- Part 1 – Origins and Buddhism

- Part 2 – Neon Genesis Evangelion

- Part 3 – Hideaki Anno and The Culture Gap

- Part 4 – Final Fantasy and Psychological Deception

Today, we’re going to examine a different religion than our usual Christian focus. Specifically, that’s because I wanted to understand why people don’t like Japanese game stories, or even the design of the games themselves. I’ve never had much of a problem with it due to it being part of my childhood, but a lot of people throw their cultural baggage on the doorstep and expect Japan to magically comply with their demands for Western norms. Not gonna happen, folks! If there’s anything that reeks of intolerance in video games, this is probably it.

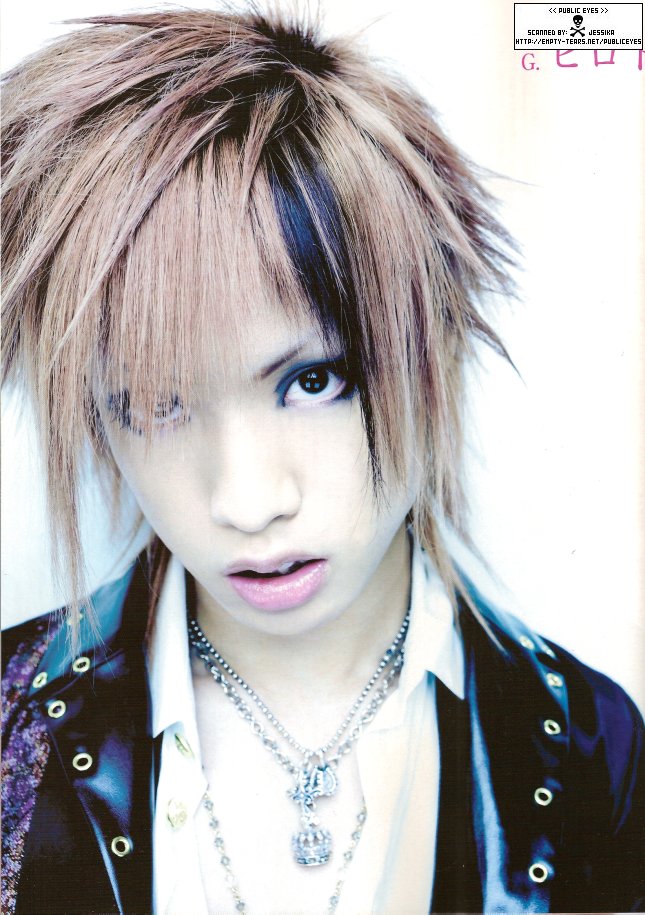

So this picture should show that the look of the games isn’t that unprecedented; it’s a cultural ideal with the youth of the country. I’ve noticed that many people characterize that peculiarly anime style, filled angst and melodrama, as “emo”. Our culture usually tags people with this label when they fit into a particular style – for example, emo as a genre of music, or even as a style of dress. Sometimes we use it in jest, referring to people who, perhaps, take themselves a little too seriously. In any event, having crazy Japanese hair or being a JRPG character inevitably leads to a characterization as “emo” from a Western perspective.

My upbringing meant that I did not know the difference between a proper “Western” literary narrative and a Japanese video game product – I grew up with the latter, and so the former came as a surprise. Maybe elaborate melodrama or deliberation about world-saving didn’t always come into play. I always felt that appeared integral to the plots, as saving the world never felt like an innocuous or easy task. Their questioning justified their actions, and while it broke that Western story trope “show, don’t tell”, that’s how they always told it.

It happened from game to game, without fail, as if someone foisted success upon that particular style and everyone else copied it by default. While I understand that Japanese society heralds community and (to a degree, and in public) conformity, this also applies to business ventures – what works, works, and why not keep doing it? We can accuse them all we like of lacking “innovation”, yet people continue to buy them. If there wasn’t an audience, then they wouldn’t keep making them; the mainstream press is the audience that doesn’t like them, not the people that continue to purchase them.

So the question, then, is: why? I think I’ve got a good idea, but you’ll need to wait for this huge, long preface. To summarize in one phrase: Neon Genesis Evangelion. Of course, a secondary element comes from a completely different religious heritage that grasps very different ideas. We tend to think of life as a story or narrative, and that probably comes from our common Christian heritage. Christianity’s a story, after all, if a particularly true one that impinges on the way we live. In the same light, Buddhism affects how Japanese games come to being and what themes they display. Eastern religions do not restrict their beliefs in the same way; they absorb influences from all over the place, usually resulting in borrowed practices (what academics would call “syncretism”).

Whereas we see these mixtures as “inconsistent”, “wrong”, or “heretical”, they see them as pieces of different truths. They learn from other religions and add it to their own. This happened in the working of early Japanese Christianity, which continued to function even after being outlawed sometime during the Tokugawa Shogunate. They adopted Shinto and Buddhist practices into their Christian rituals, and missionaries from the West found this equally frustrating and fascinating. How could they believe that Jesus Christ was Lord, but also adopt worship of nature spirits (who they thought fit under that god in a pantheistic sort of way)? These are difficult questions, especially when the alternative requires a theological explanation.

Still, imagine the history of video games without this background, and it would look pretty empty. Just about every fantasy game from Japan retains some religious syncretism in there, or at least borrows names and symbolism from different world religions. Most summoned monsters in Final Fantasy, for example, come from one religion or another (Shiva and Ifrit from Hinduism, to cite a common one), and Shin Megami Tensei levels the playing field by throwing every religion in the mix as an equal party. Dragon Quest is the only RPG I can imagine that plays its whole notion of religion straight, as does Castlevania, but both became rather milquetoast with Western localization. It’s strange to think that their creativity came from their willingness to tamper and shift notions of religious belief into video games.

Because of this, I’m reticent to accuse them of intentional offense, or even “bad” storytelling, precisely because all of it comes from an amalgamation of different culture influences reinterpreted in a uniquely Japanese way. What looks like a horribly constructed narrative to our well-known Western literary mind actually resonates with that audience. And, sometimes, with myself, otherwise I wouldn’t continue to play these games AND enjoy their stories when necessary. Of course, this only really applies to games that actually have a story, so keep this in mind.

I am also NOT arguing for the superiority of culture, here. I do think Christianity exists as the one true religion (in both the Western rationalist sense and in the sense that it corresponds with reality), but that does not mean MY cultural paradigm suddenly subsumes all others underneath its boot heel. Some cultural notions translate well from place to place, and others do not as their culture continues to grow towards different values and different meanings. I would argue that happened right here. Let us start at the root of the whole thing, with the “Japanimation” craze that all the kids were into during the 1990s.

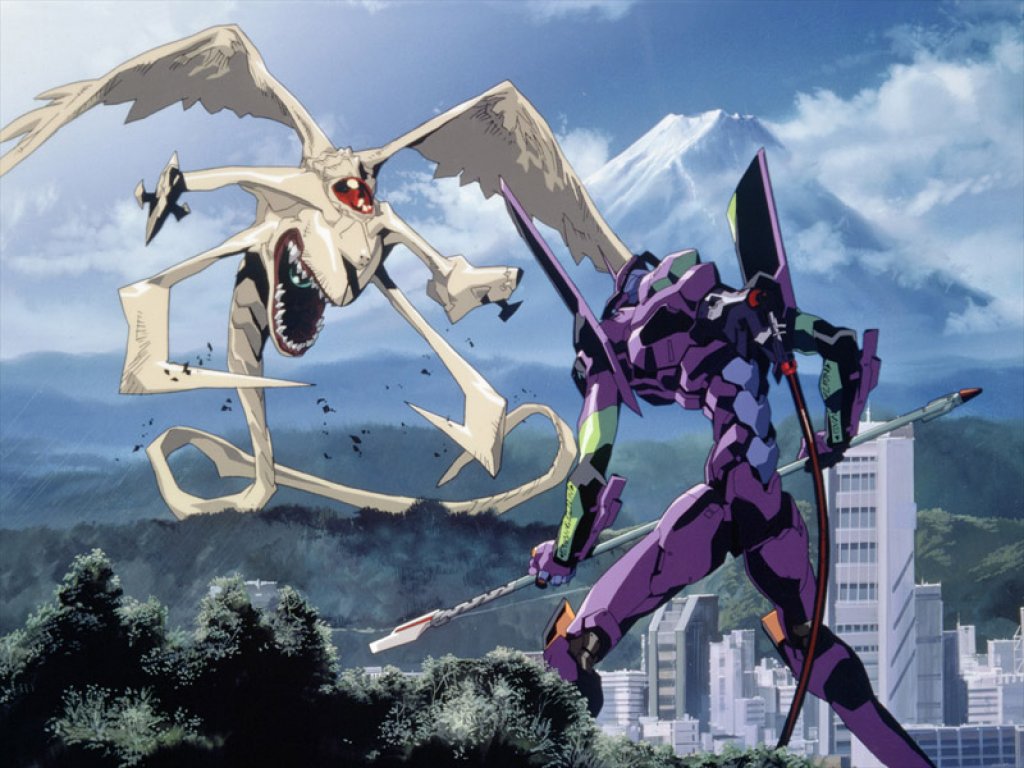

In any event, we need to discuss Neon Genesis Evangelion if we hope to understand why modern JRPGs continue to place an “emo” protagonist/party in their games. As one of the most influential anime series of all time, its impact on Japanese pop culture cannot be underestimated. Since its debut in 1995, its striking visuals have become standard in the anime industry; in fact, it caused a revival of the giant robot fascination in Japanese culture. However, what Evangelion left a legacy and a new approach to story telling. In what could only be described as a postmodern apocalypse, director Hideaki Anno integrated various religions, philosophies, and the human experience into a polymorph that brought about fierce debate over the series’ true meaning.. However, regardless of this complexity, fans embraced the series as a true innovator in storytelling within the context of animation.

One element stand outs as incredibly important in Evangelion – Buddhism. Evangelion‘s plot revolves heavily around the concepts of Buddhism, such as suffering, enlightenment, and the cycle of rebirth. These concepts, however, are taken out of their original context and applied to a real human in a different universe – Shinji Ikari, the protagonist of the series. Through him, the viewer sees his path through the suffering of the transient world until his eventual realizations at the end of the series that, quite literally, shape the foundations of the world in which he resides. Certainly, Buddhism may be difficult to decipher through the heavy syncretism applied liberally throughout the series (no surprise there). As much as Evangelion plays out like a new apocalypse story with an unlikely savior figure, Buddhism remains integral to truly understand the messages conveyed. The syncretism of Buddhism flows from practical application in Japanese life to art within Evangelion.