Metagames as Dogmas

What struck me as interesting about the whole concept derives from its incredibly similarity to actual belief frameworks. A few people turn into trendsetters, and the rest follow them due to the desire to win. Whether or not they become false prophets or not, the very hope of providing for the best winning strategy often draws people to particular personalities and strategies in excess (i.e., a ton of people pick a characters because he’s overpowered, or a particular build order due to its guaranteed efficiency). In time, that strategy will fade, but it gives them a temporary hope that they will win…or, at least, they will win easier.

In a way, it is very misleading to suggest one optimal strategy rules them all, and yet that is often the way you see it said by the supposed “experts” of a game. I can accept such talk once the game hits a consistent level where you see the same thing win repeatedly (StarCraft II’s deathball, MvC3’s continual use of Dr. Doom, Vergil, Zero, and probably one other outlier every once and a while). Before that, though? The game isn’t given time to develop organically, mostly due to the constant communication between parties. That leads to the prevalence of complete overuse of an idea (Face Hunter), which then leads to a host of counter ideas which utterly crush it (control decks).

And this is why I call the “metagame” more an “interpretation” than anything else. Given the vast array of variables, judging something as “weak” depends entirely upon one’s own experience and ideals from the start. A “metagame” demands that you accept the definition of others for “true success” within a given set of rules, because there’s no other way to play the game. Once you accept a certain set of platitudes, then experimentation dissipates; boring routine sets in, and a game can become boring quite quickly. New ideas must flow, or else the stream will dry up and leave a very boring game in its wake (note to developers: please don’t let this happen to your games!). The moment a game system turns into dogmatic adherence to certain ideas in exclusion, you know it’s time to jump ship.

Theological Metagames

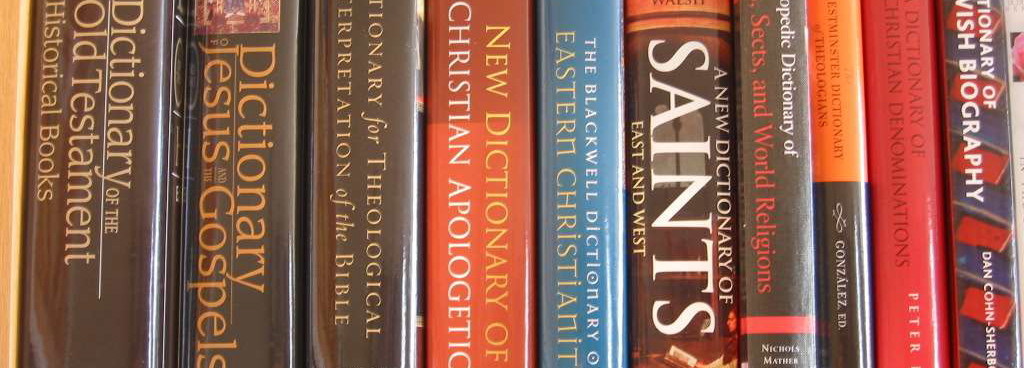

That also follows for my own experience of what theology contains. We return to Wikipedia, once again, to give us a common sense idea of what theology means in the public eye:

Theology is the systematic and rational study of concepts of God and of the nature of religious ideas, but can also mean the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university, seminary, or school of divinity.

Surprisingly, the concept seems quite basic – why, it’s just the systematic and rational study of God! However, that simplifies things a bit. For one thing, just look at all the assumptions inherent in the text above. Some theologies intentionally avoid systematics, because they do not believe God as a concept and as a self-existent thing can be defined by human categories. “Rationality” implies a study of God using logical processes, but logic (if used at all) exists as a tool for the purpose of studying God. Rationality, far as I know, does not play a role in every theological study for it, in some ways, denies the basic human emotional needs and wants that form the core of religious identity. In other word, a logical reduction does not quite get at the thing.

Is religion a set of “ideas”? In a sense, yes…but in another sense, no. Some would categorize religion as the rational assent to a general set of principles, ideas, thoughts, and things. It might represent a systematic understanding of those ideas, and possibly not. You might not be able to understand some of the concepts in full (the Trinity comes to mind), but you nonetheless accept them in the best possible sense a human being could apprehend such knowledge. Furthermore, some theologies completely reject any ideas similar to any of the aforementioned tools; for some, simple acceptance of a few key dictates works fine for them. Complexity and simplicity co-exist in the theological realms; some of the most complex theological discourse can be summed up neatly. Theology writers may write complex things to act simply; sometimes, actions speak of a greater theology than a long, drawn out volume devoted to infinitesimal minute details. By comparison, video games and their associated metagames are almost trifling in their simplicity.

In other words, what I mean is that theology varies. It is a complex subject, filled with tons of different opinions that generally revolve around the locus of Christianity and (for most, I assume) the Bible (along with some books added or removed, give or take). While it is related to Christianity in many ways, that also does not make it the thing itself, nor a thing in and of itself. It simply seeks to categorize what Christianity should be. In effect, it is an argument, not even necessarily of a logical kind, to which one stands in opposition to other kinds of ideas regarding faith and life. Think of it as a competition – everybody’s got the right answers, if only everybody else would agree with them! Hence, Christian disunity, division, and all other manner of unsavory things arise.

None of this assumes an absence of absolute truth or the very idea suddenly dissipates; rather, I mean the tendency to let our pride suddenly turn a lack of clarity into the clearest of ideas. “How could you read it any other way?”, you might wonder, at somebody who just doesn’t agree with you. Pride can enter the picture very easily when we imagine ourselves as the vehicle for all truth, and not just a piece of it. That’s when things turn sour.