Last updated on June 17, 2014

With this year marking the 60 year anniversary of the publishing of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, I think it’s appropriate to take a look at Tolkien’s philosophy of fantasy.

In his “On Fairy Stories”, Tolkien lays out his methodology for creating what he calls “secondary worlds” . He sought to defend fairy stories as both a method of escapism, and as a way to gain new perspective on the real world through the lens of an imaginary one (which he refers to as “recovery”).

Tolkien was quick to staunchly refute the common label of “allegory” for these stories. While allegory has hidden meaning that often tries to prove a point, “fairy stories”, as Tolkien saw them, found their point in perspective. It wasn’t that the story itself had a point to prove about the reader’s life. The story simply gave the reader the perspective of life within its own system of laws. The “point” of such stories is entirely the reader’s to find. While one reader walks away from The Hobbit with the lesson of finding the extraordinary in the extremely ordinary, another may come away with the lesson in trusting to the fellowship of friends to finish something you start. Both are valid truths to be taken from the text, as both come from the reader’s perspective. In Tolkien’s words in the preface to The Fellowship of the Ring,

I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.

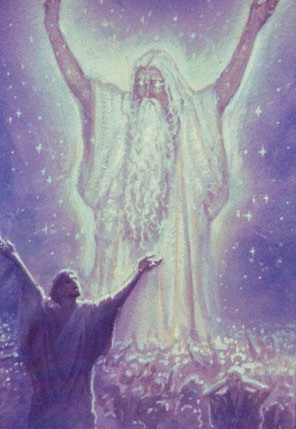

What was most important to Tolkien, and what he claims sets true fairy stories apart from dream stories or beast tales, was a consistent framework. Everything that happens in the imaginary realm happens because it is consistent with the wholly separate and alien set of laws which govern it. For instance, in the Lord of the Rings, elves are immortal not because of some mysterious and magical power they possess. Rather, the internal laws of Middle Earth are such that the Elves were created this way by Illuvatar, the supreme deity of Middle-earth.

Consistency set Tolkien apart from those that came before him and set the stage for every major fantasy work that would follow it. Tolkien’s attention to detail is extraordinary. He created several new languages based on real life inspirations; by all accounts his elvish language of “Quenya” were influenced largely by Finnish. He established histories for every race, character, and part of Middle Earth. He could explain every single piece of the larger puzzle in detail that compares favorably to NASA’s space shuttle preparations (Editor’s Note: Pretty apt comparison – understanding Middle Earth is somewhat like being an astrophysicist).

This detail enables the sort of escapism that we now commonly associate with the genre. Tolkien did, however, have a reasoning behind the immersion. He didn’t desire total escape from the world for the simple reason of forgetting one’s problems. Instead, Tolkien envisioned “escaping” into a fairy tale to be a positive force in the life of a reader. The reader would “escape” into the fairy tale and in so doing would gain a perspective on the real world, whether death, growing up, or temptation. The reader would then enter “recovery”, where they re-enter reality armed with perspective and insight that then helps them deal with the current circumstances they face.

A great example of this is Tolkien’s The Hobbit. The Hobbit tells the tale of Bilbo Baggins as he is caught up in a quest to recover the ancient dwarven realm of Erebor. As an, at first, unwilling participant, Bilbo is brought into a scheme hatched by the grey wizard Gandalf. Thorin Oakenshield, the rightful heir to the throne of Erebor, leads the expedition to save his kingdom from the dragon Smaug along with his dwarven companions and the “burglar” Bilbo. Bilbo encounters all manner of dwarves, elves, goblins, trolls, and men, both helpful and harmful. Highlights include the beautiful elven city of Rivendell, a thunder battle between mountain giants, nearly being eaten by trolls, a shape-shifter that was both man and bear (my personal favorite), a game of riddles with a strange creature, the finding of a magic ring, a huge battle involving all the different races, and of course the rather anti-climactic encounter with the dragon.

Biblo Baggins tells the tale, and he progresses from a homesick and naive hobbit to an integral part of the company and its success. He is aided by his discovery of a magic ring in Gollum’s cave, which we later know as the Ring of Power in The Lord of The Rings. Bilbo grows much in his adventure: he gains courage in the face of adversity, a willingness to lay aside the comforts of home, knowledge of himself and his true abilities, and the openness of heart to embrace adventure and all that it might bring.

This character growth is central to Tolkien’s philosophy. Conflict, and the development of character that arises from it, form the basis of what gives the reader perspective. In other words, as Bilbo faces the adventure, how do we face our issues and problems? Bilbo’s answers to the various struggles of the adventure (as well as simply the adventure itself) serve as moments of introspection to put ourselves in that plight and imagine our reaction. Out of that empathizing comes the core truth that carries over into the real world. This is the step by step process of what Tolkien refers to as “Escape and Recovery”. The story serves less as an escape from our problems and more as a safe place to gain helpful perspective on ourselves. We come out of the experience better prepared to face life than when we entered the story.

This personal betterment was central to Tolkien. “Fairy Stories” were never “just stories”. They existed to help us become better people. Their fantastic and alien worlds opened our eyes to new ways of seeing our own world. These characters helped us see ourselves and the people around us in different lights. Their conflicts and solutions left us with valuable insight on the troubles of our own world.

60 years later and Tolkien’s work remains as popular as ever. Not only that, but since his lifetime the fantasy genre (or “fairy story”) has taken its place on the bookshelf of every store and millions of readers. While the stories themselves became as varied as the authors that wrote them, Tolkien’s philosophies live on in their works. Tolkien’s work took the genre to heights it had never before thought possible.