Truth, of course, must of necessity be stranger than fiction, for we have made fiction to suit ourselves.

– G.K. Chesterton, Heretics

One of the primary reason that Christians often don’t like video games, or won’t even entertain buying one, comes down to one simple idea: God designed us to live a real life, not a fake one. An understandable goal, of course; nobody wants to see any Christian sitting in a room all day playing a video game, right? That’s not very Christian in the opinion of many. A relationship with God Himself should take precedence over all else.

I understand this opinion, and confronted it for many years, and in a way I am still haunted by it. No, not THAT question: should I play video games? Rather, this question: are video games just more exciting than real life? Does that mean real life is, gasp, boring? Maybe they just don’t want us to see it when we play video games? Not necessarily! But let’s contrast them both and see what develops.

Categorization and Infinity

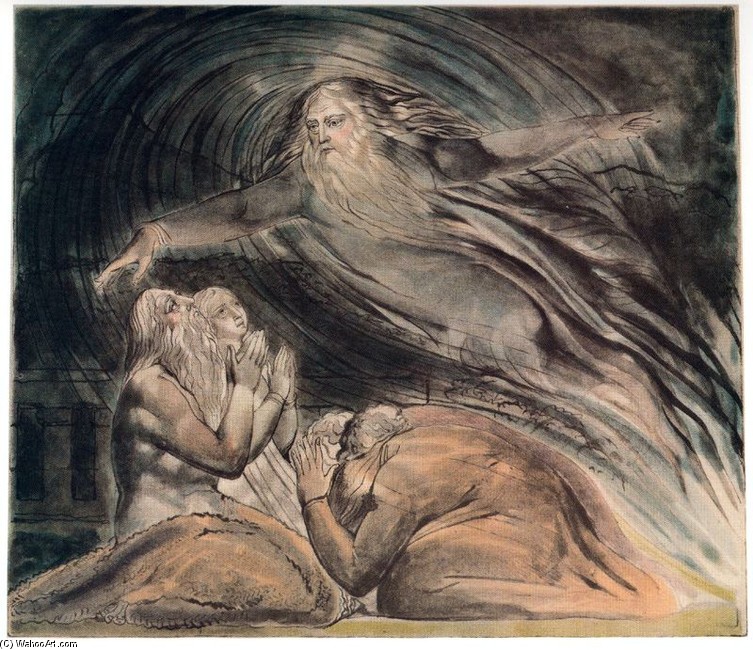

Most events in life don’t fall into a specific category. Life itself may be a system of rules and dynamics, but we are not in charge nor will we ever be in charge of this vast, interconnected system. Christianity teaches us all we need to know – about Christ, about salvation, about metaphysics and many other things. But, in the end, it does not teach us everything, nor does the Bible purport to explain everything. For the modern world, that’s a scary prospect: to not know something. And yet, that’s exactly the answer of Job 38: were you there? Do you know why God does what He does? Probably not:

2 “Who is this that darkens counsel

By words without knowledge?

3 “Now gird up your loins like a man,

And I will ask you, and you instruct Me!

4 “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell Me, if you have understanding,

5 Who set its measurements? Since you know.

Or who stretched the line on it?

6 “On what were its bases sunk?

Or who laid its cornerstone,

7 When the morning stars sang together

And all the sons of God shouted for joy?8 “Or who enclosed the sea with doors

When, bursting forth, it went out from the womb;

9 When I made a cloud its garment

And thick darkness its swaddling band,

10 And I placed boundaries on it

And set a bolt and doors,

11 And I said, ‘Thus far you shall come, but no farther;

And here shall your proud waves stop’?

In a way, we can think of reality as rather open-ended. From our perspective, we cannot weigh all the possibilities. Anything could happen to us, and our actions do not produce an immediate result, whether towards success or failure. That makes life, shall we say, a difficult prospect. Human beings deal in the finite, and we most relate to the finite in our natural state. Beliefs and ideas beyond the effable may be acceptable, but not exactly ideal. We want control over our destinies, even subconsciously, and reality does not work for us. It’s boring, quite, frankly, and without clear goals and rules we can lose interest.

Video Games: An Ideal Reality

Video games, then, emerge out of the way we perceive an ideal reality. If most video games strive for one goal – fun, or the joy of winning while mastering fair game dynamics – then that fun comes from games designed with our human ideals in mind. Thus, a video game focuses on a closed system of rules that engender a player towards certain ends. Whether that’s to achieve an objective, score a goal, or any number of other tasks remains up to the developer. If you feel the fun, then it works. This probably explains the existence of books like Reality is Broken: now we transfer the benefits of a closed system to change reality itself into a closed system.

For millennia, human beings found ways to pass their time. Stories developed out of oral tradition, artwork became a burgeoning source of inspiration (and business), the novel entertained and enlightened, and film brought narrative tropes to a sensory one-two-three combo of dialogue, visuals, and music. We entertain out of a sense of ennui, maybe, but we also use these to point towards greater truths or fulfill a psychological need for closure and catharsis. From a Christian perspective, we wish to point to Christ, who exemplifies all that and more. This is all well and good. But what happens if the fiction becomes more engaging than the reality? Should we impose the fiction that represents our ideal on reality itself?

Video Games in the Christian Space

Hence, the constant talk of video game addiction enters our conversation. Most, if not all Christian writing about video games in English consists of two factors: either the plainly seen moral content of the video games themselves (how much sex, violence, curse words, etc.), or a dire warning against video game addiction. The former isn’t exclusive to video games, although the latter picked up traction as psychologists begin to label many different inclinations under the broad category of “addiction”. Understandably, Christians want to be in the world, but not of the world, and aiding addictive personalities so that they aren’t addictive makes logical sense.

On the other hand, I caution when Christians decide that being “of a different world” also extricates them from the current one. With no knowledge of the world around them, how can you actually teach your kids anything? Restricting access to certain acts proves fatal for most children, who see something like video games as an outlet for rebellion and otherwise. Rules of do and don’t often provide zero context (why should I not do this, parent X?), and that becomes the fatal blow away from a Christian lifestyle.

In that sense, video games feel more interesting by default to the majority of people. We do not grow out of the idea of control and knowledge – we just tend to express it in different ways. Video games represents how human beings want reality to be – exciting, awesome, explainable, and clearly formed to our notions of perception. So how do Christians combat the obvious power of video games?

Is reality really boring?