden as well, and has the task of killing Max Payne when he becomes a “problem”. Vladimir kills all of the Inner Circle members to cement his own power, and kills Gognitti in the process. Payne can’t prevent the events he sets in motion; it’s fate, in other words:

Even Max’s walk through the funhouse gives us the same feeling:

When entertainment turns to a surreal reflection of your life, you’re a lucky man if you can laugh at the joke. Luck and I weren’t on speaking terms. Or maybe the place was just too lame to be funny. A funhouse is a linear sequence of scares. Take it or leave it is the only choice given. Makes you think about free will: have our choices been made for us because of who we are?

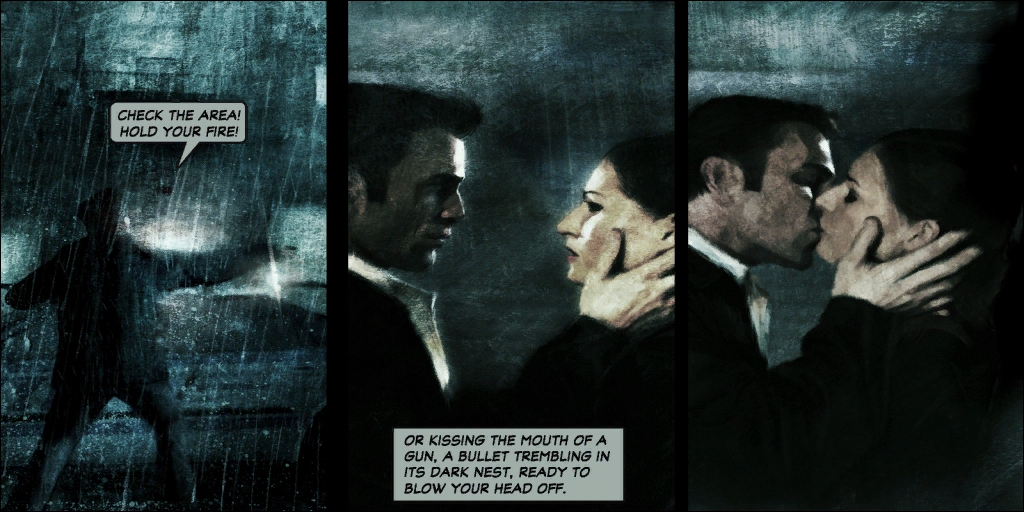

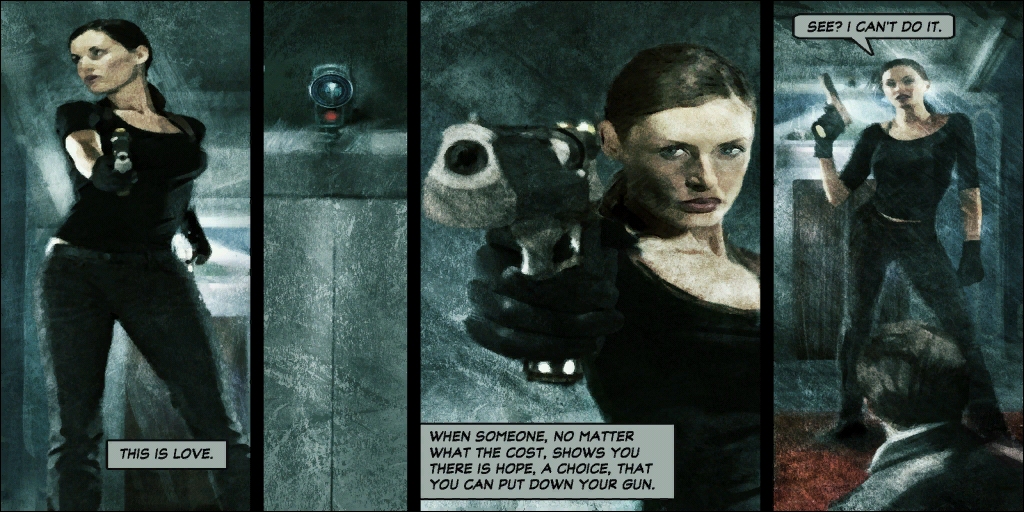

Max Payne 2 plays with the idea of fate through its course. This ties in directly with the subtitle of the game, “A Film Noir Love Story”; Max and Mona were destined to be together, however fleetingly. Max and Mona work as equal parts lovers and, bizarrely enough, a married couple. Although their attraction starts as eros, Max transcends these emotions as their relationship develops. They work together at various places in the game, and you even play as Mona for a few sections. Even though both know they’re hiding something, they continue to find each other in the darnedest places working together to finish the gang war Vladimir started. Of course, both lost something, or everything: Mona her sister and Max his family. They both have a gaping hole to fill in their hearts, and they are both drawn to each other as a result.

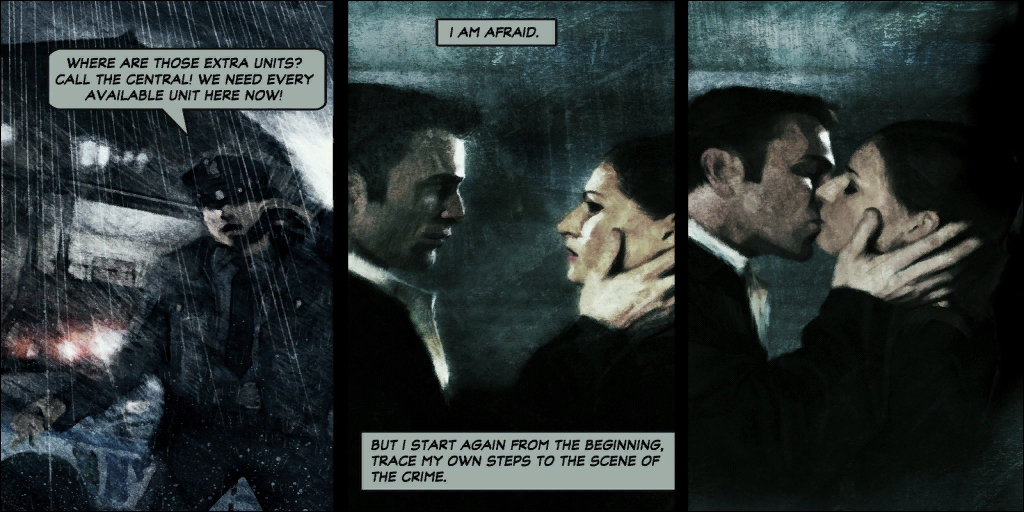

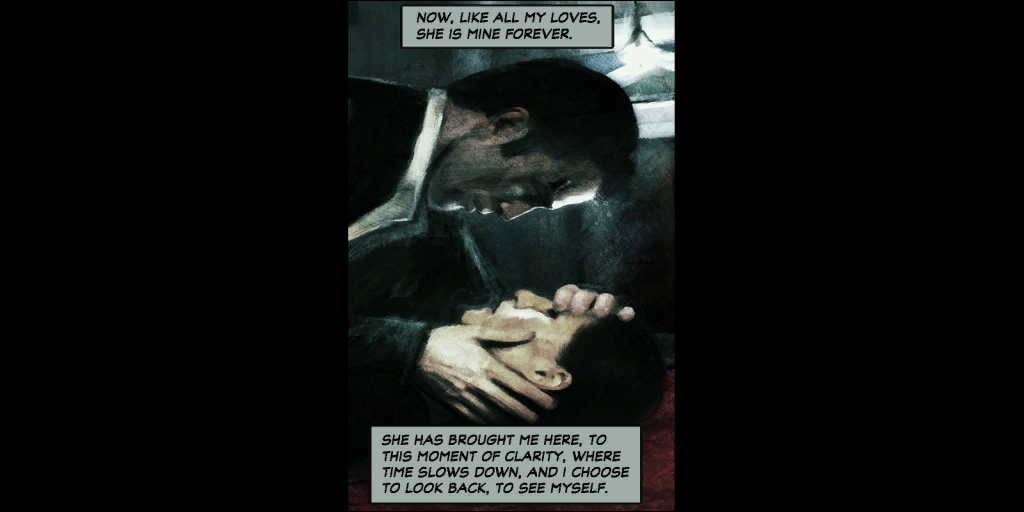

Max kills a cop to protect Mona; Mona saves Max from a fire and takes a bullet to defend him. There’s no reason why these nearly complete strangers, both adept at killing and getting themselves into trouble, should meet, but a wealth of common experiences says otherwise. The difference, here, is that their “love”, as we might call it, changes their perspective on fate. It’s no longer fate but their own free will to love each other that gives them the will to live. That is a choice; it’s not by chance that they are dealt these cards, but the choice they make in the here and now. Even if it’s fate, you’ll only be able to see it in retrospect. You have to deal with the hand you’re given. Payne says it best:

I was in trouble. I could only hope that Mona would find an opening with a view down to the yard to take out the Commandos out in time. Without Mona’s help, I’d be a dead man. Suddenly, for the first time in I don’t know how long, I realized, I didn’t wish to be dead.

When Max comes to in a hospital, he changes his tune:

It was time to fix things. And it is in trying to resolve these problems that Max begins to come back from his self-induced stupor. He begins to realize that emotions are, in fact, a good thing:

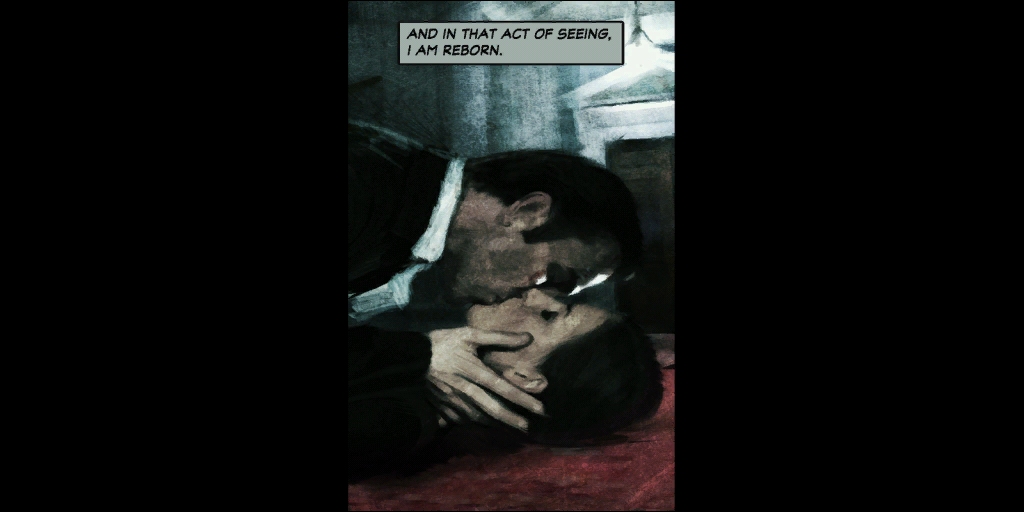

It is in finding this he gains clarity, the clarity needed to finally stop Vlad and end all this pain and suffering that originated with his own. It brings that old familiar feeling back, that of justice but gone right rather than wrong. There is justification in this violence; it makes sense. It isn’t a mad expression of anger and disgust at the world’s broken nature. Rather than sit by the sidelines and wait for things to happen, he takes initiative for the right reasons. It isn’t out of vengeance, or a violent deathwish; it’s out of love in the agape sense. Jesus says in John 15:

12 “This is My commandment, that you love one another, just as I have loved you. 13 Greater love has no one than this, that one lay down his life for his friends. 14 You are My friends if you do what I command you.

Certainly Jesus knows the value of self-sacrifice; he did it to save humanity on the cross. It is that truest expression of love from both parties. Mona may die, but Max will make sure her sacrifice isn’t in vain. I’m sure we could say that Max Payne 2 represents a version of the “redemptive violence” myth, but I don’t think it’s that simple. We’re presented with a world where the solutions were conscious choices made by all parties. They know what’s right, but they do what’s wrong anyway. That’s an interesting situation, much closer to the real world then we can understand ourselves. It can sometimes take a lighning bolt out of the blue to awaken us; even if we’re groggy and our vision is blurry, we are awake. We are conscious. And we have the ability to make the right decisions, even if they lead to the ultimate consequences. That’s love.

He finally moves on, and we the player cheer him along his path to redemption. It might be called “The Fall of Max Payne”, but he’s born again in the end.

Max cracks a smile; everyone’s dead, but all is right with the world, somehow. There are no happy endings, but there is resolution, Closure. And redemption. It’s such a different ending than what you’d expect – a man so focused on beating the world that he forgot how to live himself. It takes love to take him back from the brink. Even in the midst of violence, that’s a lesson anyone can take to heart.

That’s why Max Payne 2 still holds relevance to me today, and why it’s on The List.

(footnote: for fully voiced version of this stuff, go here.