Last updated on April 22, 2013

McDroid was one of those weird surprises at PAX. I did not hear anything about this game from any websites, nor did I know such a thing existed. Thank goodness I lost Mr. Cauller when he went to the bathroom, or I probably would have missed it entirely! Games coverage takes precedence over friends, don’t you know?! Also, Mr. Cauller immediately disappeared after that and I didn’t see him for a couple hours after that. The bathroom lines were long, but not THAT long. Who knows; weird stuff happens when you wake up at 2:00 AM, drive many hours and then run a booth all day on little-to-no-food.

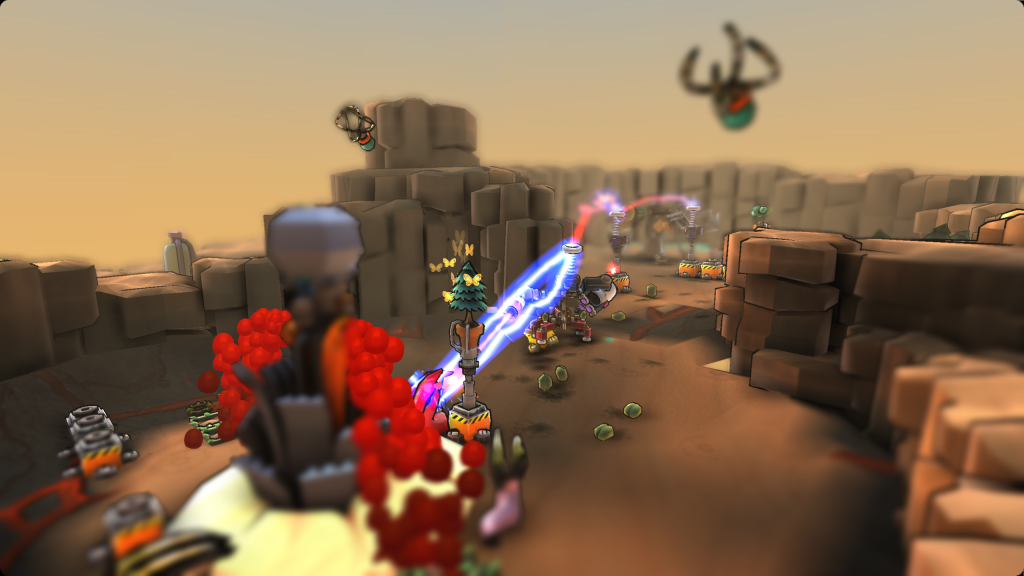

Anyway, stuff about McDroid now! I see a little Dungeon Defenders in the game, at least from the visual style and the format, yet I am sure that isn’t intentional. Elefantopia, the developer of said game, describes it as a fusion of action and real-time strategy, the lovechild of R-Type and Dune 2. That might not mean a lot to you all, but let’s break that down. Dune II wasn’t the first RTS, but it certainly laid the blueprint for all the ones that came in the future, including everyone’s darling StarCraft (I guess WarCraft also, but everyone associates the brand with MMOs now, so it’s not that applicable anymore), Command & Conquer, and Age of Empires. It established the idea of resource management and economic development in the genre – for the Dune universe, one uses spice to build stuff and uses spice gatherers to get said resources. Then, you use those resources to build military equipment in order to destroy your enemy. Resources allow one to build other buildings, and these became part of a technology tree requiring certain buildings before others could be placed. Some buildings could move around as mobile units in their own right. In addition, the game provided three different factions to play, each with their own unique units and super weapons. Describing it this way makes it sound like I’m being condescending to the reader, but in 1992 all of this stuff was new – nobody had quite done it quite like this.

The real time strategy games before this did not give such a heavy focus to resource gathering; Herzog Zwei, another excellent real-time strategy game in its own right (and probably the first real RTS game) let you build eight different units that could be outfitted with several different programs that determined their AI paths. Even though you needed to capture bases to get money for the purpose of war, it adopted a more aggressive style. Dune II, however, somehow became the standard (more than likely because Herzog Zwei was, and is, obscure and came out in the early days of the Genesis when it sold terribly, but that’s a different story). However – and this is the fascinating part – Herzog Zwei controlled like a top-down shooter. You are the spaceship, yet you can’t attack – you need your units to help you in that endeavor.

McDroid emphasizes this sort of management in a tower-defense style format. You have a central base, a map, and you have options to place towers of many different types around the area. Some look like the common turrets, while others grow plants…which is to say, this game doesn’t take itself too seriously, but also that the main resource of the game is strawberries. Yes, strawberries, and you need plant-growing turrets to grow them. At the same time, you’ll also deal with wave after wave of enemies that want to kill you and all your stuff (again, not very descriptive). Of course, there’s only one resource – it’s there mostly to keep you busy when nothing’s happening, or constraining you to finding resources when on the brink of defeat (or find yourself needing an essential upgrade). It’s an elegant way to make sure the player always remains on their toes and becomes prepared for the next encounter. Plus, the location of the strawberries, and where you need to make them grow, lets the developer focus the places of conflict.

Like Herzog Zwei, you’re not that powerful in and of yourself, but you need to gather resources like in Dune II. However, the R-Type influence changes the game quite a bit from its roots. R-Type remains one of the premier shooters of that genre’s early renaissance in the late 1980s. A side-scrolling shooter always had a unique mechanic to hook the player into the simple experience of shooting, and R-Type distinguished itself with the floating Force pod. Think of it as a floating, yet invincible, part of your ship, that fires when you fire. Not only could you attach this to the front for increased firepower, but also on the back when you needed to cover both directions in harrowing situations. As well, you could let it simply float about and gain the ability to fire at multiple places at once. Given that it is also immune to bullets, the Force pod’s use as a shield allowed the designers to create incredibly difficult level designs requiring good use of the provided tools. In fact, it’s almost like an action puzzle game where you memorize the right sequence while also developing the reflexes necessary to avoid damage (one hit kills, unsurprisingly). R-Type, like its contemporary Gradius, remains legendary for its uncompromising (just for you, Josh) difficulty and innovative mechanics.

McDroid, though, looks to ease the learning curve on the whole Force pod thing. You get to choose it this time (well, excepting later R-Type games)! Your little spider-craft thingie (sorry, not very descriptive) can carry turrets around and plop them in specific spots, so you can carry the growing turret to the strawberries and gather them up. You carry weapons on your back, more or less – but you, as the player, need to gather the resources by hand instead of leaving it to your worker drones. While you’re not the strongest thing on earth (after all, you can only carry one turret), your special ability lies in quickly setting up turrets, gathering resources, and knowing when to run away. Not dying seems like an essential portion of the game, as that halts all your multitasking and probably leads to defeat. The spider’s still fragile – hence, his fast speed – and you’ll need quick movement and good forethought to succeed. If that doesn’t show us R-Type in a nutshell, I don’t know what does – that you can memorize the waves probably adds to this same feeling.

Add to this a much-lauded “Nightmare Mode” – which makes some of the stage impossible to complete so far, and no one at PAX East could finish it – and you’ve got yourself quite a challenge. A complicated game doesn’t need complicated sets of moves, but it can easily present you with a few options performed at the right time in the right way. The skills McDroid tests follow that ever-present adage of “easy to play, difficult to master” that many developers so frequently try to achieve and fail. In the time I played, I got a basic idea of the design and the feel, and most of the above seems pretty representative of the game as a whole. Add four player co-op (again, Dungeon Defenders) and you’ve got the basic idea for an excellent game, at least when it’s finished.

Honestly, it’s a wonder that innovative, yet still traditional, games like this don’t get more press. I would not even know it existed (nor would you, dear reader) without me talking about it. These kind of games seem like the future of our hobby – as AAA games continue to rise in costs and the risk gets so high that the experience becomes completely homogenized, independent games revive long-lost genres, games, and types of play into new and increasingly excellent forms. McDroid captures the soul of its creators, and even the games that inspired those who created in the first place. Mechanics get passed down even in a short span of time, and this surprises me whenever I take time to research older games – it’s simply amazing how many times you see old tropes given a dash of paint, a little mechanical overhaul, and suddenly we’re in a different genre.

But, proven things work, and one of those proven things comes down to satisfaction with the core game’s elements. Some designs prevail, and others do not, and McDroid’s based on games that, while barely known to all but the hardest of hardcore, carries their spirit with it. You see this in nearly every endeavor of human culture: some things persevere, and others go away. Some disappear for a time, yet return all the more – history is cyclical, ever-repeating the same old tropes because, well, that’s what we do. Our problems and our joys and our desires haven’t changed much since the beginning of time, nor do I expect them to change (maybe in the next world). It’s the same way that William Barclay points out:

There is one eternal principle which will be valid as long as the world lasts. The principle is—Forgiveness is a costly thing. Human forgiveness is costly. A son or a daughter may go wrong; a father or a mother may forgive; but that forgiveness has brought tears … There was a price of a broken heart to pay. Divine forgiveness is costly. God is love, but God is holiness. God, least of all, can break the great moral laws on which the universe is built. Sin must have its punishment or the very structure of life disintegrates. And God alone can pay the terrible price that is necessary before men can be forgiven. Forgiveness is never a case of saying: “It’s all right; it doesn’t matter.” Forgiveness is the most costly thing in the world.

Yet it is that one principle that remains the key to the whole Christian message: forgiveness. Forgiveness has done mighty things in the course of human history, and even if it remains one of the hardest things for us to do, it is essential. Or, as Colossians 3:11-12 puts it:

12 So, as those who have been chosen of God, holy and beloved, put on a heart of compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience; 13 bearing with one another, and forgiving each other, whoever has a complaint against anyone; just as the Lord forgave you, so also should you.

Although, perhaps, the ability to destroy evil creatures and prevent them from destroying your rocket shuttle isn’t quite the same, the underlying mechanics show, in a microcosm, that some principles just seem to work – however much people may call for something “new” all the time. Consider this a recommendation: go buy it when it comes out, and vote for it on Steam Greenlight.