Last updated on March 4, 2013

OR: Ancient Land of Ys-rael

I did not grow up on the Ys series. I did, however, grow up listening to Contemporary Christian Music (CCM). I can’t stand 99% of what’s being produced today, though I still have a soft spot in my heart for ’90s and early-early ’00s CCM (before the “let’s only do worship music” fad went full-swing).

However, I can stomach the occasional Casting Crowns song, because they deal well with subjects near and dear to my heart. Even with that Mac Powell-ish voice, even with a lingering subtext that the right slogans will save us, they still take on issues of grace vs. works, various hypocrisies within the American Christian church and culture, etc. They’re the closest thing to honest lyrics I’ve seen since every Five Iron Frenzy song ever. Take, for example, “Jesus, Friend of Sinners” —

Jesus, friend of sinners, we have strayed so far away

We cut down people in your name but the sword was never ours to swing

Jesus, friend of sinners, the truth’s become so hard to see

The world is on their way to You but they’re tripping over me

Always looking around but never looking up I’m so double minded

A plank eyed saint with dirty hands and a heart dividedOh Jesus, friend of sinners

Open our eyes to the world at the end of our pointing fingers

Let our hearts be led by mercy

Help us reach with open hearts and open doors

Oh Jesus, friend of sinners, break our hearts for what breaks yoursJesus, friend of sinners, the one who’s writing in the sand

Made the righteous turn away and the stones fall from their hands

Help us to remember we are all the least of these

Let the memory of Your mercy bring Your people to their knees

Nobody knows what we’re for only what we’re against when we judge the wounded

What if we put down our signs crossed over the lines and loved like You didOh Jesus, friend of sinners

Open our eyes to world at the end of our pointing fingers

Let our hearts be led by mercy

Help us reach with open hearts and open doors

Oh Jesus, friend of sinners, break our hearts for what breaks yoursYou love every lost cause; you reach for the outcast

For the leper and the lame; they’re the reason that You came

Lord I was that lost cause and I was the outcast

But you died for sinners just like me, a grateful leper at Your feet

That, right there, is a pretty good song. Honest, solid lyrics.

Anyway, what does this have to do with Ys? I’ll get there, I promise. But first, I have to quickly introduce some important ideas and concepts into the discussion, or it won’t make sense.

First: fitting the Christian (meta)narrative into video games is difficult, if not impossible. At the very least, it doesn’t jive with fantasy RPGs, anything with swinging swords and slaying demons, or even things with solving complex puzzles. If you’re in the business of epic world-saving, you can’t do it very well in the Christian framework. Why? Because everything of ultimate importance that needs to be accomplished, has already been accomplished by Christ on the cross. I’m not saying “there’s nothing for humanity left to do,” but something that fits into a cool story about a hero saving the day? Not really. Heck, even Left Behind’s authors had to recognize that, and it was working with shifty eschatology from the start. And, in my opinion, they’re also terrible books that engender even more terrible ideas (see the Left Behind RTS where you gun down “secularists” and “rock musicians”).

Second: among other religions that claim monotheism, Christianity is in a strange place. We Christians call the trinity “a mystery.” But Jews and Muslims alike look at the trinity and say “that’s just some weird variant of polytheism.” But here’s the idea: three distinct entities that are, simultaneously, one entity. “The godhead.” Father, Son, Holy Spirit. The really important theological distinction about this is that it tosses out the window the following explanation for why God would bother making the universe, or any other creatures with sentience/agency: “God was lonely.”

The Christian view of the divine says that God was, before the existence of anything else, already in a perfect harmonious relationship: Father Son and Holy Spirit talked and knew and experienced one another fully. There’s also the whole matter of “other” supernatural beings (angels, fallen angels, etc) … keep that in mind as well. Because now I’m going to talk about Ys.

The mythology of Ys, like many JRPGs, is a variant on Judeo-Christian Genesis. Some of this was determined from the beginning (1986), much of it was retconned in the last decade.

But here’s how it goes: God creates everything. God sees humans acting like idiots. God calls for the Noah/flood solution (hint: “Ys VI: The Ark of Napishtim” is a reference to Utnapishtim, the Noah figure in the Epic of Gilgamesh). God’s angels beg that this not happen, and are as such cast out. Two of said angels are Feena and Reah, who become the “goddesses” of Ys. Much of the others are the beings known through the rest of the series as “darklings.”

(Ys fans, feel free to correct me on this, but having played every English-language game in the series to date, this is what I have so far.)

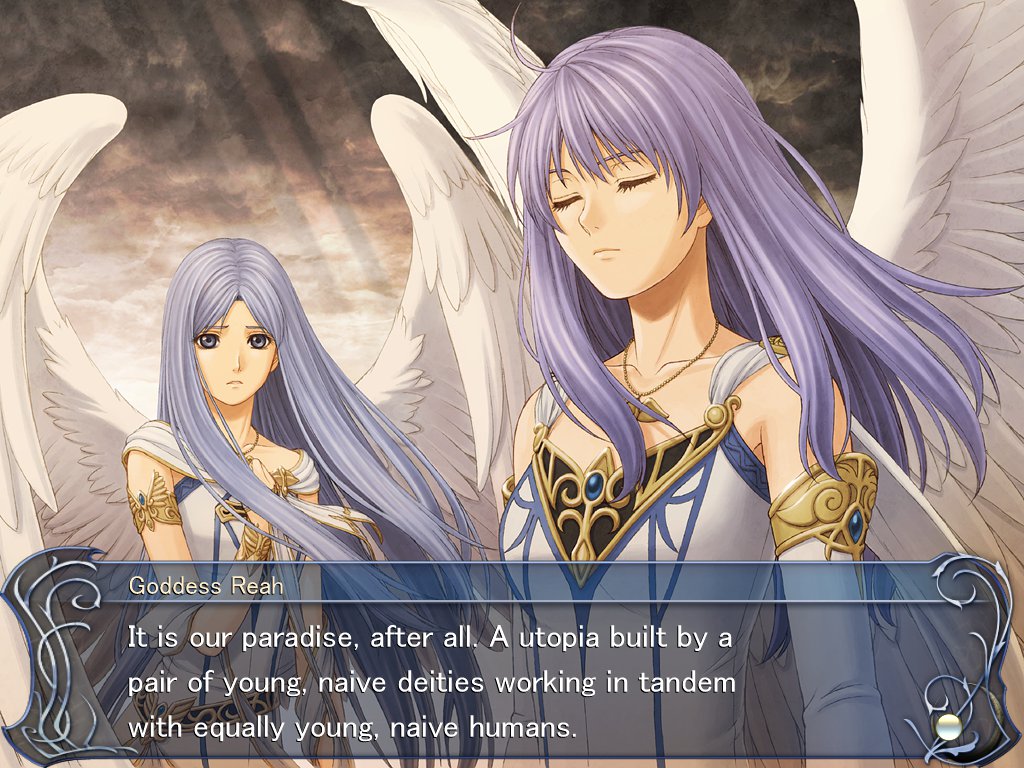

So what’s important here? The civilization of Ys is brought about through the power of fallen angels who care for humanity. They are non-omni. These types of deity make for the more interesting stories, as there’s plenty at risk. This quote, from the third prologue for Ys Origin, summarizes a lot:

They use the power of an artifact called the Black Pearl (also known as the MacGuffin of ultimate power in this man’s mind). It’s the power used to bring prosperity to the people of Ys; it also attracts the darklings and taints the people with greed. That is the power used to send Ys into the sky, making it a floating continent, leading to the conflict in Ys Origin.

For Feena and Reah, their choice to bring prosperity to this one bit of land and its people among the entire world is akin to having a “chosen people.” Before Judaism became categorized as a world religion, it looked a heck of a lot like a tribal religion. The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob was vying for the heart and souls of many, but the starting point (quick, turn to Genesis 12!) is the people of Israel. And for Feena and Reah, it’s … the people of Ys-rael?! (Editor’s note: I don’t endorse the use of horrible puns, but this one was so horrific that it was an exception.)

Again, there’s a key difference in the construction of the Ys universe and the Judeo-Christian worldview. It only allows for two views of God. For the first, man is still subject to the wrath of the true creator God. Galbalan, the final boss in Ys III, represents this wrath, sent to wreak havoc according to the will of the divine. For the second, the true creator God is apathetic, and man is left to fend for himself among a host of powerful-but-not-omnipotent, wise-but-not-omniscient, deities.

And when Feena and Reah (spoiler) seal away the power of the Black Pearl in Ys Origin, and they lose their wings (which eventually grow back), they do literally depart and their power is lost to the people. This sort of benevolent but not powerful (enough) deity is quite common in JRPGs, especially for female deities. It makes for endings and epilogues that sound a lot like modern deism: “God made this, but let’s move on, it’s up to man to forge a path forward.” Outside of Ys, see the LUNAR franchise as another great example. Heck, another Game Arts studio game (Grandia) does much the same thing.

I’ll say it again: the good, omniscient/omnipresent/omnibenevolent God of Judeo-Christianity can almost never fit within the realm of epic fantasy RPGs because that leaves the player with too little to do that would feel satisfying. The myth needs to be changed so that good and evil are at odds and the stakes are high, and YOUR actions as a mortal hero make the difference. It makes for a cool story and a nice feeling, but certainly doesn’t present reality.

Feena and Reah (esp as depicted in Ys Origin and the I&II Chronicles PSP games) remind me of a “buddy Christ” Jesus, but without the tongue-and-cheekness that goes with that term (Editor’s note: Insert “Jesus is my boyfriend” CCM joke here). It’s an intimate portrait, something to which you can relate and drawn close – excellent work on Falcom’s part. They are beings that make a sacrifice: “my wings are gone and I am so free; nothing to weigh me down.” And we know that sacrifice is a key theme in — which religion was that? — oh right, pretty much all of them. And yes, there were “Christ figures” long before Jesus Christ walked the earth in different stories, and there were even the Roman & Eastern mystery cults that would focus on a divine being who took the suffering meant for mankind. In those stories, that being would tend to disappear. For Feena and Reah, they go dormant for awhile before they have to yet again seal the power of the Black Pearl (a manifestation of mankind’s “sins” …?). In the Christian story, Jesus wins: fully divine and fully human at the same time, He takes the pain and the wrath and comes out resurrected, re-alive.

If there is any Japanese game in recent memory that dared suggest we can have our cake and eat it too, I look to Final Fantasy X and X-2. Hey, call me crazy. And yes, I know there’s no Christ figure there. But that scene at the climax of FFX’s story, when Yuna says she refuses to fall into the cycle of sacrifice and hope for another summoner to do the same thing over and over and find a way to break “the cycle of Sin” … well, that sounds like what happens in the Gospels to me. And they did it with divine assistance (the Fayth). AND the one person who was lost as a result, the (literal) dream-man who appeared outside his stable environment, Tidus … get the “true ending” in X-2, and see him re-dreamt into being. See him resurrected.

But Feena and Reah? They’re beautiful, wonderful pictures of divine love, but not so much on the power. They need Yunica Tovah and the Fact brothers in one scenario, and they need Adol and Dogi in another scenario. They are as lost as we are, but it’s a fun adventure (if all goes well) solving the problems of our ancestors and moving forward.

Do you see the differences, the tensions? Okay, good. That’s all I was trying to do.