Last updated on March 26, 2014

I love Super Mario 64 rather dearly. For once, I agree with the common consensus, and Nintendo did not improve on the three dimensional Mario formula since. There’s a host of reasons why, but I believe we can pinpoint many of those errors on Super Mario Sunshine in particular. Arriving six years after its genre-defining predecessor, Sunshine managed to present a stiffer challenge while changing the physics engine irrevocably with strange, stifling additions and gimmicks.

And you might say “but Super Mario 64 was completely full of platforming gimmicks”, to which I would reply that most of it came strictly from the level design. Your basic move set of jumps, attacks, and abilities remained fixed with small additions like the various hats. They spiced up sequences which the developer set in advance as time trials (since they only lasted a short time, contrary to the permanency of Mario hats in the previous titles). Your main foe wasn’t strange tasks, but an incredibly well-realized physics system that forced cognizance of speed, momentum, and distance. It felt marvelous, and still feels marvelous.

Super Mario Sunshine received a rather tepid reception on its release. At first glance, the Gamecube entry doesn’t really tinker too much with the 3D Mario formula. For all intents and purpose, Sunshine provides the same feel with improved graphics, a tropical theme, and some other miscellaneous additions. It continues the tradition of intuitive design choices that remove tutorials and fluff so that the player can teach themselves how to play. Or so it seems!

The most notable formula shift comes in the jet pack powered by water named F.L.U.D.D. (Hardy har…I do enjoy name puns). Mario needs to “clean” Isle Delfino after being accused of messing up the place. The jet pack lets Mario float temporarily, spray water at foes, becoming a fountain, and use it as a rocket booster. All of these are used fairly well for each of the game’s various Shines (basically, the equivalent of stars for Sunshine). All the various moves you know and love are still here, including the myriad jumping moves, the backflips, and the butt stomp.

However, anyone who played Super Mario 64 enough to do the Bowser stages in their sleep just for fun will notice something’s off. Try running with Mario, then letting go of the control stick. You’ll notice, if you haven’t yet, that Mario magically comes to a complete stop. The jumping physics disappeared, replaced by something with little need for control or nuance. Mario does exactly what you want on the fly, without you need to learn how to control him. While that sounds like an improvement at first glance, looks can deceive.

We might call this the “casualization” of the franchise, beginning here. Every Mario game prior contained within it a pile of sticky frictions and weird interactions. How fast you ran, how long you held the jump button, the directions you held, and a million other ineffable control nuances went into successful jump. You play by feel, get a grip on its strange workings, and then proceeding to navigate through the level accordingly. That’s the whole fun of Mario: getting those physics down to a science, and using that impeccable tool to surpass all obstacles. Good platformers ease the player into a sort of groove where you know the spatial trajectory between you and the obstacles, jumping accordingly.

Sunshine, on the other hand, makes that essential element disappear. You slide when you want to slide; you bowl over cliffs only if you do so intentional. Frankly, it turns the fun process of learning Mario into a set of rout jumping segments and slow movement. Like Mario’s run turning into an immediate stop, Sunshine often does the same. Perhaps F.L.U.D.D. slows the pace down considerably, as its abilities literally create a momentum killer. Good luck running fast, Mario! You need to make this slow jump. Guess they weren’t looking at Tick-Tock Clock when they were crafting these “island themed” levels, eh?

Super Mario 64’s brilliantly wild and abstract levels are replaced by boring real life locations, and it’s all the worse for it. I can’t wait to explore a colorful dock area with oil spills! Yay enviromentalism! Good thing they place arrows to get you back to the location of the Shines, because who would want to explore on their own, right? These systems partly explain why we can’t ever remember the levels themselves anymore: they guided us right through it!

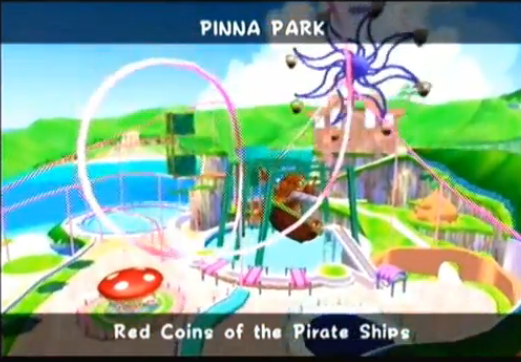

Mario controls fine most of the time, as the Gamecube Controller is perfectly suited to the game. However, even with the addition of the C-Stick, the camera somehow got downgraded in transition. Pinna Park’s awful, awful areas will make that camera jump around for no reason, constantly obscuring your view. I’m not sure who designed those Shines, but I don’t think controlling the camera and Mario at the same time should ever become a prerequisite for solving any puzzles in an action game like this. Many cite Sunshine as a “more difficult” sequel to Super Mario 64, and I tend to agree with them solely based on the camera’s lack of precision! Perhaps the “total” freedom of the camera hampers in this case. Super Mario 64’s fixed, yet somewhat adjustable camera worked much better, somehow; the levels fit the isometric viewpoints, but Sunshine’s fuller locations don’t have any breathing room for the camera.

A great deal of these challenges require obtuse gimmicks, such as (yawn) spraying water on things. In 2002, it felt “innovative”, but time shows the whole concept as a gimmicky little thing. Water turns into the equivalent of Super Mario 64’s punch and kick, except it takes advantage of the Gamecube’s graphical prowess. The squid racing segment in particular annoys the heck out of me, along with all the other strange gimmicks that they jammed into Super Mario Sunshine. The water looks very pretty, but offers little we haven’t seen before as an actual improvement over Super Mario Sunshine’s forefathers.

Actually, the best parts of Sunshine emerge in the occasional secret levels. You suddenly lose your water pack, and must now traverse a set of different sized platforms moving and floating around in space to an end goal. Each of these delectable little segments recreates that wonderful flow you get from Super Mario 64’s tougher challenges, putting pressure on your skills to delivery the victory. Although it does, as aforementioned, lack that wonderful groove, these challenges succeed in showing the longevity of such a simple formula. In fact, they show all the outer trappings of Super Mario Sunshine for what they are: gimmicks.

For all this, though, Sunshine still fundamentally works as a 3D Mario game. As a game with iterative rather than innovative design, it definite tries its hardest to step out of Super Mario 64’s shadow. The game still looks marvelous, and the basic Mario template you expect still works. Hey, you even get to play with Yoshi at points in the game, and that nostalgia highlight still hits the same buttons in my brain.

Yet, all of these exterior elements, appeals to nostalgia, and hand-holding have dictated the path of Mario since, culminating in the incessant tutorials and patronizing messages of Super Mario Galaxy (an incredibly easy game by Mario standards, of all things). I honestly don’t even want to play Galaxy 2, unless someone can convince me that it won’t make everything incredibly obvious and tell me to do what I already know what to do. Galaxy dazzles with graphical effects, wonderful music, and vague sentiments towards Mario games, but it lacks in the heart. In my estimation, they cloud the wonderful elements of Mario, and video games in general, through Nintendo’s straitjacket of casual design.

People did things in the past for a reason. Sometimes, in the constant war drums of progress, we tend to see the past as our enemy, and the future of technological development as king. The past still has lessons to teach us, yet we often ignore them at our peril. Why else do you think we put senior citizens in resting homes, and try to avoid putting old people in much of anything? Because we’ve decided that the past has nothing to teach us. That’s quite a pitfall, and a selective reading of history at best. If we do not know our past, respect our elders, and see the good parts of that world, we will only see previous ages as relics, deservedly forgotten. That train of thought can’t end well. God declares the end and the beginning, so why ignore one in favor of the other?

“Remember the former things long past,

For I am God, and there is no other;

I am God, and there is no one like Me,

Declaring the end from the beginning,

And from ancient times things which have not been done,

Saying, ‘My purpose will be established,

And I will accomplish all My good pleasure’– Isaiah 46:9-10

So it is in video games, so it is in real life.