Last updated on June 19, 2013

[list type=”arrow, square, plus, cross or check”]

- Part 1: “RPG Elements”, Metroid, and Personal History

- Part 2: A Retrospective on Pre-Symphony of the Night Castlevania

- Part 3: Why Is Symphony of the Night So Good?

- Part 4: Real-Life Vampirism and Alucard

[/list]

We could call Symphony of the Night (or Akumajou Dracula X: Nocturne in the Moonlight for you Japanophiles) an outlier from its progenitors. The series that spawned it never bothered with the Metroid franchises’s brand of slow-paced exploratory action; instead, Castlevania’s better known for its precise controls, difficult yet eminently conquerable stages, memorable setpieces and bosses, and that most glorious of video games weapons – the whip. The endless battle of the vampire-hunting Belmont clan inspired many yells of inspiration and victory, and just as many cries of curses and broken controllers.

The real appeal of Castlevania’s early years came from its unrelenting challenges and need for both skilled play and strategy. Levels felt like puzzle pieces waiting to be solved. Since Simon Belmont’s jump arc did not allow for course correction in mid-air (probably stolen outright from Capcom’s Ghosts n’ Ghouls series), you needed to make quite a commitment when jumping over a chasm. Could an enemy spawn when I jump? Could I attack them in midair, or would I plumment to my doom? Stairs, which you needed to walk up, also presented this same problem. Enemy configurations took full advantage of the stage’s composition to kill you. Every encounter became a duel to the death, and your wits and skill would bring you to victory.

However, preparing in advance meant you could traverse obstacles easily if you paid attention. Although Simon only used a whip which lashed straight ahead, Castlevania’s famous sub-weapon system allowed for multiple angles of attacks. Thrown axes worked on an arc, while holy water placed devastating fire on the ground, and holy crosses worked just like boomerangs (one of the more useful ones for most situations). Players could memorize the levels over time and develop strategies for when they knew a particular obstacles would appear, and where specific subweapons would drop. The same goes for the (in)famous “wall chicken”, health powerups that appeared in…well, walls when struck with the whip. Castlevania always encourages explorations down a linear path, and experimentation with all the tools at your disposal. Failure to adapt meant death, and it remains a harsh law.

While Castlevania’s difficulty remains in the public consciousness, it’s not that hard. Probably due to the fact that Konami’s new franchise arrived first on consoles (unless you call Haunted Castle a Castlevania game, in which case I don’t understand how your mind works), it’s rather forgiving. Lose all your lives, and you merely begin at the stage which you reached. There’s no password system, but (like all consoles) you could just leave your NES on if you wanted. Continual plays meant you’d keep learning with enough persistence but that’s how arcade games and video game in general operated at this time period.

Of course, the distinctive visual style and musical touches also enhanced the experience. Seriously, do you not know a Castlevania tune? Allow me to jog your memory:

The whole thing (though quite short) still reminds me of all those trying times working my way through the castle of Dracula. It’s both rocking and haunting at the same time, and nearly every track on the Castlevania soundtrack does this amazingly well. They’ve been remixed time and again, and it’s quite a testament to their longevity in the popular consciousness. Perhaps the supernatural/monster movie theming also helped a bit; fighting the Mummy, or Frankenstein’s Monster, or Dracula created the first “horror” game, so to speak. At the same time it embraced popular culture, it also brought an element of fear and dread in the mechanics. The game’s visuals and choice of setting simply added to the effect. A horror and skill-based video games hadn’t been done; leave it to Konami, masters of the arcades to come up with something special. You ascended the dark castle, overcoming obstacle after obstacle to take on the Lord of Darkness, and you could win with enough skill and determination. Trust me, it’s quite a rush. And Gothic-styled chiptune music adds to the atmosphere and flavor!

The other wonderful thing regarding Castlevania comes from its lack of consistency. So yes, there’s B-movie monsters and mythical creatures all over this game. It works well regardless, though! Video games, in their prime, became wonderful exposes of the bizarre and wonderful; worlds came into being solely out of the needs for mechanical consistency, player conveyance and recognition, or simply because the developers thought something looked awesome. You can’t blame them; development teams always make better games when they’d play it themselves. It makes no sense why this motley menageries of “scary” monsters would all appear in one game except for this reason! That schlockfest feel always made Castlevania special in my mind, the exact opposite of Metroid!

It shows a complete and utter disdain for its source material, and a lack of care for whatever tropes they copied to make their own thing. Hence, why Castlevania turned out so wonderful.

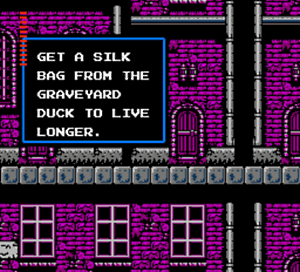

Still, the original game nearly perfected the design; what else could Konami do but make sequels after its success? Like most sophomore efforts from companies other than Capcom, they had mixed success. Most people lament the release of Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest. It tried, in its own completely haphazard and unsuccessful way, to turn Castlevania into Zelda. You looked for clues, you search around for items and abilities (or the money to buy them). Unfortunately for the West, the game was hampered with a terrible translation that made most of said clues and intuitive wordplay in the Japanese version an utter mess. I mean, who came up with the idea of crouching near a wall for ten seconds with a special item to wait for a tornado to take you away? That doesn’t make any sense, does it? Nor did the actual game, whose confusing color schemes and bad platforming really made it unplayable without a guide in today’s world.

Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse returned the series to its linear and challenging roots with the addition of multiple characters. Branching paths meant each playthrough would allow Simon to recruit new helpers such as Grant the thief, Sypha the magician, and Alucard, Dracula’s son. It doesn’t do much more than refining the formula of Castlevania’s first foray in both aesthetics and music. I could also say the same of Rondo of Blood, the PC Engine CD exclusive that everyone babbled about back in the day. It brought CD quality music and unbelievable animated graphics while still retaining Castlevania III’s branching paths and multiple endings. As well, it’s got the most perfect situational compound videofriction in a video game that Tim Rogers can imagine, so there’s that!

And I guess they also remade the original (Super Castlevania IV) too! It wasn’t all that great though. It lacked a certain something. After perfecting this wonderful blend of action and strategy, Konami couldn’t think of anything else to do with the series, all said. They released a few portable versions (all of which you should not, under any circumstance, play for fun) and one really bizarre Genesis game (Bloodlines) that doesn’t actually play much like a Castlevania game, but still retains the schlock in droves (so yes, it’s good).

As well, they released a truncated and relatively bad port of Rondo to the SNES, which no one likes because it’s pretty terrible. So the last game in the series circa 1995 was a lousy port of a wonderful game – not exactly a swan song. In any event, the series needed a kickstart, a boost, and a revitalization. Obviously, the fundamentals were sound, but what could bring Castlevania into the new era?

Of course, we mean the era of the 32-bit; Japan already had the Sega Saturn and the Sony Playstation vying for dominance with the new fangled, and now hilariously ugly, polygonal graphics of the time. Where could Castlevania fit into this mold? Either it would make the transition to 3D or use the new technology to boost its 2D graphics to new heights and new ideas. One wondered where they would take Castlevania, in all honesty.

How about a spin-off? Those always work!

So it was that they gave the Castlevania series to young producer Koji Igarashi. They handed him a multi-million dollar franchise, and told him “run with it”. He could break any rule and taboo of the series as long as it retained certain aesthetic and stylistic features. Here’s something you would never see in the video game industry today: handing an unknown director a gigantic project with little-to-no guidance at all. Well, I suppose he came into prominence with the release of the dating simulation Tokimeki Memorial, but that wasn’t something familiar to the West in 1997.

Apparently, Igarashi wanted to give the series more replay value and make the nonexistent “story-line” more consistent. In his words:

At the time the series was developed in a very scattered way, by various different groups, and nobody had overarching control of it from a top level. Because of this, there were many different storylines and conflicting timelines. I tried my best to integrate them, so as not to confuse the consumer. The first Castlevania I worked on was Symphony of the Night, and there I tried to clean up the timeline.

Honestly, I’m not sure what he means here. Certainly, Symphony of the Night actually exists as a direct sequel to Rondo of Blood (yes, a game unreleased in the United States for more than a decade after SOTN’s release), and the “story” barely exists in the game at all except through horrible voice acting and a couple overlays of written text. So what happened? I’m going to make a conjecture and say that IGA wanted to retain that Castlevania feeling while also taking elements from previous games in the series. If Simon’s Quest wasn’t a major influence, I’d feel baffled; Rondo of Blood obviously inspired much of the plot and graphical style (borrowed sprites, anyone), and the game borrows quite a bit from the Metroid series.

In fact, I’d go so far to say that Symphony of the Night appears a happy accident of time, place, influence, and just plain magic and/or circumstance. It’s that perfect combination of the last gasp of a two dimensional zeitgeist, and I don’t think we’ll see anything like it again, from IGA or otherwise.

Why do I say this? Well…