Bodyguards and Assassins – This film takes place in 1906 at a pivotal moment in China’s history. Around this time, Sun Wen (better known as Sun-Yat Sen) desired to see a free China. The corrupt Qing dynasty oppressed the people according to the film, and Sun Wen’s supporters sought to establish a people’s republic wherein all men are equal, rather than divided by class or creed (sound familiar?). To do this, Sun Wen needed to return from his exile in Japan to meet with revolutionary leaders in Hong Kong; of course, the Qing dynasty plots to kill him if he so much as steps foot in the city. So do our protagonists come together, for reasons political and personal, to defend Sun Wen from evil forces. There’s much more to the film than that, of course, but to say anything else would spoil the film.

Bodyguards and Assassins – This film takes place in 1906 at a pivotal moment in China’s history. Around this time, Sun Wen (better known as Sun-Yat Sen) desired to see a free China. The corrupt Qing dynasty oppressed the people according to the film, and Sun Wen’s supporters sought to establish a people’s republic wherein all men are equal, rather than divided by class or creed (sound familiar?). To do this, Sun Wen needed to return from his exile in Japan to meet with revolutionary leaders in Hong Kong; of course, the Qing dynasty plots to kill him if he so much as steps foot in the city. So do our protagonists come together, for reasons political and personal, to defend Sun Wen from evil forces. There’s much more to the film than that, of course, but to say anything else would spoil the film.

And hey, I felt like watching some Asian cinema on Netflix, and this looked to fit the bill for that particular period. The premise certainly interested me, and considering this led to the establishment of the Republic of China (pre-Communist), an expose of a particularly unknown (to the West) and tumultuous period in China hit me right in the “gathering somewhat useless information” nerve.

Boy, did my instincts prove wrong!

We could lump the film into the category “historical fiction”, and in that sense it works as both a piece of exciting kung-fu political drama and propaganda for both sides of the Taiwan Strait (apparently, Sun Yat-Sen is rather popular on both side of the “true China” fence). Unfortunately, in the same vein as The Patriot, another well-know film that could fit easily in the same genre, nearly every single thing that happens was completely manufactured out of the blue. In fact, though some actual people populate the cast, almost every person with any character development exists purely in the minds of the writers rather than any true history. The kung-fu exists for spectacle and entertainment rather than information; the various dramatic conflicts seek to touch your emotional nerve, and it does work wonders in this regard, but the realization that a falsehood inhabits your inquisitive mind isn’t exactly delightful.

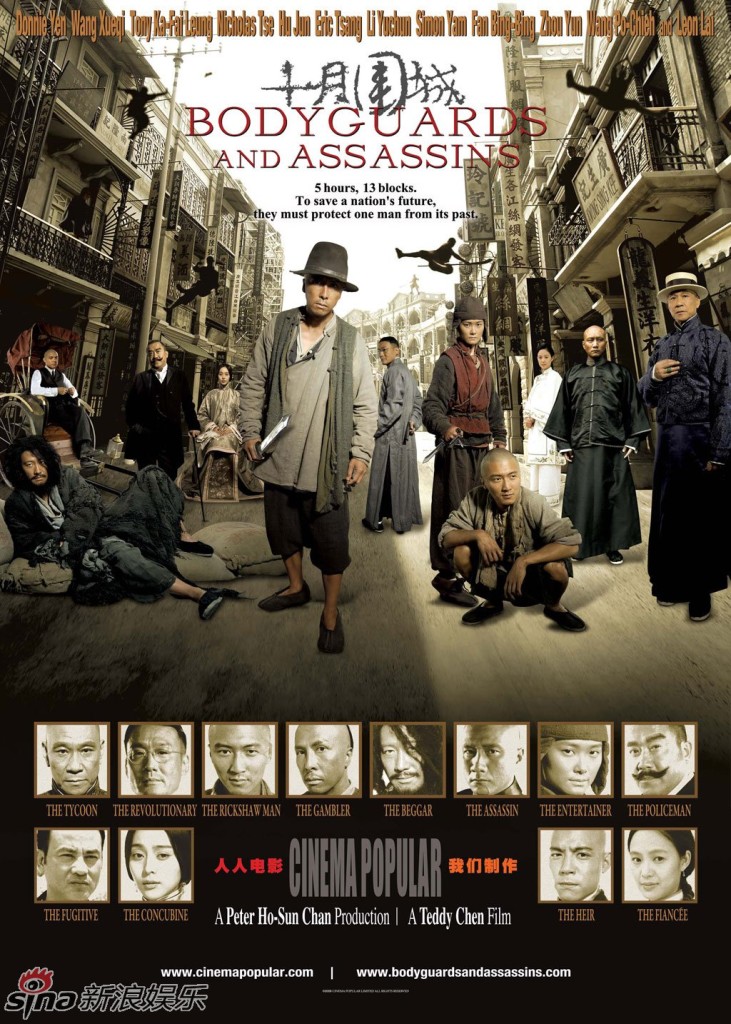

I realize that film-makers MUST attempt to appeal to their audience, and that fudging the facts certainly leads to a more entertaining story. However, even the plot fails to make sense at some points. A Westerner trying to keep track of these characters, their motivations, and the ideals of an entirely different culture (I would call this Communist propaganda, at some level) turn this into a relatively confusing film. Should I know who these characters are? Would the original audience know? You wonder why Qing forces couldn’t tell where Sun Wen actually met; you also wonder why there’s some people sound like conduits for a political party rather than actual people ( “The Heir”, as he’s called in the poster above, demonstrates this especially well). And would Sun Wen even say things that sounded like revolutionary fervor, that sacrifices must be made and blood must be shed? Thematically, yes, this works within the film. But does it in real life?

Part of the problem is that Sun Yat-Sen’s primary motivation came from his conversion to Christianity. This conversion changed him, and furthermore affected his entire political destiny. As you might expect, they gloss over Sun Wen completely in the film as anything other than a mouthpiece for vague notions of revolution, and not so much in the Western cultural sense that he continued to espouse for most of his life. Sun Wen helmed many, many failed revolutionary attempts, not successful ones, and he almost predominantly desired non-violent negotiation and protest over violent conflict. In this film, he sounds like a hungry warmonger who must sacrifice the few for the many, and the historical Sun Wen would balk at such statements. Harold Schiffrin, who wrote the definitive Sun Yat-Sen and the Origins of the Chinese Revolution, says:

While dedicated to the aims of revolution, Sun preferred the least forceful measures for achieving them….For all his audacity, Sun lacked the ruthlessness that marks the true revolutionary. Put simply, he preferred negotiating to killing, and compromise to prolonged struggle. These were qualities that made him seem quixotic and strangely unrevolutionary, but more genuinely human

Either I interpret this as a facet of Chinese education lining up with the film’s version of events, or I merely accept the ideology of the writers at face value. In all honesty, I can’t imagine many people can separate the politics that shape the history here from the story itself. I apologize for inundating the reader with all of this information, but the actual tale spun here will not work to everyone’s taste. Fair warming, then, for anyone who stumbles upon this pseudo-review.

Given all that, the film’s well-designed and will keep your interest throughout. Not knowing any of the facts listed above prior to enjoying the film itself, I feel that it deserves at least one viewing. The choreography’s quite exciting, it’s absolutely amazing that they physically built an entire recreated Hong Kong circa 1906 without CGI, and there’s a host of great acting performances by an absolutely gigantic ensemble cast. At least Teddy Chan, the director, takes his time setting the stakes rather than throwing two and half hours of action at us. If anything, I don’t understand how the Qing dynasty or Manchu forces or whatever were oppressing anyone, so I am missing that particular portion of the puzzle.

There’s a few less-than-believable scenes (like, seriously, how could a guy get stabbed so many times), but imagine this as glorified history and it will work fine. I am absolutely fine with an exaggerated history, as I’m sure long-time readers of the blog will know. I was just hoping to learn new things, and the film ignores history to a degree I feel goes way too far. If you delve into this world, you must simply be cautious for the kind of belief system you’re observing.