In light of recent events, this felt especially relevant.

At the advent of Hotline Miami’s release, an explosion of critical acclaim happened instantaneously. Not only was the game seen as fun and challenging, but it was also perceived to be a subtle commentary on video game violence. Wow, everyone had an epiphany all of a sudden. There’s violence in video games? Who knew? Who could possibly fathom? If you couldn’t read the gushing, overflowing sarcasm in the last few sentences…well, there it is. Sorry, less savvy readers!

Then we had the school shooting – not so great for people who like violent games like this (which, as I would imagine, includes mostly everyone playing video games). Sandy Hook’s horrific events inspired quite a controversy regarding such games as this. Should we enjoy it? Was it really a commentary on video game violence? Or was it simply meant as a challenging game with a unique aesthetic (I have my own problems with the game, granted, but I’m echoing the general sentiment of the discussion here). Or, is the soul of video gaming sick when we enjoy shooting people in the face? As aptly put by the Rooster:

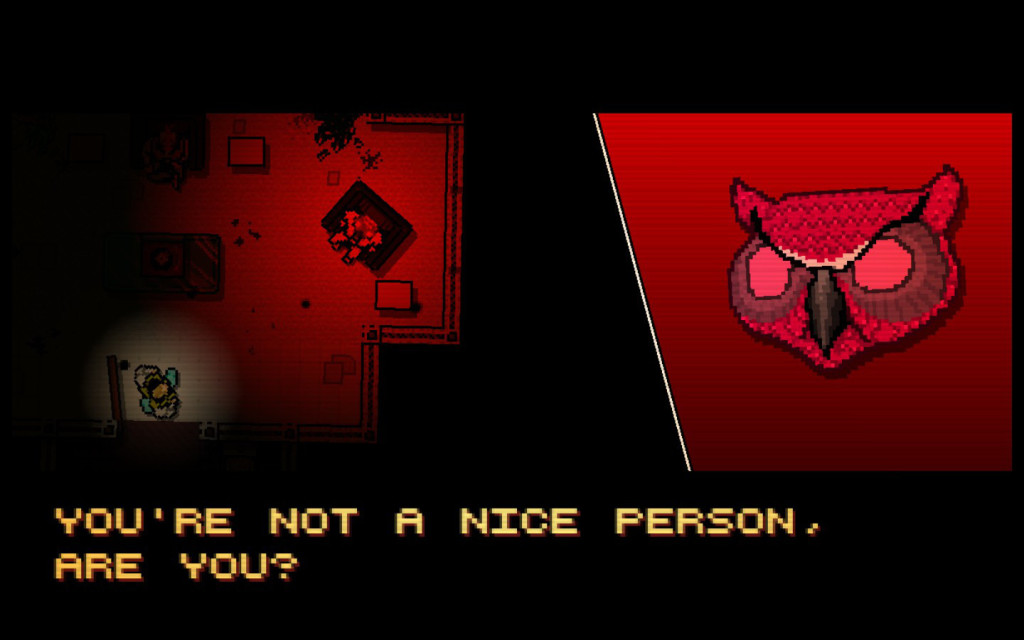

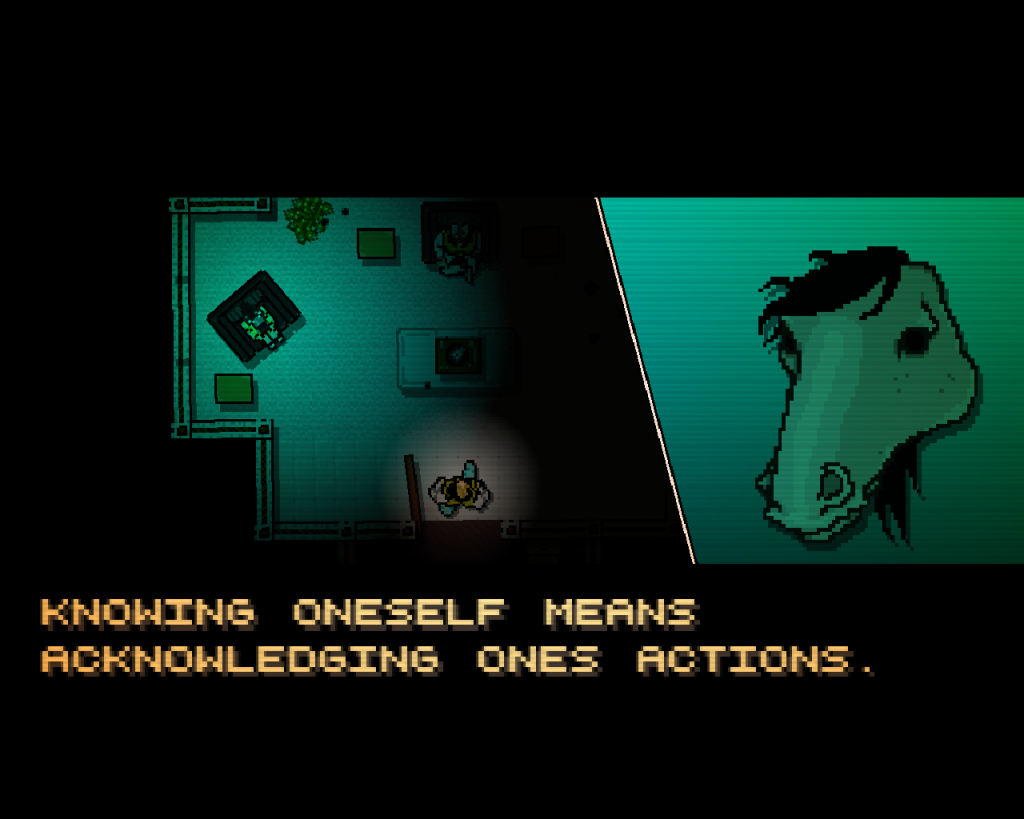

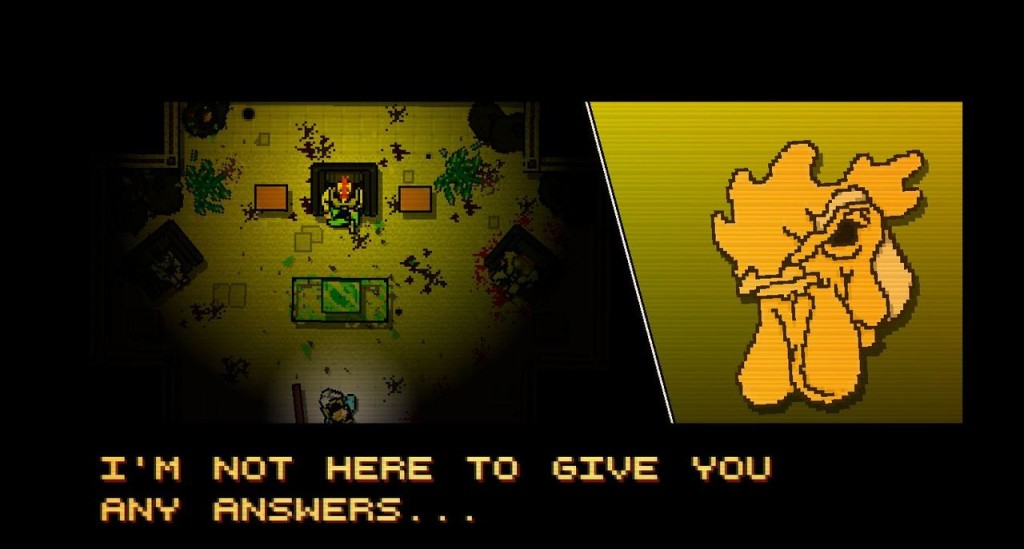

Throughout the game, mysterious phonecalls and messages come from unknown people and guys in animal masks. They ask you cryptic questions such as the one above, and you continue to fulfill the requests from the phonecalls: to murder everyone at a particular location. Clearly, either you aren’t in your right mind, or this game’s supposed to be a stylish yet shallow game, much like the ultra-violent 80s inspired film Drive. I’m guessing a little of both. The casual observer takes a look at the game and sees a problem. Then, they are incredibly amazed when they find out they murdered a bunch of guys at the whims of mysterious messengers (or game designers, take your pick). Bioshock did this before, I suppose, but Hotline Miami makes the killing a central point of contention. Is this really what’s happening in the game? Who knows; the developers aren’t talking, but the gaming public has projected a particular image upon it, and now we run with it.

It’s interesting to note all the people feeling bad about hurting people and/or things in Hotline Miami. Was this a magical realization? Did they not realize that violence happens in nearly every game ever made, whether of the realistic or cartoonish sort? Perhaps playing them from near-birth has made the “immersion” aspect irrelevant to me. I find myself without any qualms of playing most games, regardless of their content. It’s a conscious decision on my part; what I see when I research a game isn’t the aesthetic elements. Rather, the mechanics remain the most important to me. Are they fun? Will I enjoy this? Does the developer know what they’re doing with this confluence of systems, or have they totally made a mess of their own game?

Someone has certainly said this before, but what if stomping on a Goomba wasn’t simply an act of a jumping stomp and a “whup” sound? What if the Goomba, a living mushroom creature, exploded in a shower of blood and guts. Would you feel bad then? Should the aesthetics count for the moral qualities of a game? Is this one too many rhetorical questions strung together in a row? In that sense, I don’t see much of anything in Hotline Miami. I see violence, sure, and the soundtrack’s a bit unsettling, but it’s nothing I haven’t seen before. Plenty of games have made the player into a murderer or make him/her complicit in the action, but I’m guessing the context really riles people up. The concentration required to weave a web of cautious, precise, and horrible looking violence means they become more immersed in the experience then they expect. They find themselves questioning their role, and why it is that they seem to be murdering people.

Of course, strip the aesthetics away and you’re left with a pretty familiar experience that, in any case, could fit onto an Atari 2600 cartridge. It just happens to have a theme – a theme that provokes uneasy feelings, at the very least, and outright disgust at the very worst. But that’s the same with nearly every military first-person shooter released in recent times, so it would seem that immersion comes from a variety of places. We could say that it does depend on the player. I don’t have any immersion in these experiences because I know, at heart, that it’s simply a video game. I analyze the mechanics and search for what I’d call “efficiency” – what is the most efficient solution to the problem that game presents? In that manner, shooting dudes in the head becomes a puzzle indistinguishable from a (bloody) Rubik’s cube.

I can probably thank my childhood for this. I was playing Mortal Kombat when I was five years old. The game was, to be blunt, rather funny, satirical, and over-the-top in its use of violence. To me, it wasn’t “cool” in the sense of aesthetics, but more in how I could defeat my father and uncle at the game. It got to the point where, when I used Stryker’s Baton Toss move, they would throw the controller in frustration at a wall. They had no counter and no ability to react correctly; I had found the most efficient strategy, and it worked flawlessly. My brother was doing the same thing ripping people to shred with Kabal’s giant ground saws and projectiles. Projectiles were, apparently, “unfair” and we had to stop playing the game. Nobody wants to see their uncle pop a jugular vein and die when they’re playing a video game, right?

My memories of games come from what I learned, not whether Sub-Zero can rip your spine out; fatalities revealed my success/failure at winning, and showing off. I learned early in life that the game, whether it looked cool or not, still based its good qualities on the mechanics making it work. My parents taught me that there was a clear difference between appearance and reality – what happened in a game and what happened in real life were utterly distinct concepts. This disconnect probably fuels my current tastes in some odd games. Japanese games understood this and exemplified this by definition; Western game developers, of the console and arcade variety, aped their predecessors and contemporaries. Eventually, the American companies realized that they couldn’t compete on this fundamental “mechanics” level. They needed something they were excellent at producing, something that made a lot of money. What better way to succeed then through shock value, realism, turning games into movies – into experiences? We made games that were TOO immersive, a subtle influence on the children of today. The transformation’s already occurred, and now we are here standing with blood in our hands.

Or are we? What a gross generalization that would be! Every person comes into these games/experiences with a different intent. Me? I see a game. Others? They see a realistic (but not really) and engaging experience about killing people. Perhaps they identify with the protagonist in some way, and feel some sense of power or fulfillment – control over their lives they don’t usually have. Perhaps some believe they’re so entrenched in social media that they can’t objectively see why games motivate the kind of behavior that Adam Lanza exhibited. Thus, we need a virtual ceasefire, or at least ban something (Yes, Jack Thompson still lurks on the fringes of the Internet, waiting to pounce at a moment’s notice). But then you find out that Lanza’s mother owned a gun, took him to the shooting range, and let him indulge in these ideas in the real world, and a different story emerges. Video games look like an innocent bystander in a sea of bad decisions. Lanza had high-functioning Asperger’s, and his mother was in the process of institutionalizing him forever – do we really think our children remain stupid? Perhaps his father left him. Who knows? All of this stuff remains pure speculation. No one can know the mind except God.

Yet, I’m not here to offer you comfort, denizens of the gaming culture. No one’s going to stop playing video games due to some major outlet moralizing about the affects of video games on our youth. It’s not as if anyone’s going to really change their ideas or views regarding the issue. Those that like video games will enjoy them; those that don’t, will continue to not like them. Same goes for everything in this life. The media will harp on the issue for about a month, and then nothing will happen. Politicians claim to support gun control to gain support from them constituencies,(or politicize a tragedy) whether or not that’s actually case. Not as if any of us will care after the story leaves the public consciousness – and that could be a long while, as this is, simply put, a GOLDMINE for news outlets.

We, though, stay as much to blame. People will send “their thoughts” towards these people in their tragedy for a little while and then move on. We’ all engage in temporary abstinence/blame games and then everyone moves on with their lives. Time and time again, that’s exactly what has happened with every other entertainment media and the culture of violence surrounding it: temporary recognition, lapse into apathy, and then who really cares until the next situation shows up? We’re a reactive culture, one that always addresses the current situation rather than the root. The current generation now coming to adulthood became total narcissists, the same environment where no one does anything wrong and no one does anything bad – something else has already caused it. It couldn’t be me!

The mind has plenty of self-defense mechanisms; it constantly works against self-improvement, perpetually justifying a lack of action through the “sending” of feelings, and otherwise. Regarding Christianity, “prayer” becomes a self-defense mechanism so that I can “help” from afar. There’s no work in doing that. Prayer’s easy; changing yourself and what you do is HARD. It is in this sense that Jesus speaks in Matthew 5:

21 “You have heard that the ancients were told, ‘You shall not commit murder’ and ‘Whoever commits murder shall be liable to the court.’ 22 But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother shall be guilty before the court; and whoever says to his brother, ‘You good-for-nothing,’ shall be guilty before the supreme court; and whoever says, ‘You fool,’ shall be guilty enough to go into the fiery hell. 23 Therefore if you are presenting your offering at the altar, and there remember that your brother has something against you, 24 leave your offering there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother, and then come and present your offering. 25 Make friends quickly with your opponent at law while you are with him on the way, so that your opponent may not hand you over to the judge, and the judge to the officer, and you be thrown into prison. 26 Truly I say to you, you will not come out of there until you have paid up the last cent.

27 “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery’; 28 but I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust for her has already committed adultery with her in his heart. 29 If your right eye makes you stumble, tear it out and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. 30 If your right hand makes you stumble, cut it off and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to go into hell.

Intent counts for everything. It is what makes an action right or wrong, a situation just or unjust. When that intent becomes perverted and twisted, it leads to environs full of vacillations and indecisiveness. These feelings, further, find justification in our own psychological mind-games. Perhaps that’s in the same way that the initial emotional reaction will tend towards apathy or disinterest as soon as the media wrings every propaganda drop of news and ratings out of a horrible event. Our culture’s one of sympathy rather than action. Caring’s easier than doing. And stopping the violent video game remains much easier than confronting sinful humanity.

It’s much easier to blame something – anything – other than those responsible. Video games become a scapegoat, a mere pittance in the wake of a sinful nature unable to confront itself within the individual or within society. And that’s just the way the Enemy wants it: self-absortion, moralizing prescriptions, hysteria. People turn against people – arbitrary dichotomies form, an uncivil discussion emerges. Even in the worst of times, it isn’t about those poor kids who got shot, or about Adam Lanza, or his mother – rather, it’s about ME.

“The worst of us cannot be the best of us,” we say, and we find every excuse to the contrary. He cannot be like us, this monster; he has a mental illness, or he had a bad background, or he played violent video games. They feed into each other and work into our pride, even as we forever declare ourselves as “humble”. We project ourselves onto the world and blame it, rather than us. It’s how gamers explain away violent video game feelings and how the general public blames those same games – each has a particular feeling towards the situation, and only projecting it outside will get it out! We hold these feelings and find causes for them in the outside world.

We’re not humble; not really. We’re not good people by pointing out the problem, or even pointing out the problem in ourselves. Just recognizing a truth about ourselves doesn’t fix the problem; it’s just another defense mechanism. Everyone’s self-interested at a basic level whether you admit that or not, and our psychology works into this better than even we realize. If you take original sin seriously, can you really doubt this notion? And what matters, then, is ME. How I FEEL. And not what I think, or what I do, or God above who loves us all. Something else can always be blamed (so can God, for that matter). Here, we find the crux of the issue: an individual did it. They may have been influenced from a variety of factors, surely, but it all coalesces into individual responsibility. As it says in 2 Corinthians 5:

9 Therefore we also have as our ambition, whether at home or absent, to be pleasing to Him. 10 For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may be recompensed for his deeds in the body, according to what he has done, whether good or bad.

Without parents teaching their children the right things, without our culture letting people learn from their mistakes, and without an understanding of the difference between appearance and reality, these events will continue again and again. The issue isn’t the violence in games, but the violence we do to ourselves day after day, fighting against any form of improvement, accepting sin in our lives. We live the self-aware ironic lifestyle, too busy analyzing things to do things; a culture of consumption rather than action. Christianity gives us the tools to fight that corruption; Christ gives us freedom from sin, and narcissism, and subjectivity’s stranglehold on everything.

If Hotline Miami’s about anything, then, it’s this: stop following orders. Stop doing what you’re told. Stop doing what you think is “rebellious” or “hip”. Stop analyzing everything. Put yourself in the mindset to become more Christlike and less a caricature of a person who sympathizes and distances his/her self from human life. From real people who need real help. Stop being the person that blames everything but YOU. If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the status quo. I should know; I’ve been there, and so have you. If you want to change something, you’re going to have to do that yourself. God will help, but initiative is key. Otherwise, you’ll descend into the same lack of self-awareness that makes the game so devastating for so many when they let go of the weapon and realize what they’ve done: they killed themselves inside.

11 Therefore, knowing the fear of the Lord, we persuade men, but we are made manifest to God; and I hope that we are made manifest also in your consciences. 12 We are not again commending ourselves to you but are giving you an occasion to be proud of us, so that you will have an answer for those who take pride in appearance and not in heart.

A culture focused on what “appears” as the problem, the appearance rather than the heart of man, cannot long survive. Without action, what can we be?

22 But prove yourselves doers of the word, and not merely hearers who delude themselves. 23 For if anyone is a hearer of the word and not a doer, he is like a man who looks at his natural face in a mirror; 24 for once he has looked at himself and gone away, he has immediately forgotten what kind of person he was. 25 But one who looks intently at the perfect law, the law of liberty, and abides by it, not having become a forgetful hearer but an effectual doer, this man will be blessed in what he does.

James 1:22-25