Monday Update and me playing video games. That is good!

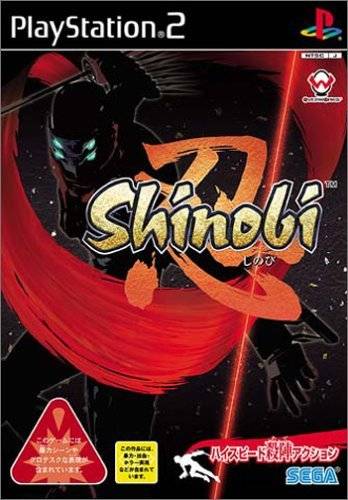

Shinobi (PS2) – I’m trying to figure out why the American box art for this game looks so horrible; why is there a prerendered version of a character just BEGGING for some kind of anime art?

Oh, ok. See, that’s better. Go go long red scarfs!

I’ll be honest: I never played any of the Shinobi games prior to this one for a considerable length of time. If my memory serves me right, we had a Sega Master System in our house and a copy of Shinobi, but I could never get past the first level. So, as far as the series goes, this remains my first foray.

And what a foray it is! Let’s say my personal preference never slid towards Shinobi versus the Ninja Gaiden remake. I always believed (and my List entry confirms this) that Shinobi seemed a horrible ripoff. Yet, Ninja Gaiden contains hosts of feature unneccessary for completion or mastery. For example, the game contains myriad combos but only a few ever strike the player as necessary; the rest exist out of some perfunctory desire to make it more complex and like a fighting game (not that AI foes could be caught off guard by attack variety). Nor is there a “style” system reflecting the use of varied attacks. The adventure elements, while good for pacing, do cause moments of lull in-between larger sequences. That doesn’t mean it’s an exemplary game, but a few elements shift the newer NG games into territory which they don’t have to traverse at all for success; it is just bloat.

Shinobi’s laser sharp focus on a single set of mechanics (even at the expense of art design and other “features” that modern developers shove into their games) comes into its own if you force yourself to learn them well. Your main character, Hotsuma, has all of one attack button, a light speed dash for quick movement, and a double jump. At times, he needs to wall run, but that’s about the gist of the whole game (some other hidden moves come into play, but that’s for you to discover).

See, Shinobi requires the player to navigate levels as fast as possible. Your sword, Akujiki, continually drains life from the player over time -your Yang meter drains over time until it starts taking Yin, or life, from Hotsuma. Satiate its blood lust with the death of your enemies; the more enemies you kill in a row, the more damage your blade deals. Kill four or more enemies within a certain time frame (usually quite short!) and you’ll perform a TATE attack, damaging all enemies on screen for massive damage and instantly killing everything else. These usually provide you with lots of Yin (or health).

Thus, every part of the stage becomes a race to completion. Every time you need to solve a puzzle or find objects in the environment becomes another moment wasted as Akujiki starts to drain your life. It’s a harrowing, yet unbelievably satisfying experience – the forward driving impetus remains ever-present even during boss fights, meaning every encounter becomes a tense game of efficient destruction and survival. Enemies will continually try to thwart you, and you’ll need to use every option at your disposal to defeat them. You can even kill most bosses (one at the end of all sixteen levels) in one hit with the TATE, but you need to be very efficient and learn every boss pattern to succeed at this objective.

It is, at heart, an old-school game unwilling to forgive the player for mistakes. Although you can restart at a boss encounter if you die, levels don’t have any checkpoints. Considering these ten minute long levels throw a lot of bottomless pits, platforming, and enemy killing at the player, the game asks a lot of your reflexes, skills, and strategy to conquer. At least the levels go for a bout of excessive linearity; it’s rare that the player loses their way in these hallway-like stage designs. Even aesthetics bow to the perfection of the game’s mechanics! Don’t expect to waltz into the game and merely complete it – you must master the mechanics, or Akujiki will suck the life out of you without remorse and without mercy. Of course, with all this difficulty and frustration comes the promise of satisfaction and a sense of completion.

And, furthermore, I compliment the design for making me feel like a ninja rather than a glorified Dante clone. The urgency of all its elements forces the player to think quick, act quick, and move quick. You cannot slow down for a single second. You need to adapt to whatever situation appears – thus, the common stereotype of the ninja totally immerses you in the experience. You can’t even think of anything else beyond the game; you must play this role, or you will succumb to the sword or your enemies. Shinobi so brilliantly succeeds at a holistic mechanical construction for a video game that the immersion comes as a secondary component.

If there’s anything weird about the game, it lies in the insistence to include cutscenes and a very self-serious story. Seriously, when you’re attacked by magical ninja dogs with knives in their mouths, it’s hard for me to take any of this ninja revenge bluster seriously. Not that I much care; skipping everything won’t hamper your experience in the least. Like other Shinobi games, the video game part remains supreme rather than the story; the rest just gives context to your actions.

I’ve bought the game twice now (both times for under ten dollars; once at a Blockbuster Video, and the other off eBay when I needed a fix), and neither time did I regret it at all. The new PSN price tag of 9.99 USD should convince anyone else to go try it if you’re looking for a big, satisfying, and fair challenge. I’ve still got half a game left to go, though, so we’ll see whether the core mechanics hold up to closer scrutiny.

I hear the sequel (Nightshade) isn’t half as good, so there’s that! And Ninja Gaiden II and III certainly don’t come close to this masterpiece.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

As said before, much gushing ensues. So there you go. Look forward to a review this week (it’s been a while!).