Last updated on March 4, 2013

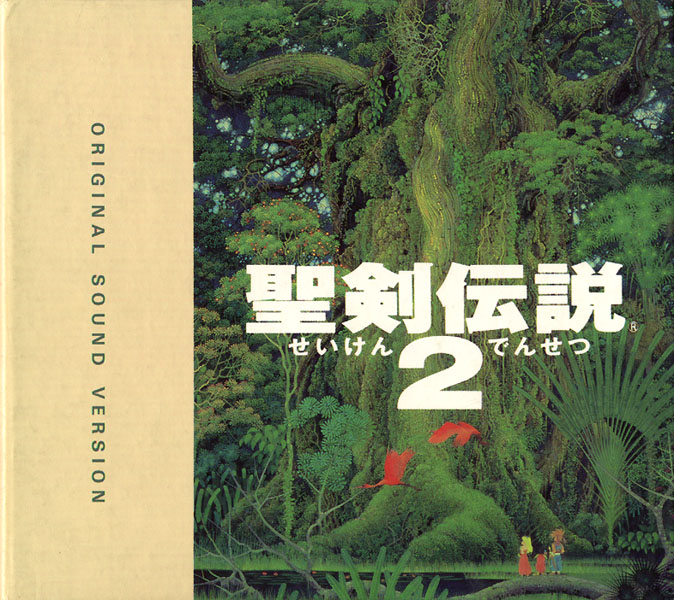

Hiroki Kikuta is the man.

Now, I’m sure you noticed that no where in my entire article series did I pay much attention to the music. Well, in addition to pimping out another article out of the series, I also think it’s worth discussing in and of itself, rather than along with all those other elements.

Games have music, true. Some games have better music than others. What allows us to evaluate why that music is good, though? It has as much to do with the experience associated with the music as it does the music in itself. Let’s say that a great deal of video games tracks, in that sense, are derivative and not at all engaging. Rather, what makes video game music unique is the emotional connection forged by playing the game, taking in the aesthetic beauty (or lack thereof), and hearing the music at the same time. It’s the same reasoning why, for me, ambient soundtracks always feel like a wasted opportunity to engage the player into the experience. Whereas I can see this working for some games by adding a certain atmosphere (stealth games, for example, could benefit by silence and moments of punctuated sound), it doesn’t work for all games. Even Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory’s soundtrack, by electronic artist Amon Tobin, is quite awesome for the genre of game it was attached to, and made that experience much more memorable than it otherwise would become without the audio augmentation.

Secret of Mana, then, has a brilliant soundtrack for I can associate most songs with a particular feeling or moment in the game. From the opening’s wolf howling and the pitch black of “Heart of Darkness”, to the adventuresome nature of “In the Thick of It”, to the utterly creepy gamelan of the Ruins in “Ceremony”, each track really nails down something that’s difficult to describe in words. Thanatos, for example, wouldn’t be nearly as scary without that setting in the game, as he’s the “cackle and tell the protagonists all my plans” kind of villain; that the fast-paced remix still gives you the same idea really shows the quality of the musical themes to sustain the game’s moments. When I feel like visiting the dwarves, I’ve got “Distant Thunder” on my mind. If I’m entering a Mana Temple, “Mystic Invasion” pops up in the mind, and when I’m wandering around the forest of the four seasons trying to figure out where I’m supposed to go for five hours, “What the Forest Taught Me” drills itself into my brain. This stuff still affects me now as much as it does then, including the fright I first felt from the Ruins. Video games affect you more than you can imagine because they’re interactive, and even the music lends itself to that interaction.

Kikuta really crafted a masterwork here, and everything just fits. I find it difficult to explain why (hence, why I’m writing for a blog), but every piece of music fits exactly where it should, and it still works today. Even “Leave Time For Love” works in its context, which has the most innocuous title ever for a final boss dungeon, yet sounds like something you’d hear at a dance club. Who knows why! Not alot of game music today can claim such a high mantle, although many certainly try to add as many choirs and orchestral queues as possible. It’s not just memorable; it’s catchy, even when it sounds mournful in “Still of the Night”. Japanese composers just tend to nail that “video game” sound that’s so distinctive.

You might say, in the same vein, that music was essential to the Church for the very same reasons. That’s why worship music for two millenia has always been successful in conveying emotion and reaching an audience – because they have all had that experience of Jesus Christ, and to lift up their praise to God is augmented by the music as a mental association. Heck, it’s why a lot of hymns contain literal portions of Scripture strewn about their melodies, and why they tend to be simplistic, multi-versed, and catchy. There’s a 150 Psalms that made their way into the Bible, for goodness sake, and it’s not all that much of a mystery why: praise to God can involve song and music as captiviating elements. Even Acts 16, when Paul in Silas are in jail, show that praise and rejoicing can be found in any situation: “25 But about midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns of praise to God, and the prisoners were listening to them…” It’s integral because even the tune, not just the lyrics, bring about the feelings of redemption, love, and grace that characterize the grateful life of a true Christian.

I’ve always found a bizarre relevance to video game music to church music in that sense: they have a very similar set of goals, and when they succeed, those songs tend to be beyond any kind of criticism whatsoever. How many Christians in Western societies don’t know Amazing Grace? And what gamer doesn’t know the Final Fantasy main theme? They are indelible parts of the experience. For this case, it’s what makes SoM such an unbelievable game that hasn’t been duplicated. That these moods can be created using the SNES sound chips baffles me to no end; that synthesized music still retains that human element and emotion makes even less sense. I can’t name the tune by name, but I can sure recognize SoM’s distinctive sound. World of WarCraft doesn’t have music that is quite as good as this, for sure!

The only downside to this collection is that most of the songs, while unbelievably awesome, only loop once. Video game music tends to be short, and then looped repeatedly in game without pause. To convert it to a soundtrack format, then, means the songs have a definite stop and end point. For a one disc album, you get one loop, and this means the songs are very short. While I’d say you should buy this, I’d also recommend downloaded the SNES sound files, then looping it twice yourself for a more robust experience. Who uses CDs anyway, other than for collecting purposes (I do, but I’m just saying). As for now, it seems like it’s out of print, but I imagine a good copy could be found for thirty dollars or so.

Also, play the game first. It’s on Nintendo’s VC or even Apple’s App Store. You’ll thank me later.