Note: spoilers of all kinds ahead, but considering the game is about 4 years old at this point, I think the statute of limitations on such things expired.

What is Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain? In some ways, we might call it a fundamentally unfinished game. Kojima divided the game into two chapters: the first called Vengeance, the second called Race. The first segment is a perfectly paced, unbelievably well-designed open world game with a clear plot arc. The game tells its fascinating tale through small cutscenes (contrast to Kojima’s usual overlong style), episodic Missions (with opening and ending credits like a television show) and audio tapes which detail plot that couldn’t otherwise fit. Kojima Productions uses every tool at its disposal to sell its story, rich with thematic details and interesting tidbits. It doesn’t clear up every piece of Metal Gear lore; that would be impossible, given the series’ penchant for endless retroactive continuity, but it comes pretty close.

The second chapter, on the other hand, sets up many plot threads and doesn’t resolve them. Most of the Missions consist of repeat Missions with new constraints, like Subsistence (no equipment at the start), Extreme (it’s harder, I guess?) and Total Stealth (self-explanatory). The title card for this Chapter seems surprisingly absent, as the subject of Race almost never appears at all. Rather, a few extra, finished missions end up overwhelmed by over 12 repeat tasks which you already did. Then, one more Mission opens up, you repeat yet another Mission from the beginning of the game, and suddenly the game’s over.

Huh? Miller gives a weird speech after Chapter 1, and it felt like the story was complete. But then it wasn’t?

We hold our rifles in missing hands. We stand tall on missing legs. We stride forward on the bones of our fallen. Then, and only then, are we alive. This “Pain” is ours and no one else’s. A secret weapon we wield, out of sight. We will be stronger than ever. For our peace … Still, It doesn’t feel like this is over.

– Kazuhira Miller

CHAPTER 1

REVENGE

Trust me, I was just as confused as you when I finished it. The climax appears with no warning, no grand climactic act; Metal Gear, as a series, simply ends with a very minor series of revelations which, while satisfying in their own way, will fail to satisfy the majority of Metal Gear fans who want the answers. In that sense, The Phantom Pain belies expectations on a number of levels. But, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s talk about the amazing mechanics first.

Kojima finally held at his command the resources to create what I’d call an “open world” stealth game. While previous games in the series railroaded the player down a predetermined, plot-driven path, The Phantom Pain provides a similar degree of freedom as in Peace Walker. Like its immediate Metal Gear (Solid) predecessor, the game tasks you (for very different reasons, of course) to play the role of Big Boss in his quest to obtain revenge against Skull Face for the events of Ground Zeroes, and also rebuild Militaires Sans Frontières, the organization that was destroyed and disbanded over Big Boss’ nine year coma. In 1984 (not coincidentally the year of George Orwell’s novel), Big Boss along with his cohorts Kazuhira Miller and Revolver Ocelot create Diamond Dogs, yet another private military organization, this time dedicated to the task of doing anything and everything to find out who wronged them to put them to a particularly PMC brand of “justice”.

As such, the player takes on a variety of missions for a variety of causes all around Afghanistan and the Angola-Zaire border, both warzones at this particular moment in history. Venom Snake, as he is known throughout the game (since Big Boss always seems to obtain Snake-related names), choppers into the location while receiving briefings from Miller, and sets off to stealthily (or not) infiltrate enemy compounds. The game, at this point, presents you with the freedom to go about an open world setting, analyzing your enemies from afar while devising an effective plan of attack or avoidance before making a commitment. You choose the time of day or night, as each presents its own unique challenges, but the game sets the pace. At this point, Metal Gear Solid V gives you the impression that Kojima loved Peace Walker enough to re-use its structure, especially choosing missions from a menu.

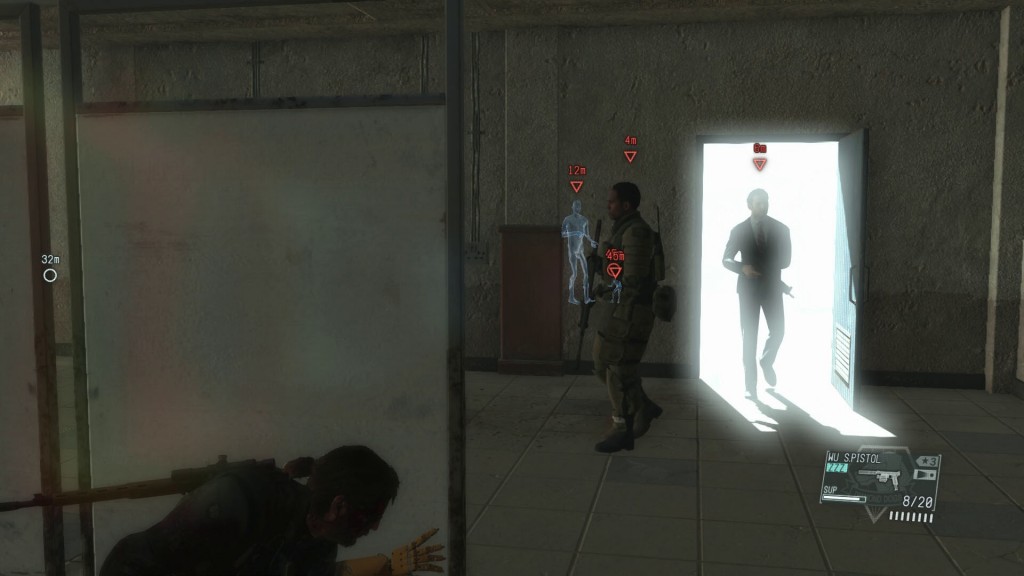

Even so, unlike its immediate predecessor, Metal Gear Solid V eliminates the Soliton Radar (making it much more like Snake Eater) of earlier entries in favor of the Marking system. For those of you who played Ground Zeroes, this will seem like old hat, but it’s worth discussing nonetheless. Literally, you use a pair of binoculars to scope the dangerous areas in advance, which allows you to tag and observe solider positions from any distance afterward. However, this also means that you only know the position of soldiers you can see; as such, no stealthy infiltration starts with perfect information, as in real life, and the game constantly keeps you on your toes in this very regard. While soldiers guard the compound, each has its own set of observable AI patterns that can vary on circumstance. Transport trucks and jeeps might pass the area just as you decide to take action, or additional troops might suddenly arrive with little warning. Listening to soldier conversations (another useful function of the binoculars) can also provide you with essential details and future events. Literally every Mission, even Side Ops, require significant reconnaissance, which gives quiet time for the player to get the gears turning in their heads. That you don’t lose markers after failure or death is a nice touch, since it would be rather tedious to re-mark all the enemy soldiers in this manner once you’ve done the work.

No matter whether you decide, a silent or loud entrance is in order! The game then tasks you with the real work of fulfilling the Mission requirements. For an open world game, each and every enemy outpost and fortress seems filled with excessive ways to crawl and stealth around. I can’t imagine the number of possibilities on order here; each player will try some fundamentally different approach to myself. As for me, I tried as often as possible to take a completely silent, non-lethal approach. Unlike previous games in the series, they balance out tranquilizer darts by requiring headshots for immediate effect, and giving suppressors limited use so that you can’t simply snipe around willy-nilly. You can use trucks to move around, crawl out of sight of guards during the day, and slowly tiptoe your way to additional information via knocking guards out with chokeholds. The level design somehow encompasses the best of both world by allowing for myriad different methods of attack, while also giving a solidly, carefully crafted level at the same exact time. The close-quarters Missions with ex-filtration usually do this best, as they require you to go in blind once you get into the building; getting out is part of the fun! I like to think of this level design as “confidently inefficient“, in that they sometimes feel designed just for players to invent new methods and tricks to complete their objectives.

The soldier AI contributes a great deal to this. Unlike in previous Metal Gear games, they can actually see you at a far distance, at least far enough to force a cautious approach towards any enemies in sight. Guards who don’t see you won’t raise much of a stir, but that doesn’t mean you can easily predict their path of movement. Sometimes, they’ll go to a new place just for a quick cigarette, or have an extended conversation with a fellow comrade. In any event, you can never be too sure of their fundamental path; you need a good sense of the layout, and the good sense to stay out of the other guard’s site, to take them down up close. Enemies react not only to sight, but also to sounds; little objects on the ground can, if you walk too fast, alert enemies to your presence, and that even follows for your basic movements! If you interrogate soldiers, his comrades can hear it, and thus you need to be extra cautious around them.

As well, if guards do see or hear you without knowing what it was, their reactions to that suspicion vary from guard to guard. Some guards go into the thick of it to investigate; others call in their superiors, or other guards, to aid in the search. If that man fails to report in, what do you think will happen? This constant tension of semi-randomized AI, along with dynamic weather for both playable regions, means that each and every main Mission plays out just differently enough to cause new problems to solve. That’s especially true if you put guards on alert status, as they’re constantly looking for you before opening fire, and this makes stealth extra difficult. Some guards even call in armored assault vehicles or gunships, which add all new challenges to making it out alive.

Just describing this makes the game sounds incredibly difficult, but that’s not the case. Patience, at least for the stealth-focused among us, often wins the day. The checkpoints are sparse (so don’t make mistakes), but each death gives you a better sense of Mission progression for the next time. The Phantom Pain, if you want to play the game the way Kojima wants you to play (stealth and speed, if the Mission Rankings mean anything), requires slow observation and patient crawling towards victory. If you almost get caught, Reflex Mode (affectionately called “bullet-time”, at least from my perspective) lets you make a move in slow-motion before detection or death, so even mistakes aren’t always a death sentence. Of course, if you go for the Rambo approach, be prepared to face heavy opposition, but you can plan for this by taking out satellite relays and the electricity (blow it up or turn it off, it’s the same thing). Even so, constant violence seems a reasonable alternative. If you need to change out your whole equipment setup on the fly, you can always call in a supply drop, which costs a little money but goes a long way! While Peace Walker would limit your ammo from Mission to Mission, Metal Gear Solid V’s open world design refuses to limit its player’s options, instead preferring the language of excess. Heck, call a helicopter gunship into the place and kill everybody! While Peace Walker’s Missions often worked with one equipment loadout, The Phantom Pain encourages experimentation at every turn.

Still, any kind of violent approach often gets you nowhere in The Phantom Pain in the long run. Rather, you need tons of soldier recruits to re-build your forces, and it is here that the game takes a turn for the weird and surprising. Quite literally every soldier (even some bosses!) can be recruited in the game, as long as you stun them or put them to sleep. Once you do so, you can take them back to Mother Base via helicopter or, the personal favorite of any one with a pulse, a Fulton Balloon. Originally an innovation of Peace Walker, you attach a balloon to them, which whisks them into the air with an audible yelp, and they “convert” to your cause. Although Fulton isn’t limited to soldiers (you can Fulton a tank, just for example), that will become its primary use since you need to build up Mother Base. I gotta say, the core feedback loop of nonviolence with rewards strikes me as strange and uncommon in the game’s industry, but I’m certainly not complaining!

At the same time, the game quickly introduces the all-important Buddy system. Buddies like D-Horse (yes, a horse), D-Dog (more like a wolf) and Quiet (whom you probably already know from the trailers) allow you to bring different abilities and skills to the table. Think of them like a simplified squad system, which gives you tools to distract, attack, and eliminate enemies. Even D-Horse can, at some point, learn the ability to poop, thereby distracting enemy guards through the power of smell! Quiet, the supernatural sniper (I assume this isn’t a spoiler), does unbalance the game a fair bit at points, but there are reasons for this I’ll get into later. In any event, taking them on Missions and Side Ops developers your bond with them, giving them new abilities and tools to play with. That is, after all, the whole point of recruiting and using anything in this game: to get more stuff. Heck, may as well bring a tank with you too, right? You did Fulton a few, right? Mother Base provides more stuff than even the Fulton system provides through a number of methods.

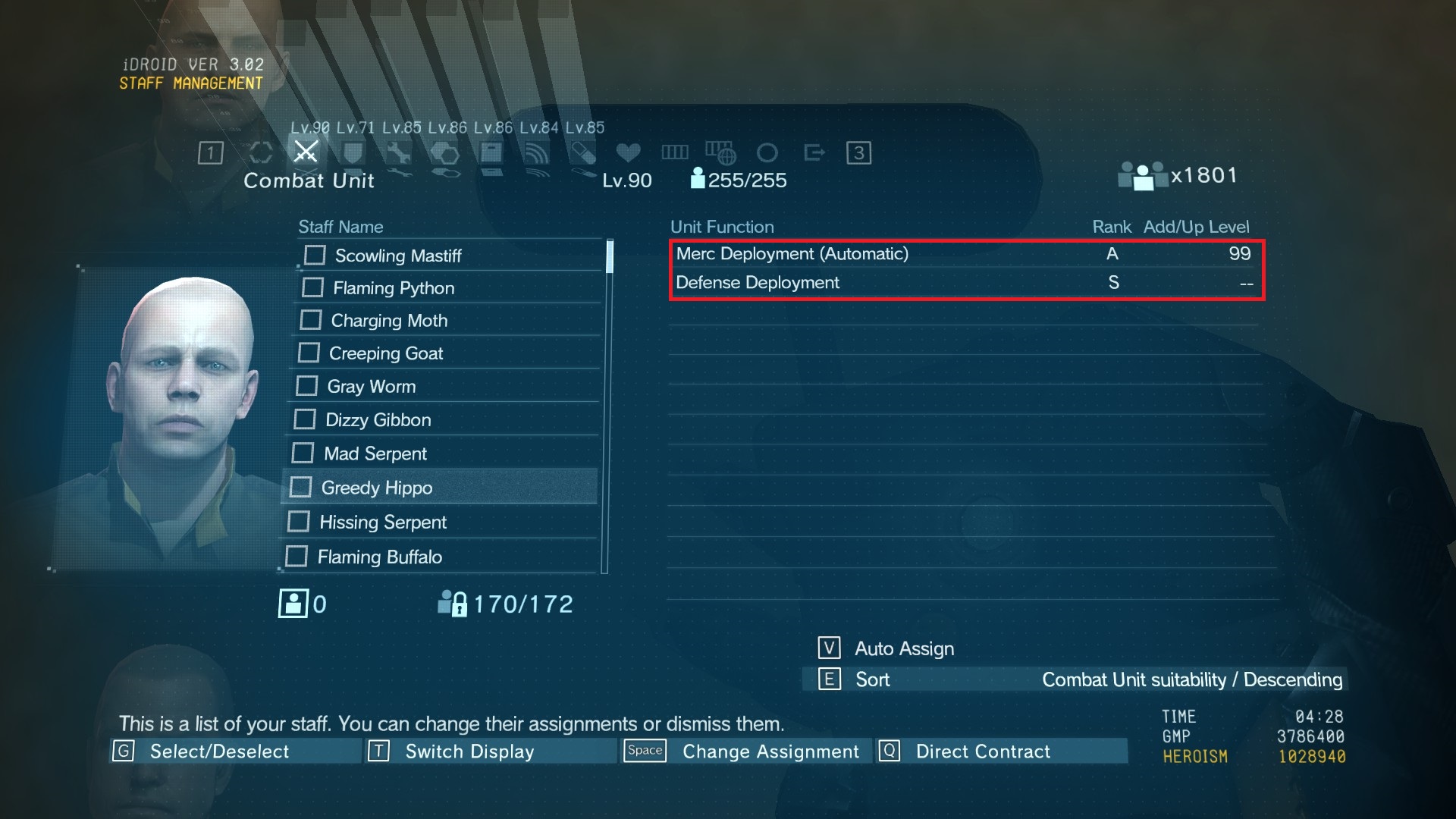

I liken Mother Base’s development to World of WarCraft: Warlords of Draenor: it turns Metal Gear Solid V into a base management simulator in the most abstract way possible (in fact, I’d say somebody at Blizzard played Peace Walker and copied it wholesale). Each solider you recruit from various missions has a particular allotment of statistics and skills, indicated by letter grades for each. These statistics correspond to various functions of Mother Base, from the Combat Team (which you can send out on Missions to get supplies) to Research & Development (which gives you all sort of gadgets and weaponry). Building additional improvements to Mother Base requires a constant influx of money, GMP in the game, and resources, which can be collected in-game, via the Support platform’s auto-generation or taking someone else’s resources in the Forward Operating Base multiplayer aspect of The Phantom Pain. The more platforms you build towards a particular end, the more people you can assign and the higher the level of that platform, allowing new functions to unlock. While you can manually assign soldiers to each platform to correspond to their best stats, the system usually monitors itself quite well through auto-assignment.

Even so, this whole simulation managers to give even time spent a notion of progress. Most anything in the game causes new things to unlock, as does acquiring certain personnel located in certain missions. Research & Development, especially, provides you with a constant incentive to upgrade; the amount of weapons, gadgets, tools, upgrades, and the like is simply staggering in its scope and complexity, from grenade-shooting pistols to the ability to turn yourself invisible. I can’t even begin to detail how much tech lies in this game, but suffice to say it exemplifies Kojima’s constantly playful spirit of game design. If you’re ever played any previous Metal Gear Solid game almost like a toybox, with various ways to mess around with guards and the game itself, then this will be your eternal playground. The water gun is one of my favorites, with its ability to put out fires at night and stun guards with a direct burst to the face. It doubles as a way to make them put down their guns, since it looks like a real one! You’ll find plenty of items that let you play however you want to play, and Mother Base supplements that notion at its core.

Even if you fail repeatedly, Mother Base continues to provide a constant sense of forward momentum, as something always happens. While the process, unfortunately, requires little active participation on your part, it’s a nice gesture that no time in the game ever feels wasted. You’re always accruing something, and you can accelerate the process by going into the open world and gathering materials yourself. You never have to actively do this, however, and that means you can focus on the Main Missions. Some of the upgrades are boring (like Intel, Medical, Support, etc), but they make Mother Base run smoother by each passing upgrade. It starts feeling like an essential part of the game, which is all the more relevant when a story event forces you to make hasty decisions regarding soldier assignments (more on that later).

That was also true of Peace Walker’s Mother Base, which remained just as abstract and strange to use. The previous iteration had most of the same features, and the functioning of Mother Base works in much the same way. Think of The Phantom Pain as merely an extension of that system, with far more fleshed-out results. Metal Gear Solid V often feels like the console equivalent of Peace Walker, but that would also sell things short. Still, as far as abstractions go, the only thing truly different comes from Combat Deployment, which required much more micromanagement on the part of the player in Peace Walker than in The Phantom Pain. In MGSV, you simply send out soldier units to fight with a base percentage chance to get you something; Peace Walker tasked you with finding the best combination of units, soldiers, and equipment for the best results. In some ways, I prefer The Phantom Pain’s streamlined approach, but it does simplify an already-existent system. Given the game’s length, it’s almost a relief not to dive into menus to re-assign units every hour!

And hey, if you want to kill time for upgrades, among other things, the Side Ops have you covered. I liken these to focused time-wasters in the grand tradition of open world games. I remember trying to collect things in Assassin’s Creed II, just for example. The difference, here, is that the innate stealth mechanics of Metal Gear Solid V continues to make even the most mundane tasks fun. Eliminate Heavy Infantry 02? Sure, why not? It’ll give me time to use these new homing rockets, and besides, I can listen to the myriad audio tapes. Even if I need to run a long distance, the tapes really alleviate it by giving me an incentive to simply run through a jungle wilderness. Unlike Peace Walker, the audio tapes are fairly unobtrusive overall, and you don’t need to sit in a menu to listen to them. Even so, they are totally optional, which is a first for Metal Gear exposition. This is part of Kojima’s understanding that Metal Gear Solid V emphasized its open world and the freedom of player control:

There is a degree of freedom, furthermore a MGSness, that is to say there has to be a genuine story. As a last resort, I referred to the organization of TV series. One mission as one story, for example, even missing several episodes (playing out of order), as a series it is similar to the large flow of events being transmitted to the player. The background and character’s detailed establishments and foreshadowing was dispersed and arranged into tapes and codec calls. If necessary to the player, it was made so he or she could actively put together the underplot. The player would not be put on a rail and be able to progress the cinematic story by watching cut scenes all in one gulp after passing a certain point like before. This is because even though the cut scenes has been a selling point before, it has become the main source of the obstruction of freedom.

As such, Metal Gear Solid V proceeds forward at a leisurely pace, not unlike a television series, and you get to decide how much or as little information you learn. The game rarely takes control away from the player in this respect, and Side Ops give you an opportunity to recruit soldiers, relax, explore, and finish the game at your own pace while listening to story bits or awesome 1980s licensed music (hard to beat Take On Me blaring on a helicopter gunship). Plus, Side Ops let you use items and abilities that restrict S-Ranks on main Missions. Want to blow some stuff up with a helicopter, or use that awesome new suit? Go ahead! There’s no penalty! Clearly, Kojima wants you to mess around with all the awesome interactions in the game – why not oblige the poor man!?

Also, did I mention I really like Take on Me?

There are, of course, minor complaints about the game. You might find traversal across the map boring, and that’s perfectly reasonable. I simply liked wandering the map with Quiet, tranquilizing every enemy in sight and taking them to my base for stuff (this is why she is over-powered, at least until soldiers start wearing helmets). It is time-consuming, to be sure, and not every person will like that the environments are densely populated. In a sense, it’s not truly “open world”, since there’s no civilians at all, just centers of tightly focused stealth mechanics. I guess child soldiers count in some way, but they merely present a challenge I already imposed on myself on multiple missions (i.e., don’t kill anyone). As well, Miller and Ocelot tend to talk over the audio tapes if you’re Fultoning or picking up flowers, especially the flowers in the early part of the game – Ocelot, please shut up about medicinal plants, please? Pausing the tapes is a pain, and not at all instantaneous, so be prepared for that constant annoyance. As well, the helicopter takes a LONG time to reach you or drop you off, even upgraded multiple times, and fast-travel (while present via boxes and lifts) is nigh-useless most of the time due to those locations being so sparsely placed.

Honestly, though, these are minor in the grand scheme of things. The core mechanics are so solid, and the structure so enticing, that it creates a near-constant feedback loop of that ever-elusive “fun” that so many games want to become, but never quite achieve. It’s the ultimate stealth sandbox, and I have a good feeling that it won’t be bested any time soon. In fact, you might call the lack of hope for a new Kojima-directed stealth action game of this caliber a “phantom pain” all its own.

Unfortunately, those mechanics come at the cost of a Metal Gear hallmark: boss battles. Due to the structure of the game, it seems Kojima Productions could not design their battles in quite the same way as in previous games. In most video games, boss encounters provide a climax to a section of the game, a new challenge which tests your skills learned up to that point. Given the open structure, and the possibility of myriad upgrades, Kojima Productions clearly could not balance Mother Base’s enormous advantages with its boss encounters. As such, they seem like a relic of an earlier design, rather than a fully fleshed-out feature. I guess it proves how good the core mechanics are that the boss battles aren’t even close to being a highlight. The Phantom Pain, from my point of view, only actually has five boss battles, which we will discuss in turn.

The Quiet boss fight, which ends up in her death by your hands/recruitment, has to be one of the most tense, interesting fights in the whole game. The fight actually jumps on you out of nowhere, since a Side Ops leads you directly to it without any indication she’ll attack. You hear rumors of her throughout the game until this point, and her reputation precedes her, but the massive surprise leaves me delighted. The battle, in effect, becomes a battle of wits between one sniper to another in a wide open arena. This means that Big Boss is at a disadvantage, but stealth can give you the ability to find a good line of sight without letting her shoot you as well. There are, of course, alternative methods to defeating her, but the sniper battle, to me, seems the most exhilarating. She also responds on the fly to various tactics, and learns from your play style (after a few smoke grenades, she started shooting them out of the air). Clearly, they spent a great deal of time choosing the arena and mechanics of this fight, to great effect.

Less can be said about the Skulls. While interesting for plot reasons, the Skulls (mostly the male ones) provide us with the most boring boss fight in the game. Four super soldiers with huge health bars and teleportation abilities chase you and try to kill you. Their move sets are interesting, of course, but the method to their defeat is not: explosions. Literally, that’s it: use tons of rockets or grenades. It’s honestly rather disappointing that you need little in the way of tactics to survive them, and in many cases can run away from them if you’re fast enough. Only two missions ever require you to fight them, and even then all you need to do is find a high perch (which they are too dumb to reach) and fire at them until they die or you die of boredom. You can also use Quiet, which makes them completely trivial (recommended from me, really). The female Skulls present a much more interesting challenge, since 4 snipers is much more challenging than the male Skulls, but even then you can bypass this fight. I’ve done it both ways, and felt nothing lost either way.

As well, you fight The Man on Fire along with The Third Boy, which constitutes one of the worst boss fights in the entire game. I’m not sure why I couldn’t even remember this boss battle when forced to actually write about them due to writing obligation. Maybe it’s because you literally douse him with water, which sounds incredibly dumb and obvious as a strategy. There’s two water towers and a few different options, but this one feels particularly incomplete. Personally, I beat the boss by surviving for 10 minutes, at which point it actually (I kid you not) starts raining, and this is actually the easiest way to beat this boss without dealing with the water towers (or using the Water Pistol). Frankly, The Man on Fire seems like the worst boss fight in the entire game; at least The Skulls present interesting opposition.

Lastly, there is one Metal Gear-related boss fight (also one you do twice), and that battle with the titular beastly robot is alternately interesting and frustrating. You finally reach a wide open area to use all your cool tools. Unfortunately, this fight does not allow you to stealth around in any way, as the Sahelanthropus (that word is said so much) basically finds you wherever you are. And, unsurprisingly, the main way to take it down consists of rockets. While the boss does have weak points, this Metal Gear feels less like a test of wits (think Metal Gear Rex) than a test of patience and supply drop speed due to its massive health pool. Or bring D-Walker. In fact, D-Walker trivializes the male Skulls too, now that I think about it. On Extreme, both the Skulls and Sahelanthropus turn into exercises in tedium since D-Walker becomes a liability due to their speed in getting you out of vehicles.

Interesting, I’m not sure that this avenue could have been avoided. It seems that the lack of interesting boss fights was almost an intentional design choice (or a holdover from Peace Walker, I’m not sure which). Consider that the main villain never appears in one; he is, to put it bluntly, unceremoniously dispatched, and in that sense he’s a very non-traditional antagonist for the series. Peace Walker had better boss battles, even though most of them required the same tactics, due to the Mission structure. The open world design just prevents good boss design in this case, though not much seems lost from my view. Kojima turned a histrionic, cutscene heavy series with extravagant villains that make good boss fights into a low key television series that deals with absence, and that seems reflected in the boss fights themselves.

To understand this sense of absence, we come to the story. As you might expect, to really dig into the meat of the story requires a

SPOILER WARNING FOR THE ENTIRE METAL GEAR SERIES AHEAD. You have been warned.

CHAPTER 2

RACE

Both mechanically AND narratively, The Phantom Pain is rather on-the-nose about its main theme: absence. You could also call it by one of Kojima’s silly theme words “taboo”, and while that’s part of it, translation makes that harder to parse than “absence”. We can think of the latter mechanically in a few senses. First. the game constantly subverts one’s idea of a Metal Gear Solid game. As aptly shown from the preceding discussion, the game directs its mechanics towards almost the exact opposite end of its predecessors, even Peace Walker. In a sense, we could call it a maximalist, confidently wasteful project to the tune of $80 million dollars. Some parts of the game as we received it feel incredibly fleshed out, almost to the point of absurdity. There’s literally almost no end to the list of unlockables and things to do for the casual player. I wrestled with The Phantom Pain for 60 hours, and I still feel like I haven’t done much at all. So many items still remain beyond my grasp, locked behind some Mission with a person I need to take to Mother Base.

On the other hand, the game turns into an incomplete mess somewhere around the 40-50 hour mark, give or take. Story cutscenes seemed shoved into the mix because, I think, they were finished when Konami finally threw their hands up and cut funding for the project. The game repeats Missions, almost treating them like remnants of post-game content that, because they finished it, ended up in the game. Since Metal Gear Solid V has been announced, Kojima seems to have understood the whole debacle as a sort of real-life performance art, as Silent Hills came into being, then was cancelled. The Phantom Pain seems a casualty of his perfectionism, a project that wouldn’t, and couldn’t, ever be finished with any amount of money. Hence, the name seems incredibly fitting in retrospect: the game itself, the experience of playing it, creates this strange absence that, for the vast majority of Metal Gear fans, could not be fulfilled.

The story’s major twist, of course, only twists (haha) the knife. Mission 46, which appears for no discernible reason (even the “unlock True Ending” guides are wrong, and nobody actually knows how it’s unlocked). The game begins with several scenes in a Corsican hospital, as Venom Snake awakes from his coma of 9 years. That same level repeats once more, with the additional revelation that you’re not playing as Big Boss at all. Rather, you play as the anonymous (until this point) medic who stood in front of Big Boss when Paz literally exploded next to the helicopter. This explains a number of things about the game’s progression and design, from the initial “character creation” screen to Venom Snake’s actions during the game. You may have gotten the twist right away, since Kiefer Sutherland voices both Big Bosses and the Medic in the credits, but that still doesn’t make the story surrounding it any less interesting. Kojima also gets to the resolve the fact of two Big Boss characters in the timeline for Metal Gear 1 and 2, which somehow makes logical sense now.

What’s missing from the game is, in a similar way to Metal Gear Solid 2, the protagonist. While in MGS2 Solid Snake is replaced with Raiden, meaning we can never play as the legendary hero, MGSV prevents us from playing Big Boss as he descends into evil and madness. Both games advertised themselves with the unique selling point, and both idolized a particular kind of character in their trailers. In an earlier time, 2001, people wanted to play Solid Snake. People wanted to play a heroic characters with a charming, almost Bond-esque quality who flirts with the ladies and does his job with equal aplomb (barring the occasional soliloquy about finding something to live for, or love blooming on a battlefield). In 2015, however, things strike a very different tone. What’s popular in American culture is the anti-hero, or even the villain, being the person we idolize. Just think of the last few television shows that received critical acclaim; the world appears rather dark and cynical by comparison, even looking at a decade ago.

So, in typical Kojima fashion, Konami advertises a game that promises a path of violence and vengeance for players who want to become The Legendary Soldier Big Boss. Instead, they play a pacifist medic implanted with the memories of Big Boss who acts as his conspicuous surrogate. While the real Big Boss establishes his nation for soldiers to exist and live, Venom “Punished” Snake plays the role of Big Boss thrust upon him by circumstances beyond his control. Unable to remove the demon inside, the evils and memories of Big Boss, he chooses to play along with Big Boss and his grand scheme, for what else can he do? It certainly explains why he smashes the mirror at the end of the game: Venom Snake founds Outer Heaven, and with it forfeits his chance at a normal life of his own. Forever will he be swallowed up into the legend of Big Boss, unable to live his life as himself. That’s a phantom pain if I’ve ever seen one: the absence of your own personality.

Why are we still here? Just to suffer? Every night, I can feel my leg… and my arm… even my fingers. The body I’ve lost… the comrades I’ve lost… won’t stop hurting… It’s like they’re all still there. You feel it, too, don’t you? I’m gonna make them give back our past.”

– Kazuhira Miller

That applies to many characters in the game, each of which thematically shows how vengeance, pain, and misguided intentions come from loss. Kazuhira Miller thinks nothing except revenge since the moment he loses his actual arm and leg from Skull Face’s plan; Revolver Ocelot, we assume, feels much the same. Code Talker loses his national culture through the subtle genocide of the Navajo through re-education camps; his chance at “revenge” turns into the vocal chord parasites which become the central focus of the story, a far greater evil than that perpetuated by white society (he also cannot eat for sustenance due to the parasites, which is an important notion in Navajo culture). Skull Face experiences his own phantom pain through the loss of his face, his family, his nation, and (most especially) his original tongue. His origin story explains in great detail why he wants to destroy English, the lingua franca which stole everything from him.

I was born in a small village. I was still a child when we were raided by soldiers. Foreign soldiers. Torn from my elders I was made to speak their language. With each new post my masters changed. Along with the words they made me speak. With each change, I changed too. My thoughts, personality, how I saw right and wrong. Words can kill.

– Skull Face

The same goes for The Third Boy, Psycho Mantis, and the Man on Fire, Volgin, who only know pain and suffering, seeking to perpetuate violence towards anyone they please. Even Eli, later known as Liquid Snake, feels constant resentment as he will never be as great as his “father” Big Boss. Almost every character perceives their suffering, and acts according to that suffering in ways which lash out into the world. Anger becomes a motivation, subsequently transformed into vengeance, which changes the people who see things in this lens. Skull Face and Venom Snake are both tools of Zero and Big Boss, respectively; both are the “sins of the father”, if you want to think of it that way, and both are intended to stoke the fuels of conflict, or eliminate it entirely. The experiences they share scar them both. Not surprisingly, one of the first Phantom Pain trailers used this apt quote by Mark Twain:

Anger is an acid that can do more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything on which it is poured.

– Mark Twain

I think we can say, definitively, that vengeance is never the answer (never mind the myriad Bible verses that state this directly). The cycle of violence continues indefinitely, and any attempt to fill the void with revenge only makes the hole inside larger; by going for vengeance, they lose everything And yet, this is not the only option Kojima allows his characters. While quoting Friedrich Nietzsche seems a bit cheesy when it happens, there’s probably no quote more relevant to the “meaning” of The Phantom Pain’s story than this one:

There are no facts, only interpretations.

– Friedrich Nietzsche

Think of it in this sense: Kojima provides the player with a particular framing device for viewing the events of The Phantom Pain. Venom Snake, and we as the player by association, are unreliable narrators. We are meant to think of ourselves as Big Boss, that our actions are that of a dictator who wants to fulfill The Boss’ Will (not correctly, of course) by creating a nation for soldiers. Thus, we see Venom Snake’s quest as one of complete and total vengeance. And yet, that character does not appear at all in The Phantom Pain. Sure, Venom Snake feels the loss of his limb, his personality, his self, but peeks into his psyche break through in his actions. While Big Boss often talked often, with witty one-liners throughout, Venom Snake seems more reserved, and more likely to consider both sides of the case than simply to take action. We can see this when the protagonist reacts to Huey’s betrayal, along with killing his lover (possibly wife?) Dr. Strangelove. Rather than murder him in cold blood, Venom Snake simply exiles the man from Mother Base; Huey must live with his actions, rather than be killed in denial of truth.

When given the task to kill the soldiers under his command infected with the vocal parasites, Venom Snake does so unwillingly and at great personal cost. Big Boss forced him into these actions, to make him a demon, but Venom Snake refuses to be complicit in the never-ending cycle of revenge. Venom Snake inherits the memories, actions, and (at times, especially with Paz) guilt of Big Boss’ memory, but refuses to respond to them in a way that continues conflict. Even so, you are never really the Big Boss, and that’s definitely intentional. You’re living the dream of being Big Boss – but not the reality.

It is just a dream. It is all a dream. I am in it, and you are in it too. I am the dreamer, but you are having my dream. Do you get it now? You do, don’t you? Peace Day never came…Our wishes do not come true. We just cling on to our dreams, our phantoms. Mine and yours.

– Paz

This happens throughout the game, in various circumstances where we assumed, via the trailers, that Big Boss would become the vengeful dictator that we assumed. When given a job to kill a group of child soldiers, Venom Snake instead fakes the video tape and saves the kids. When given the opportunity to kill Eli many times, who surely planned an insurrection, among other things, Venom Snake refuses (even in the scrapped Mission 51, Venom Snake accidentally shoots Eli, and is devastated until he finds out the kid was wearing a bullet-proof vest). Heck, he even tells Miller that he wants to educate these kids, and show them a life that isn’t “behind the gun”. This is the antithesis of Big Boss’ goal, which in Metal Gear 2 involves constant conflict. Interestingly, in Zanzibar, little kids are all over the base, all of which are currently unarmed. Big Boss plans to turn them into child soldiers:

You saw those children didn’t you? Everyone of them is a victim of war somewhere in the world and they’ll make fine soldiers in the next war. Start a war, fan it’s flames, then create victims … Then save them, train them… And feed them back onto the battlefield. It’s perfectly logical system. In this world of ours conflict never ends, and neither does our purpose, our … raison d’être

Venom Snake can kill Quiet early in the game; most players, I suspect, will let her live. Think of this as the inverse of the shooting at the end of Metal Gear Solid 3; while in that game, we are forced to be complicit in the death of The Boss, thereby setting up an emotional gut punch, here Venom Snake lets the player make that decision. Rather than scene, which told us wars and conflicts are determined by the politics of “the time” (hence The Boss needing to die), here we interpret The Boss’ Will for ourselves. Do you choose to spare a life, or take one? Do you take revenge even on those only indirectly responsible for that revenge? If Quiet lives, she becomes one of your most trusted companions through actually playing the game, despite her inability to speak English due to vocal parasites. Venom Snake’s compassionate actions to seemingly all and sundry (he doesn’t even kill Skull Face!) convince her that revenge may not be the answer she thought. Even as the soldiers on Mother Base fear and hate her, she somehow doesn’t kill anybody, and willingly remains a prisoner (she can escape at any time, as we find out pretty early); heck, she even gets tortured on Mother Base, and still does nothing. Her true role, as we find out, was to infect Mother Base with the vocal parasite in case all other options failed, and yet she chooses not to do so:

Venom Snake’s actions, and by association the player’s actions, make Quiet into one of the most interesting, fully fleshed-out characters in the series. And yet, I imagine most people will judge her at face value for the ridiculous (well, not really for Kojima, considering NANOMACHINES SON) outfit. Not surprisingly, that outfit caused a great deal of controversy among some sections of the Internet, which totally played into Kojima’s hands. The director knew people would interpret her appearance in a particular way, as we the player do throughout the game, and completely proved his point.

I know there’s people concerning about ‘Quiet’ but don’t worry. I created her character as an antithesis to the women characters appeared in the past fighting game who are excessively exposed. ‘Quiet’ who doesn’t have a word will be teased in the story as well. But once you recognize the secret reason for her exposure, you will feel ashamed of your words & deeds. The response of ‘Quiet’ disclosure few days ago incited by the net is exactly what ‘MGSV’ itself is.

I’m not sure if Kojima himself has been familiar with the discussion of sexism in regards to video games, but we must assume he’s familiar with it on some level. Nearly every thing in this game, from the outside, can be interpreted entirely differently until we actually play it. Easy answers mislead; quick hot take judgments often bring us to the wrong conclusions. The way we interpret events can change the way we act. The way we speak, the ideologies we accept, and the beliefs we exemplify can be used for good or ill. Our assumptions or presuppositions can lead to all sorts of self-deception, and lead us to wherever we want to go. The absolutes and constant bickering of the modern world are exactly what lead to continual conflicts, rather than solutions. In another phrasing, words can kill.

Instead, the player, you, is free to interpret the game’s events in your own light. The revelation at the end of the game exists specifically to point towards that view. You now share in the story of The Legendary Soldier, Big Boss, and your actions directly contribute to it. But, if you choose, you may act in a completely different way than the Big Boss you know. I did, certainly, as The Phantom Pain encouraged me to play as a complete pacifist for most of the game. It allows us to play a AAA video game release in a predominantly Christian way by allowing us to interpret the actions of Venom Snake in the way we see fit. The moment-to-moment emergent narrative of actually playing Metal Gear Solid V lets you see it as a vehicle of revenge, or as a pacifist playing the role of Big Boss.

But Kojima really doesn’t leave this up to interpretation, does he? I would say this is his most personal game to date, much more an exemplification of his personal life philosophy than any game subsequent to it. He clearly wanted us to play it in this manner, and subsequently enjoy it no matter what. It’s both a subtle nod to player agency and a big old “thank you” for playing his Metal Gear games for 28 years. Venom Snake is clearly the opposite of Big Boss, intended to (like Solid Snake before him) bring about The Boss’ will without actually knowing what it is. I think that, to me, tells you more about The Phantom Pain than anything else: that the interpretation of even the greatest intentions can have dire affects on the future, creating endless pain. And the only way to stop it, is to resist it.

Enemies change along with the times, and the flow of the ages. And we soldiers are forced to play along… I didn’t raise you and shape you into the man you are today just so we could face each other in battle. A soldier’s skills aren’t meant to be used to hurt friends. So then what is an enemy? Is there such thing as an absolute timeless enemy? There is no such thing and never has been. And the reason is that our enemies are human beings like us. They can only be our enemies in relative terms. The world must be made whole again…No East, no West, no Cold War. And the irony of it is, the United States and the Soviet Union are spending billions on their space programs and the missile race only to arrive at the same conclusion. In the 21st century everyone will be able to see that we are all just inhabitants of a little celestial body called Earth. A world without communism and capitalism…that is the world I wanted to see.

In a way, it’s not surprising that Big Boss chooses to call himself “Ishmael” during the introductory sequence. Ishmael, in Moby Dick, is only a minor participant in the actual events of the novel. However, his first-person narration recalls the events of Ahab’s crew, who meet the dreaded white whale. Both Ishmael and Ahab interpret the whale in a different way; Ahab sees the whale as an evil force, meant to bring harm and destruction (to him personally, most of all), but Ishmael sees things differently. His fascination with the whale comes strictly from an open mind, and we should assume Big Boss fashions himself as the narrator of the “great legend” of himself who crafts the real tale. Unfortunately, the real Ishmael is the story of rejection, abandonment, and isolation.

That isn’t dissimilar from Herman Melville’s own experience. It’s also telling that Moby Dick wasn’t always heralded as a classic of English literature in its initial release. Critics panned it, in part due to its missing epilogue that filled in numerous plot-holes which were missing in the first printing (if this is starting to sound really on point regarding Metal Gear Solid V…). Herman Melville only earned about $500-600 from the first printing, and in his contemporaries completely sank his career due to these printing mishaps. His career never “took off”, as it were, and he eventually died poor.

Perhaps Melville didn’t use the name in that exact way, but “Call me Ishmael” in the novel is meant to signify the first person narrator’s presence as well as allude to the birth and salvation of Ishmael in the Bible. Ishmael is the result of Sarai’s lack of faith. Because God leaves Sarai barren, unable to have children, the wife of Abram does not take this lying down. Instead of following God’s will, she takes matter into her own hands, as we see in Genesis 16:

Now Sarai, Abram’s wife had borne him no children, and she had an Egyptian maid whose name was Hagar. 2 So Sarai said to Abram, “Now behold, the Lord has prevented me from bearing children. Please go in to my maid; perhaps I will obtain children through her.” And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai. 3 After Abram had lived ten years in the land of Canaan, Abram’s wife Sarai took Hagar the Egyptian, her maid, and gave her to her husband Abram as his wife. 4 He went in to Hagar, and she conceived; and when she saw that she had conceived, her mistress was despised in her sight.

Sarai’s lack of faith leads to Abram conceiving a child. This is, as we might imagine, exactly what Sarai wants – instead, she feels vengeance and hate towards her perceived “rival”.

5 And Sarai said to Abram, “May the wrong done me be upon you. I gave my maid into your arms, but when she saw that she had conceived, I was despised in her sight. May the Lord judge between you and me.” 6 But Abram said to Sarai, “Behold, your maid is in your power; do to her what is good in your sight.” So Sarai treated her harshly, and she fled from her presence.

Hagar is abused by Sarai, enough so that she flees. I shudder to think what, exactly, happened in that instance, but it certainly could not be pleasant. If a pregnant women is fearful enough to run away from her husband and captivity within a culture of almost no support for single women, you better believe “harshly” gives us a ton of subtext! Without hope for survival, she runs to protect her child, and things don’t bode too well for her. That is, until she meets an angel:

7 Now the angel of the Lord found her by a spring of water in the wilderness, by the spring on the way to Shur. 8 He said, “Hagar, Sarai’s maid, where have you come from and where are you going?” And she said, “I am fleeing from the presence of my mistress Sarai.” 9 Then the angel of the Lord said to her, “Return to your mistress, and submit yourself to her authority.” 10 Moreover, the angel of the Lord said to her, “I will greatly multiply your descendants so that they will be too many to count.” 11 The angel of the Lord said to her further,

“Behold, you are with child,

And you will bear a son;

And you shall call his name Ishmael,

Because the Lord has given heed to your affliction.

12 “He will be a wild donkey of a man,

His hand will be against everyone,

And everyone’s hand will be against him;

And he will live to the east of all his brothers.”

Whatever the real world interpretations of this story, it holds interesting relevance to the story of Big Boss. Ishmael is an exile not by birth, but because of the actions that led to his conception. Sarai’s actions led directly to his existence. And, according to the story, while Hagar’s child will conceive many descendants, he will also be a man that generates constant conflict, This is both a blessing and a curse in equal measure. Interestingly, the story of Ishmael resolves in Genesis 21 with the exact same exile, only with the possibility of Ishmael dying of starvation in the wilderness. In the end, there is no real resolution to the story: Ishmael’s fate is surrounded by external forces, and he can never break away from his fate or destiny as an opposition force to the true covenant child, Issac (this probably explains why Christian evangelicals think that Ishmael is where Arabs came from, but I digress heavily right here…).

Big Boss misses the real meaning of the name he calls himself. Those three lines tell us to interpret the story in the same manner as Ishmael’s exile and miraculous survival. But Big Boss is only a dud by comparison, a man who comes to represent some horrible things who later regrets those terrible things. He wasn’t the narrator at all; his ideals were dictated by fate and outside forces. That legend leaves him as nothing but a broken man at the end of Metal Gear Solid 4, who finally understands that his actions were all the things The Boss was against. He ended up trapped in the same never-ending cycle, endlessly obsessed with the very things he sought to avoid. He was really Ahab, and his actions came at a great cost. Some of his final words to his “son”, Solid Snake, tell the story:

It’s not about changing the world. It’s about doing our best to leave the world the way it is. It’s about respecting the will of others and believing in your own. […] Zero and I… Liquid and Solidus… We all fought a long, bloody war for our liberty to free ourselves from systems, nations, norms and ages, but no matter how hard we fought, the only liberty we found was on the inside, trapped within those limits… The Boss and I may have taken different paths but in the end, we were both trapped inside the same cage… “Liberty.” But you have been given freedom. Freedom to be… Outside.

This is, more than likely, Kojima’s message to the player. The way that you think does have a real-world effect, and you are not above being taken by its promises of being “right”. The manner in which you respond to your “phantom pain” is what remains the most important; how you see those events will tell you a lot about yourself, and how you can change. The framing you give your past – whether to let it define you, or for you to define it, will most certainly induce certain actions on your part. Interpretations can change things more than we can imagine, and we must sift through the lies that constantly shuffle through our point of view.

Honestly, it seemed like Kojima had enough of the series with Metal Gear Solid 4, its endless cutscenes and tying up loose ends. Why should this strange period in Metal Gear Solid history be the final game in the series, at least of the ones directed by Kojima? Mostly, it seems, because Kojima knows fans will never stop demanding for a new story in this series. As such, we are left with a message instead: to find the real truth for ourselves, and to stop clinging to the story. Rather, seek the meaning behind the story, and not just endless interpretation. We are prone to confirmation bias, and the Internet only makes this easier. Search for the truth first, and then seek to change things, rather than making a hasty judgment. Could there be a more fundamentally Christian message than that?

7 “Do not judge so that you will not be judged. 2 For in the way you judge, you will be judged; and [a]by your standard of measure, it will be measured to you.3 Why do you look at the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?

– Matthew 7

And with that, the story of Big Boss fades into the smoke of legend, to forever become a strange, inexplicable myth that can’t be understood fully, as human beings can never be fully understood in their innermost parts. The fans want none of that; they want to be told exactly how things happened, or why Big Boss turned “into a villain”, or some very distinct plot points regarding how it happened. And yet, they’ll never resolve this. Kojima always paints his characters in shades of gray, not black and white; the truth is difficult to reach, and it cannot emerge via simplistic explanations. All of the information, clearly, remains there, and yet this seemingly “unfinished” game really jerks with people’s emotions. They feel a mechanical “phantom pain”, because there’s no more Metal Gear Solid to play, and no more hope that we’ll ever see the descent of Big Boss. But did that ever really happen? Or was this merely a myth we conjured? Maybe it was all a dream…

Never Be Game Over, indeed.

Addendum

That said, the plot does falter on a few points which I would be remiss in mentioning. For one, I’m not exactly sure why Quiet can’t communicate with anyone via the magic of the written word or speaking a language other than Navajo. When they interrogate her, they keep using English. It’s clear she understands English, but can’t speak it…so why wouldn’t Kazuhira Miller try Japanese? In the iDroid, we know every solider on Mother Base speaks multiple languages, so this shouldn’t be a big deal to try every language. Heck, ask Code Talker if she can speak Navajo! Or just have her write it down! Seriously, I don’t understand this part; given that the game places such an emphasis on language (even to the point where Kikongo becomes a major problem for the player in their Mother Base), the whole circumstances surrounding her interrogation fail to make sense. It does lend credence to the theory that the game came out in an unfinished state.

But, I’m guessing it was intentional, and so I think we can just say that this is a minor point in the grand scheme of things, especially if we consider “interpretation”, and whether or not Quiet wanted to say anything at all. Maybe she wouldn’t have talked to anyone anyway, for all we know. There I go, speculating again…