Last updated on June 24, 2014

So what’s so interesting about detective fiction? There’s a reason why Sherlock Holmes’ popularity endures in popular media, from BBC specials and miniseries like Sherlock to a crazy Robert Downey Jr. flick. Obviously, most of us love a good old fashioned mystery. You’ll also note that, more often than not, the detective stories to which we most relate often take place in contemporary time periods in relatively boring locales. You know the drill: city cops find a mystery, some savant who looks and plays the part of magical mind expert goes to solve a crime.

Sometimes we feel rather angry at their superhuman abilities, but often we just let ourselves into this universe. Things often come together in the most unusual of ways; the ordinary solutions don’t work. Extraordinary happenings emerge out of the humdrum and the usual. You see this in both Persona 3 and 4, with their use of both the suburbs and city life as a space for remarkable events. Detective stories transform the everyday life into the epic of antiquity – with a few edits here and there. Chesterton, one of the most notable writers of the genre with his perenially popular Father Brown tales, knows the score:

There is, however, another good work that is done by detective stories. While it is the constant tendency of the Old Adam to rebel against so universal and automatic a thing as civilization, to preach departure and rebellion, the romance of police activity keeps in some sense before the mind the fact that civilization itself is the most sensational of departures and the most romantic of rebellions. By dealing with the unsleeping sentinels who guard the outposts of society, it tends to remind us that we live in an armed camp, making war with a chaotic world, and that the criminals, the children of chaos, are nothing but the traitors within our gates.

I had always thought Chesterton looked an interesting writer, if not a revelatory one. I began reading the Father Brown mysteries for which he was well known, and reconsidered my opinion considerably for the whole lot! Whereas his “theology” books require several readings to perceive, Chesterton’s a lock at writing short, pitch detective fiction with the most Christian of themes without even directly referencing Christianity in any sense whatever.

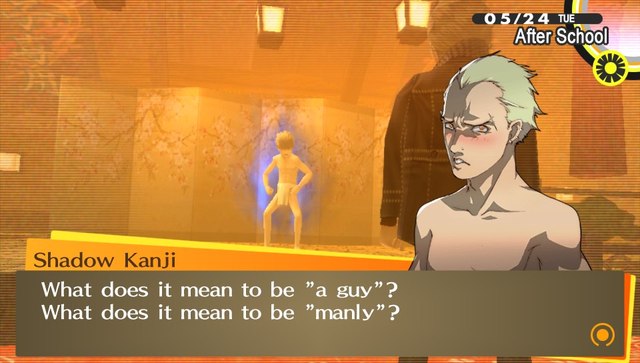

Therein lies the paradox he so amply demonstrates not just in concept, but in technique: Christian values come out of the most un-Christian places if you look hard enough. Law and order, on the other hand, mark a departure from a world of blind chaos. Immorality, by its very existence and recognition, reveals the existence of morality. You see this in Persona 4, considering your uncle works for the police force in Inaba; he doesn’t much suspect that you’re helping him to solve the mystery of the disappearances around town, or the sudden emergence of the Midnight Channel, yet he does have a sneaking suspicion that you’re helping. The forces of good, both physical and spiritual, have their own roles to play against evil, and surprisingly Persona 4 holds a sense of inner justice that you wouldn’t expect. The detectives who stand alone with the ability to solve the mystery hold a far greater significance then we suspect:

When the detective in a police romance stands alone, and somewhat fatuously fearless amid the knives and fists of a thieves’ kitchen, it does certainly serve to make us remember that it is the agent of social justice who is the original and poetic figure; while the burglars and footpads are merely placid old cosmic conservatives, happy in the immemorial respectability of apes and wolves. The romance of the police force is thus the whole romance of man. It is based on the fact that morality is the most dark and daring of conspiracies. It reminds us that the whole noiseless and unnoticeable police management by which we are ruled and protected is only a successful knight-errantry.

For once, the detective stories highlight the good guys – or, at least, in their most exemplary form they do. Such tales admire the police officer, the detective, and the person solving crime. It does not admire the criminal, but tries to find him or her in the act, to discover the trail of the chaotic and bring it back into order. In other words, they become our modern day knights, the keepers of the peace. The real role of the police and authority, although mostly forgotten now in cynicism from popular media and fear, is to keep the peace. They arbitrate conflict and bring people to justice, according to the ideal of society.

I think we could make a fair case that Christianity established Western civilization as we know it, so that isn’t so far beyond the pale as you would imagine. Christian morality inevitability makes its way into detective stories because a clear right and wrong often emerge. The facts bring evil into light; reason and logic pull darkness into the sun’s warm embrace.

Detective stories represent that Christian ideal by turning them into upstanding citizens who, even through their personal problems and human flaws, help civilization regain its footing with a moral character. They’re not terrified of the common man, but want to help them. It’s a totally different outlook, yet it derives from the many classics of literature and human achievement. That’s difficult to see in our age, but essential nonetheless!