Last updated on March 4, 2013

I realize that’s from the soundtrack box, but it’s the best logo I could find. I own the box, anyway, so why not?

The SaGa series, made by Square-Enix, is a weird anomaly in their catalogue, something of an unwanted stepchild or ugly duckling. Helmed by Akitoshi Kawazu, it has seen extreme popularity in the East (9,9 million copies can’t be ignored) – and utter disdain and hatred in the West by most mainstream gaming publications. Why is this? Let me note a few things about SaGa:

1. Almost all of them are set in the traditional European-Fantasy setting that most American fantasy games would herald as their particular context. Certainly, the art-style always remains uniquely Japanese, but it’s not as if SaGa games move from those tropes too far to be unrecognizable.

2. It’s a Square game! Everybody like RPGs, right? Well, console gamers like RPGs from Japan, anyway. Shouldn’t it play just like Final Fantasy? Battle systems, awesome story, yes!

3. The music, by a variety of composers (notably Kenji Ito and Masazhi Hamazau, who’s name should be familiar in regards to FFXIII) is absolutely wonderful, and captures that sense of adventure and whimsy that so many Western RPGs fail to grasp.

All of these elements would seem, to any observer, like a total home-run, a smash hit, and a sure thing. I can tell you one thing: it should, but it doesn’t.

If anything, SaGa was ahead of its time in terms of localization to the West. It does exactly the opposite of the linear, story-based game, relying more so on the conventions of CRPGs and Dungeon & Dragons with its open-ended progression and lack of direction than on anything Square usually produces. It does have a plot, but the narrative unfolds in a freeform manner, dictated by actions and quests taken throughout the game. As such, this gives the player a framework to explore the world of SaGa, rather than adhere to some set format.

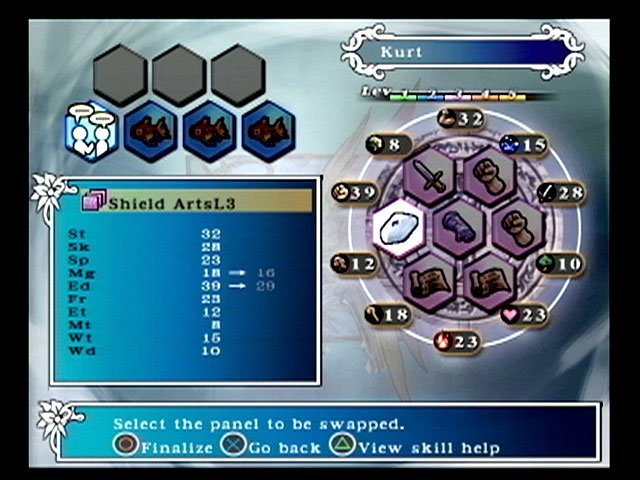

However, non-linearity would seem like a grand innovation if not for the game’s mechanics, which tend to sour most people’s outlook on these games. In a nutshell, SaGa games present bizarre, un-intuitive battle mechanics to the player. Kawazu, as director of Final Fantasy II, implemented a system in that game which awarded strength to particular statistics depending on what you did the most in fights. Are you smacking enemies with a weapon? Your strength will increase. Using healing magic? Your skill at this will increase. By injecting elements of real experience, it certainly appeals to our sensibilities on paper, but in practice you can easily break the game, or it can break you. Hit points can be gained in massive amounts by letting enemies wail on you, or killing each other as a weak enemy is left alive solely for leveling purposes. Furthermore, without knowing this is how the experience system works, you could arrive at certain points in the game with a totally unsuitable team, forcing you to restart or spend many, many more hours grinding. It’s a tedious exercise, to be sure, but there’s some delight to be found in exploiting system mechanics – Tri-Ace’s earlier games take this same trend, yet they have not been reviled for their freedom in mechanics.

SaGa was the moment when Square gave Kawazu his own studio. You can tell how that went over with some people. And especially when Square’s U.S. releases of the games had the gall to call themselves “Final Fantasy Adventure”, you were really getting hoodwinked into playing an entirely different game series. As such, it’s probably the only series of games that has ever led me into utter confusion and frustration. When I bought the first one for the Game Boy, it was not at all like the Final Fantasy I had played. Why do we have three or four different races to choose for our party? What’s the difference between humans, mutants, and monsters? How many should I have? Why do all the weapons have durability/use points? Where am I supposed to go?

The games, most of which were never, ever destined for localization, continued in this vein of an open-ended world, but simply, absolutely confusing mechanics and convoluted play systems that don’t make any sense unless you actually go and research this stuff for hours. I’m going to guess most gamers aren’t willing to spend the time for a lot of these games. They do, at points, change things just for the sake of being different, but I think there are merits to SaGa. Unlimited Saga, especially, basically killed off the series in the West, allowing only a remake of Romancing SaGa to be localized before Square-Enix pulled the plug for the Western market. Remakes continue to be made and sold in Japan exclusively.

SaGa, then, hearkens back to a time when game were just games, and since no one knew exactly how to treat video games differently, we had what are called “instruction manuals”. Usually, these are now just a selling point (FULL COLOR MANUAL, ATLUS IS THE BEST), but they formerly contained actual information about how to play a game – baffling, I know. Of course, SaGa takes this one step further by making sure the manual tells you how battles work, but not quite everything. Exploration is the key theme, not just in the world design, and I appreciate a developer thinking I’m smart enough to figure out something on my own rather than plastering a tutorial into my face. Whereas Elder Scrolls games, for example, pretty much boil down the combat to “smack it or cast something on it”, Romancing SaGa mashes turn-based combat with all sorts of weird variables and random level ups (yep, not traditional at all), or even dice rolls. It’s up to the player to deal with changing circumstance through skill, whether winning or losing, by making good decisions with the tools at hand. Of course, you can die randomly due to being dealt a bad hand, but it’s all part of the experience – save often, in other words. Plus, you can’t see everything in one playthrough (at least later games in the series), so there’s incentive to replay it again after mastering the system for new challenges. As well, the “plots” played more as a series of interconnected vignettes, all of which represented a part of the greater SaGa to save the world (hence the name). This gives a very different feel when you’re describing a “story” – it piles on the little details about your band of heroes, whoever you chose as party members, and thus every play-through ends up as a unique experience.

SaGa won’t ever win awards, or be well liked by the public at large because of these divers complications and sometimes completely arbitrary mechanics, but I suppose that’s not that important if the game is fun for someone. One man’s poor design is another man’s journey to discovery.

Perhaps cultural difference might account for it, rather than taste. Allow a theologian a speculative conjecture about SaGa’s lack of popularity in my native home: our culture has evolved to a different standard of work and effort than, let’s say, Japan’s overly-enthusiatic (and socially expected) work ethic. I am not saying it is superior; they work too much, and we work too little; both have their own problems. In the land of plenty, much has been given to us on a silver platter, and we’ve grown accustomed to such through pretty much the whole of society. Failure, if that’s even a word anymore, doesn’t exist – Facebook doesn’t have a dislike button, after all, for we may hurt someone’s feelings.

Feelings have become the main criteria for everything, rather than thoughts. Western video games, as well, have taken to monitoring the feelings of their players – take the recent Mass Effect 3 ending debacle, wherein many gamers found themselves entirely dissatisfied with the artistic direction of ME3’s finale, which gave little information as to what happens. The fervor reached such a fever pitch that BioWare, sacrificing their own artistic integrity, basically gave in to fan demand and produced new DLC explaining, adding, and changing elements in an attempt to appease the fans. As far as video games becoming the next medium of “art”, having your viewers decide what’s good and what’s bad solely by majority rule might not be the right path.

The armchair philosopher of “video games”, the fratboy on the couch, feels particularly slighted and voices his altogether “important” opinion on some internet forum, and by golly he’s being heard. “Give me a tutorial”, he says – I hate reading too much. “Make the game simpler” – I hate having to learn all these controls. “Tell me how to play, and where to go”, he says – make sure I don’t get lost. “Auto-save repeatedly so I don’t lose my spot” – I have a life, you know. That is, video games tailor themselves to the player, not the other way around.

A time did exist, however, where people earned respect, and weren’t merely given a place because of their feelings, but their ideas. They did something, rather than look from the benches towards the producers in society. 2 Thessalonians 3 contains the infamous “apostolic mandate”, which was the basis of American society up until LBJ’s Great Society:

6 Now we command you, brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep away from every brother who leads an unruly life and not according to the tradition which you received from us. 7 For you yourselves know how you ought to follow our example, because we did not act in an undisciplined manner among you, 8 nor did we eat anyone’s bread without paying for it, but with labor and hardship we kept working night and day so that we would not be a burden to any of you; 9 not because we do not have the right to this, but in order to offer ourselves as a model for you, so that you would follow our example. 10 For even when we were with you, we used to give you this order: if anyone is not willing to work, then he is not to eat, either. 11 For we hear that some among you are leading an undisciplined life, doing no work at all, but acting like busybodies. 12 Now such persons we command and exhort in the Lord Jesus Christ to work in quiet fashion and eat their own bread. 13 But as for you, brethren, do not grow weary of doing good.

It was understood by the early Church that a person never should rely on the kindness of others unless absolutely necessary, that he/she must be self-sustaining, for the poor could not be helped if Christians were poor themselves! The accumulation of goods was a vehicle for a greater cause, not an end in itself. Imagine that American charities used to require a man, whatever his economic position (with obvious exceptions), to chop wood for several hours straight. This was to test his dedication to the task for receiving care, that he was willing to work his own way out of poverty and not to rely on the charity of others for his own personal gain. The situation has changed greatly since then, and our games (now developing a Western focus, considering the overwhelming state of the American market) have changed along with it.

A nation of busybodies can’t sit down to play a game like SaGa. It’s too complex, too rich an integrative tapestry of disparate parts that encompass a greater whole. There’s lots and lots of interesting and fascinating mechanics, but who has time, right? We take, but we don’t make and give in return. Games of the past took this to heart; they expected something of a player. They expected your dedication and your attention, and if you weren’t willing to give it, then you weren’t going to win or obtain any satisfaction. That’s what inspires the challenge to conquer and succeed at the game, rather than handing you the victory and yelling “what’s next”? We don’t want to work; we want to win without trying, and lose without consequence.

This isn’t meant to denigrate anyone in particular or to make a political statement – I feel this impulse as much as anyone to be lazy and slothful even when I know I should be doing something real. I worry that the degeneration of culture has reduced our attention spans, and thus our ability to appreciate certain things. Some activities take more effort and time then we’re willing to give, like SaGa games. That has to change.