Last updated on December 3, 2012

TL;DR – Chrono Trigger was, and is, a fantastic and well-crafted Japanese role-playing experience. With the expertise and craft of Hironobu Sakaguchi and Yuji Horii at the helm, two luminaries of Japanese RPG design, each complements the other’s weaknesses, creating something wholly other from their main franchises. The story and battle systems, as a result, reach a level of fine polish that makes each playthrough an enjoyable experience. However, the rest of the game strikes a largely derivative tone – it’s a refinement of a previously established formula, not an innovative creation in and of itself. That doesn’t mean Chrono Trigger isn’t one of the finest role-playing games ever made, but it does mean the structure, mechanics, and narrative elements limit its audience.

Back in 1995, during the days of the dying SNES and the new generation of systems that would change gaming forever, I was a Nintendo fanboy. I may have owned a Genesis, but it was a secondary concern (except for Gunstar Heroes). One day I happend to browse my local Toys R’ Us and came upon one of those demo game kiosk (you know, they used to have a lot of those before we had demos). Guess what game was on it? That day I picked up Chrono Trigger for the price of 69.99 US dollars. Squaresoft’s reputation at the time meant that any game slapped with the logo was a worthy investment of your time. Like most games from that company, Square promised us a world of adventure, excitement, and maybe a little philosophical musing.

There’s no person on earth who would say Chrono Trigger’s a bad game; that much is obvious. However, its glowing reviews as of late have me a bit worried that the hype overtakes the actual product. It’s a fantastic game, granted, but by no means is it revolutionary. Rather, because of the minds behind its creation, it’s no wonder that the game shows us a ultimate a case of iterative design. Polished to a sheen to the point where the sun’s reflection might blind you, it’s incredibly well designed in game mechanics, story, graphics, and atmosphere, it shows us the heights of a particular formula. Yuji Horri and Hironobu Sakaguchi, friendly rivals, collaborated on a game! Dragon Quest combined with Final Fantasy! What could go wrong?

To begin: Chrono Trigger tells an engaging tale. At its most basic, Chrono Trigger provides a contemplative, and well-thought out, version of time travel with the addition of a silent protagonists; echoes of A Link to the Past abound (although that game had dimensions instead of time travel, it’s the same in practice). The events in the beginning take place in a variety of manufactured periods in history, each with a unique flavor and atmosphere. Actions you take in one time period will affect the future – sometimes in negative, and sometimes in positive ways. In fact, it’s remarkable how much thought went into this particular aspect, and it becomes especially clear when the game removes its linear clutches on your party. The sidequests are some of the most brilliant that I’ve yet seen in a JRPG; sure, most of them involve the same “put object/convince person in period X and then visit in future”, but finding out where these people are, how to change them, what to give, etc., really gives you a sense of inquiry and play that most games in the Japanese style do not. They also tend to have entertaining and emotional vignettes that complete several loose ends in the game (except for the one that birthed Chrono Cross).

As for the greater narrative, it’s a story about time travel that’s somehow more logically consistent than just about any other story on time travel ever made (as the aformentioned content makes clear). It’s also a great plot about the concequences of one’s actions, a deep moral tale that never becomes judgmental or too heavy handed for its own good. Yet it also has the time to present a commentary on the powers that be and their constant quest for power – even at the hands of destroying the entire planet. Lavos remains an omnipresent threat to all mankind, and it’s your job to slay him. Yet, unlike in other RPG, Lavos isn’t your main villain – Lavos becomes the tool of a select group of people.

The world of Chrono Trigger has an unbelievable mythology that pans all eras of time; the great part of the game is that all the different time lines don’t feel like they are disconnected when it comes to the story. Little crumbs are left for the player to find, like a grand mystery. Why is 2300 AD so desolate? Where does Lavos come from? Why does Magus want to summon him/it? Why are there constant references to a certain time period that, for whatever reason, remains locked to the player? Everything in the game comes down to 12,000 BC, which isn’t anything like you’d imagine. Islands float in the air, powered by a mysterious force that suddenly dawns on you. Though you discover Lavos pretty early, you don’t discover his real origins until later, where there is a huge conspiracy spanning the history of the world. The corruption of mankind becomes evident, and Lavos becomes the result of that arrogance and avarice. Still, it’s a lighthearted tale with a few moments of existential reflection. Do you doubt for a moment you’ll save the world? No, but you’ll have lots of fun getting there!

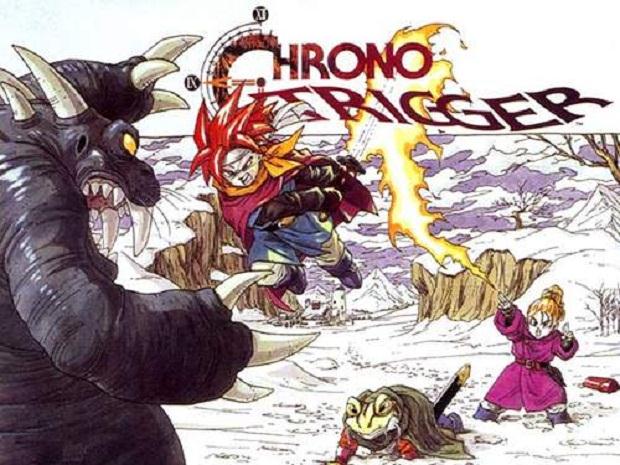

On the actual “game” front, we have the battle system you’d expect. Taking the colorful and personality-filled designs of Akira Toriyama, add the depth and Active Time Battle of Final Fantasy, and you have Chrono Trigger’s battle system in a nut shell. Its single new feature is the Tech system. Depending on which members of the party you have currently, you can use a huge assortment of different attacks that involve 2 or all three members of the party in a dervish of destruction. This could have easily been a phoned-in feature, but it adds some real strategic depth. Learning techs requires each character to learn a specific tech (like most abilities in JRPGs, you learn those by leveling up). Furthermore, bringing those characters into your party forces choice – you can’t have everything you want.

You will receive 6-7 characters (depending on your choices), and each has its own strengths. Marle, for example, has Ice magic and the best healing spells in the game, but suffer in physical attacks and defense. Frog has Water attacks and a strong physical attack and critical strike rating, but suffers from the fact that not many enemies are weak to water. Decisions, decisions! Many of these techs, Double or Triple, also have special attributes that aren’t found normally – they’re worth the high cost (from all party members, no less!) for that alone. Some of the Tech attacks can’t even be learned naturally – some hide deep within the game, requiring special relics to obtain. So yeah, do sidequests!

The bosses, unsurprisingly, are quite inventive. Each really requires strategy, especially the later ones. You know the drill – boss with special ability on cooldown, boss that reacts to special attacks in particular ways, etc. None of them happen to be pushovers, however – it’s nearly impossible to grind, as there aren’t any random battles. All enemies can be seen on the screen. Some you can avoid, but why would you, anyway? Functionally, though, they may as well be random battles – you just happen to know where they are and can plan ahead. Because of this, the game tunes bosses to your current strength, rendering good timing a must, and experimentation is completely welcome (it doesn’t hurt that even party members who aren’t in use stay at the same level as everyone else). What I love about old school RPGs is that sense of dread fighting bosses; it really used to require skill and, in reality, some luck that the computer would do something stupid. Each one is pretty memorable, especially later in the game with multi-tiered boss battles. It’s pretty insane how elaborate some of them become over time; the final showdown especially echoes this sentiment.

One must wonder, then: why not a five star rating? As far as the cinematic feel of the narrative, this also means an incessant linearity creeps into the game. Is it fitting for the game? Absolutely! Stil, the game is fairly linear to a fault; you aren’t going to be doing many side quests (there are all of 12, for goodness sake) and not even until the end of the game. I prefer a little freedom in my JRPG. That’s not a gripe; I can see what they were doing with the game’s structure, with the subtle unfolding of plot details, but it does restrict their ability to expand the world, to make it more expansive, and to encourage more exploration. Furthermore, you will get frustrated and stuck if you don’t prepare. The game rewards the player for paying attention to incidental details (as the story should make clear); if you don’t. prepare for frustrations. The puzzle sections are especially annoying; finding out where to go and when is sometimes a hassle because of this attention to detail.

As well, while the graphics appealed greatly to my child-like disposition back in the day, it has the unfortunate distinction of looking like Akira Toriyama artwork. It’s hard not to think “Dragon Ball Z” whenever you look at the game, and while that isn’t neccessarily a negative, it isn’t a positive for everyone. Some may dismiss it out of hand, and that’s a shame. It isn’t as timeless a look as, say, Yoshitaka Amano’s work on Final Fantasy IV or VI. The much hyped “multiple endings” also add little to the experience. I see no reason to replay the game at all, for that reason at least. Most of them add little to nothing to the story and offer little more than easter eggs to the few willing to beat Lavos in a variety of places in the game.

The one facet of the game’s aesthetics which remain timeless is the music. Yasunori Mitsuda’s first foray into game music may very well be his best. Unlike, say, Chrono Cross or Xenogears, his Celtic influences don’t show; instead, he provides an exemplary, obviously Nobuo Uematsu-inspired score that reflects each time period and each event in the game with great accuracy. It’s hard to forget the strains of 600 AD’s mystical world or 2300 AD’s dark, depressing, and windy landscape with the music attached. The Lavos theme especially brings memories – I’ll admit the whole concept frightened me as a child, and why wouldn’t it? The music became a constant reminder that the end of the world was night unless you chose to save it.

Still, even the music follows the same routine of JRPG music that we’ve heard many times over. The biggest criticism one can level at Chrono Trigger is that it doesn’t deviate far from the same formula which birthed it. We can call it a more focused blend of Final Fantasy V, VI, and Dragon Quest V (maybe even VI; it has a time travel plot, and they were both developed nearly at the same time), but it’s ultimately a sum of its refined part. And this, in some measure, may have something to do with my general apathy towards its critical reception. It does nothing new, yet constantly receives praise that it does something new. It refines and brings depth to things that already exist, rather than making a new experience in itself. That’s what makes it so excellent and so slightly disappointing all at the same time. I’ve had the same reactions and the same joy of play, but I can’t justify giving it a five star given its lack of innovative or unique elements. They’re unique to the genre, yes, but not unique to video games! And that’s the problem with Chrono Trigger: it’s a great game, but not the BEST JRPG EVER!

That’s not a bad thing, though! Every game has its time, as Ecclesiastes 3 would say:

There is an appointed time for everything. And there is a time for every event under heaven—

2 A time to give birth and a time to die;

A time to plant and a time to uproot what is planted.

3 A time to kill and a time to heal;

A time to tear down and a time to build up.

4 A time to weep and a time to laugh;

A time to mourn and a time to dance.

5 A time to throw stones and a time to gather stones;

A time to embrace and a time to shun embracing.

6 A time to search and a time to give up as lost;

A time to keep and a time to throw away.

7 A time to tear apart and a time to sew together;

A time to be silent and a time to speak.

8 A time to love and a time to hate;

A time for war and a time for peace.

And there’s a time for great JRPGs like Chrono Trigger versus the game that came after it (I’m looking at FFVII, of course). I suppose that’s no great criticism, but there it is.