Last updated on May 31, 2014

Submitting

In this particular chapter, Peter tells his readers that political institutions and earthly authorities exist because of God:

13 Submit yourselves for the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether to a king as the one in authority, 14 or to governors as sent by him for the punishment of evildoers and the praise of those who do right. 15 For such is the will of God that by doing right you may silence the ignorance of foolish men. 16 Act as free men, and do not use your freedom as a covering for evil, but use it as bondslaves of God. 17 Honor all people, love the brotherhood, fear God,honor the king.

That’s not exactly a call for “freedom”, now, is it? We could view it as a result of historical context – the Roman Empire existed as quite a different state entity from modern governments, surely. The Emperor, at least at the time in which most of the Epistles were written, acted upon his authority as no less than a god. However, 2 Peter affirms that God rules over that God, and that the little one follows the Big One, if you know what I mean. Do right and fear no man.

In none of this, however, do we see our writer complain about how unfair their particular situation makes life. He does not recommend a bitter, muttering-under-one’s-breath attitude, nor a simple wave of the hand. Rather, he says “submit to authorities, because God’s in control”. That same control does not imply fairness. If you read Psalms, there’s a continual focus in many of David’s words on the righteousness, promises, longsuffering, and lovingkindess of God. On the other hand, David laments at how life, for lack of a sentence with more impact, sucks when evil people get away with murder (literally or figuratively).

I find this so strange, and perhaps that’s why I always find myself at odds with “rights” language, but this is an aside for another day!

You could, in fact, think of God as an alternately positive and negative presence, both of which shape human character. God does not promise fairness, but promises through faith. 2 Peter continues to give us that similar sentiment: good and bad rulers alike exist as an opportunity for the Gospel’s main credo to flourish:

18 Servants, be submissive to your masters with all respect, not only to those who are good and gentle, but also to those who are unreasonable. 19 For this finds favor, if for the sake of conscience toward God a person bears up under sorrows when suffering unjustly. 20 For what credit is there if, when you sin and are harshly treated, you endure it with patience? But if when you do what is right and suffer for it you patiently endure it, this finds favor with God.

And you’re just supposed to take it! I know that I, myself, tend to rail against the establishment and the thought that arises out of the establishment. The key for me comes from balancing that desire to help people understand my perspective with a respect for their opinions. Trust me, that isn’t an easy task (and no pity parties here, just saying), but obviously the Bible tells me I need to follow this dictate in some way.

Comparisons

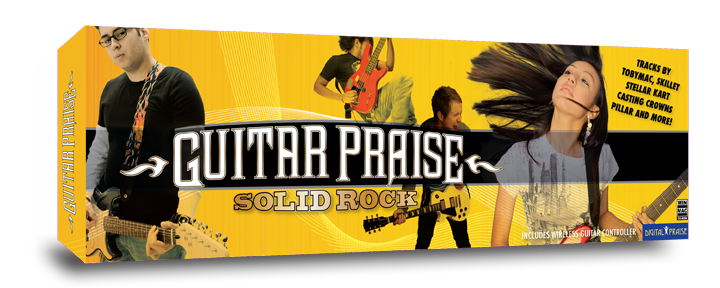

Contrast video games with Christianity, and you’ll see that what works in one realm actually doesn’t work well at all in the other. Games and fun (the challenge of mastering fair game dynamics) require that innate sense of fairness that renders possible, if highly varied, optimal strategies. Christianity, on the other hand, requires no such thing from human existence – times will be tough, and things will get bad, and only God will get you through that. A lifeline does not equal a balanced scales for every human being in existence. Outrage against injustice is warranted, but it is also an inevitability. Of course, we’ve already discussed that perhaps that might just emerge as an endemic result of our collective upbringings with the promise of “equality” and whatnot.

Demands for one strike me as completely different from the other, at least viewing the issue from this angle. So do we try to fix this, or do we let them live at opposite sides of the street? Do we criticize one to fit the other, or will they remain eternally at odds? One could make the case that indie developers made strides towards that end, but they consists of a relatively small portion of the market as a whole; for the most part, video games are as games in general have been forever. At such a juncture, I imagine you expect a proper response from me, with all the in-depth explanation and structure you’d expect. Unfortunately, my answer really consists of “I don’t know”. Because, seriously, I don’t know.

I know what makes video games as they are work, that much is for certain. A good action/puzzle game needs satisfying mechanical interplay, a holistic design to make it matter, and an ever-escalating series of challenge. A strategy game needs many options useful in multiple contexts and usable in myriad ways to achieve the main objectives. A good RPG often tells a compelling story whilst pairing that narrative with a meaty battle system or statistics distribution for maniacal completionists (wait, scratch that one). A game that wants to bend the genres together needs to take advantage of their unique qualities while sacrificing none of their immensely good qualities. Much of these games I discuss in detail on The List, and that’s all well and good.

However, I often find myself with the strange compulsion that I definitely player Title X before, no matter how many weird quirks it contains. There’s only so many things a medium (if you want me to use pretentious, artsy terms for video games) allows before it starts to crack and strain. No matter how good the story, graphics, aesthetics, mechanics, or whatever else, we’ve seen much of this content before. At the very least, the video game market seeks to refine its ideas to a fine, almost impossibly shiny, sheen. Such reductionism, isn’t it?

Making a game “unfair” and “real” just tends to bring us “less interesting” as a result. If I wanted that, I’d rather get it in real life than engage in some vicarious, and sorta creepy, virtual foreplay with the Real. The benefits of video games often come from beneficial recreation or escapism, the whole reason why God rests on the seventh day and why the Sabbath must be kept holy. Perhaps we should just keep them separate and on their own trajectories. Perhaps they merely fit in different categories of “Christian” thought than we often force “artistic mediums” to provide (i.e., if it worked for plastics and motion pictures, it’ll certainly work for vidya games!).

Christianity just doesn’t neatly fit as a concept into video games – but that depends on what you mean. That, at least, is my primary conclusion at the moment. As a person who does not often attempt to predict the future, I cannot really say. Have you seen any true change in the formation of games? They tend towards the same ideas with infinite variations, all well and good, but they certainly don’t go for “unfairness” very often.