Okay, that’s not quite right. Technically, we need to move back a layer. Alan Wake’s creator, Finnish writer Sam Lake, writes in a style that fits Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth” quite nicely.

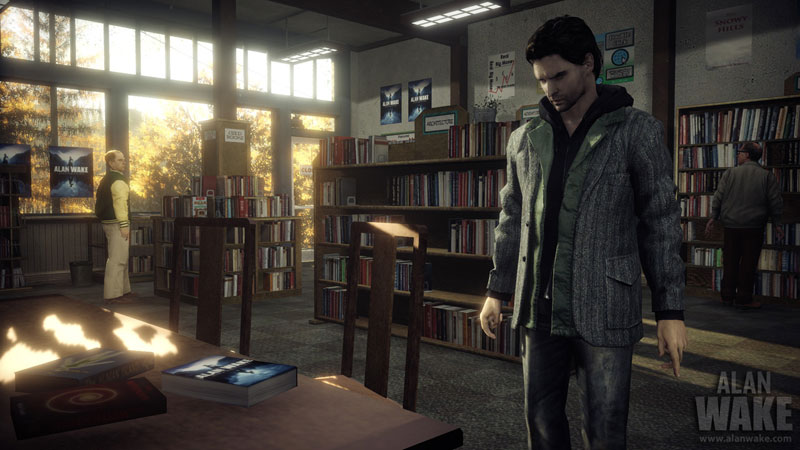

I played Alan Wake and its side-story sequel Alan Wake’s American Nightmare, and let me say, I was impressed. That’s an understatement. I really, absolutely loved playing these games, and I can’t wait for whatever is coming next for Wake.

A quick introduction for the uninitiated:

“My name is Alan Wake, and I’m a writer.”

Specifically, Wake is a writer of best-selling horror, a fictional Stephen King. As the game opens, we learn that after Wake’s last book (his best to date according to both critics and sales figures), he’s experienced insane writers’ block. How does he top this?

Thus, his wife schedules a vacation for the two of them in the Pacific Northwest. She also gets in touch with a doctor and therapist who claims to help with creative types and their various “blocks.” After a relatively peaceful day, Wake and his lady stay at this house built on a lake in the middle of a dormant volcano. Wake’s wife thinks it will help inspire him. The third-party observer (reader/gamer) can immediately recognize the setup here. Something is wrong. Really wrong.

Night falls, nightmares take place, Wake sees his wife fall into the lake. When he comes to, he discovers that everyone believes he is the only one in town: his wife was never there. Now, the horror story revolves around Wake himself.

The gameplay involves shining flashlights, shooting guns, and reading pages out of a book that Wake somehow, impossibly, wrote immediately after his wife fell in the lake. And it’s all glorious.

(Think “Secret Window,” except this time, our hero isn’t deranged: he’s right to distrust anyone who says he’s crazy, especially that nutty therapist!)

As more is learned, and especially as the sequel pushes us forward, we find that Wake’s “enemy” is darkness itself. The powers of darkness. The personification of darkness. The darkness within himself, and the darkness of humankind throughout history. How does one combat this? Even by the end of the second game, the answers are only beginning to trickle in.

But with the help of another writer, Wake finds a way to “wake up” from the darkness and move forward in this seemingly eternal struggle. The story-telling remains fantastic throughout, even when it’s absurd (the “rock concert” in chapter 4 of the first game is somehow both cheesy and sublime).

In playing through all this, it didn’t take long for me to realize that Wake’s creator was either a fan of Campbell’s “monomyth” theory or unintentionally proved Campbell’s point about how the best stories are told.

There’s a lot of narration in these games about the struggles between light and darkness, and the progress and transformation of a singular hero who must overcome. In Campbell’s best-known work promoting the concept of the monomyth, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, he writes:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

Famous religious examples fit this model: Buddha, Moses, and (obviously) Jesus. And then there are epic tales like Gilgamesh that fit this model as well.

And, of course, film, television and games fit the model all the time. Jenova Chen cites it as a major influence in the game Journey.

But for me, it was especially apparent in the story of Alan Wake. Here’s a guy who finds himself stuck in a world that is “stranger than fiction,” and his primary weapon is light (flashlights, street lamps, the sun, anything will do the trick).

Christians tend to be conflicted about Campbell’s theory, primarily because it clumps in Jesus with a bunch of other people. It’s like that Zeitgeist movie that’s popular on YouTube. Jesus wasn’t the first and there’s nothing unique about his story and journey, so how could he be God incarnate?

I get the complaint, and I get Campbell’s side of it as well. How I resolve it, as a Christian, is something akin to what Tolkien said to Lewis about myths in general. Instead of flattening these myths and giving them all equal importance, I see it that the archetype is based on the truth of the Gospel narrative. For those myths that cropped up (real or not) before Jesus’ time, they were foreshadowing the truth of the universe. For those afterwards, they are reflections.

But, most importantly, many of these eternal light/darkness struggles involve some kind of triumph of the will, or reaching some level of purity or enlightenment. According to Christian tradition, Jesus Christ already “had it.” He was already fully God and fully man. The transformation was complete. There was an element of struggle (Gethsemane), but the central theme of GRACE is (as far as I can tell) outside the realm of Campbell’s monomyth. Where does grace enter the picture humanity through Buddha, Gilgamesh, or Alan Wake? There’s often a miracle and perhaps a happy ending, but what lasting impact does it have?

I’ll end my ramblings with this: I love Alan Wake; it’s a great story and a great adventure, but it doesn’t change me like The Greatest Story Ever Told does. It is a reflection in a dark mirror, put together by a Finnish guy and a team of programmers and artists (Editor’s Note: Remedy Games, who also made the excellent Max Payne 2). I want to see more of this, but I don’t think this story (like most “monomyth” tales) has room to truly reflect the Gospel, which to me, rises above the monomyth as the only “true myth.”