Last updated on January 19, 2014

The imagination is an interesting thing. How do you define it? What of the pictures we draw before our mind? How does it work within a Christian concept? It relates to the ideas of consciousness and reality, and theologians (as well as philosophers) continually deal with this issues. Although not much of a concern in our modern theological conceptions, there is much to be said for the creativity and imaginative impulse of the Christian mind – well-developed ones, at least.

So it is that many people tried to define this impulse using the rational and logical developments within their minds. The first one that comes to my mind, of course, is Descartes. If one wants to start anywhere in this respect, you must deal with Descartes. The conception of the imagination in Descartes’ thought is an essential part of his proof for God and the immortal soul. In fact, his very methodology requires a rather active imagination. Let me explain.

For those not in the know, Descartes remains forever famous for the cogito ergo sum in philosophy – I think, therefore I am. In a bit of hypothetical skepticism, Rene Descartes posited that if he were to doubt all thing that could be reasonably doubted as true or real, such as sense experience or thought, he would find the real. He knew God was, in fact, real, but he could not prove the existence of himself in order to actually confirm that. An evil God could also cause this, as far as he knew, for he could not tell the difference between the real and unreal. Where does one begin such an operation?

In our example here, imagine you, yourself, as a person. You think you are real, that you exist…or do you? It’s difficult to prove such a thing when you approach it logically. Even in the 17th century, people were pretty certain that the human senses were flawed and unable to perceive everything accurately. In that case, how exactly could we stand on solid ground to prove our own existence?

Descartes peeled back the layers, doubting all that existed, until he stripped away all else. What exactly remained? Well, what still continued was doubt, and more specifically thought. Descartes found that he, himself, was a thinking thing and continued to exist as a thinking thing even if nothing else around us existed (the concept is usually now called solipsism). So it was that the cogito ergo sum emerged as a starting point, a foundation for further philosophical knowledge after affirming one’s own existence. After all, if it is turtles all the way down, where do you start?

For our subject here, we want to investigate Descartes’ view on imagination. His scholastic (as in the theological/philosophical educational method of the early 2nd millenium AD) upbringing brought along a host of ideas derived from the works of philosophers like Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas; the same language they used was simply adapted for Descartes’ work in the 17th century. Descartes uses scholastic terminology in his method of philosophical doubt.

However, in his process of doubting everything, Descartes changed the definition of imagination slightly to fit his own views. Not only was it considered a separate operation from the essential functions of the mind, but its primary use consisted of image making and nothing more. Descartes made certain to separate it from the understanding, or intellection, as the imagination must rely upon the senses which are inherently unreliable. Thus, as a natural conclusion, the imagination cannot be necessary to the existence of a thinking thing.

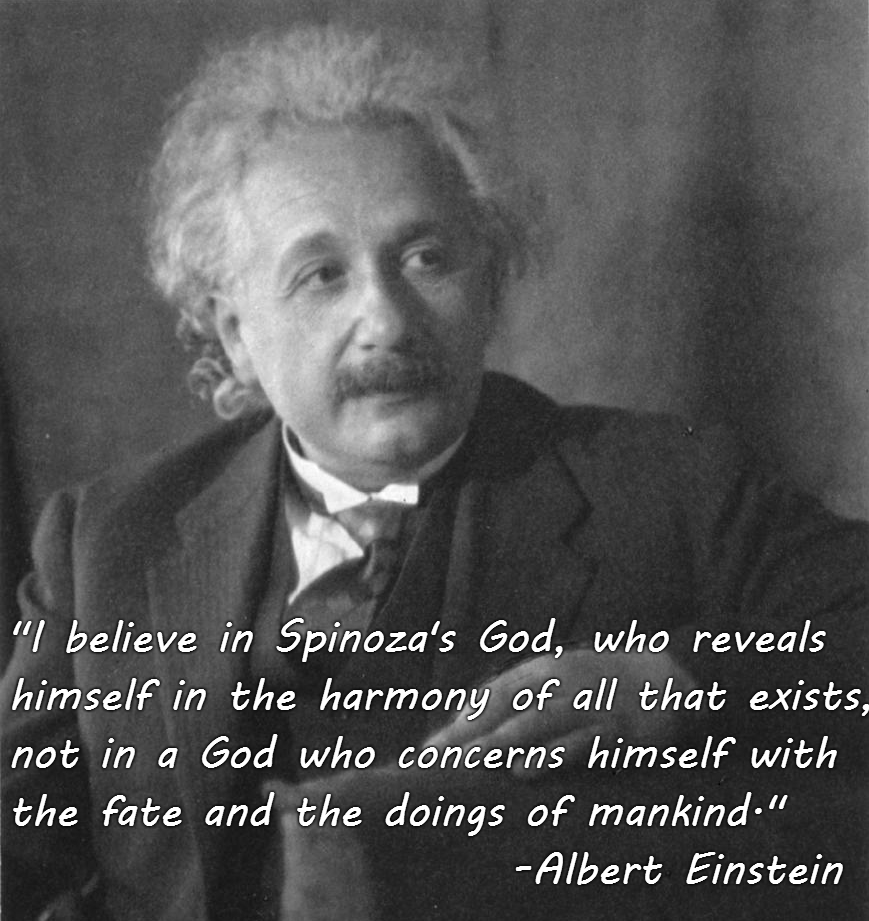

In my view, Descartes is incorrect in this regard; the imagination cannot be separated from the idea of a thinking thing. The imagination cannot exist solely as an image-making device; what of the personality, or creativity, or even the mode of discovery which Descartes employs? All of these, to a degree, require the imagination. Descartes can only understand what a thinking thing might be because he can imagine it. Thus, unless he wishes to take the ultra-rationalist route of Spinoza, as well as removing the idea of a “person” from the discourse, Descartes must leave a greater space for a broader definition of imagination. Otherwise, he must relinquish his Christianity or his ideas as a whole.

Why do I say this? To leave no room for doubt to this conclusion, one must define imagination exactly as philosophy has defined it before Descartes. In the 17th century, academia was still ruled by the iron-hand of scholasticism, founded by Aristotle (albeit not intentional) and continued for a Christian audience, like Descartes, by Thomas Aquinas. Aristotle makes it clear that the

…imagination is different from both perception and thought, and this does not occur without perception, nor supposal without it.

For Aristotle, the imagination

…is that in virtue of which we say that an image occurs to us and not as we speak of it metaphorically…

In light of this definition, the imagination does not exist as the understanding, perception, knowledge, or belief. Certainly, one could only consider imagination as dependent on sense-experience:

…imagination will be a movement taking place as a result of actual sense-perception. And since sight is sense-perception par excellence, and name for imagination (phantasia) is taken from light (pharos), because without light it is not possible to see.

Aristotle always uses common language as a way of grasping the true definition, and in this case there is no exception. Since the Greek word for “imagination” has the word “light” as a root, it is only correct to deduce that imagination depends on sense-experience, specifically sight in this case, which requires light to differentiate objects and perceptions. Aristotle’s definition of imagination became the de facto standard for centuries, and as Descartes was schooled within an Aristotlean metaphysics, it can be no stretch to say this was almost exclusively his definition.

Descartes makes other statements and adjustments to these definitions for use within his process of methodological doubt. Because Descartes must doubt all those things which cannot be clearly and distinctly perceived by his thought, there are certain functions that must be cast out. The imaginatio primarily makes pictures of things. Things can only be perceived by the senses; they are, literally, the fodder for the imagination. The senses, thus, allow for the detection of these things.

However, because the senses are inherently unreliable, the imagination is also based upon a faulty foundation. Descartes states

…I consider that this power of imagining that is in me, insofar as it differs from the power of understanding, is not required for my own essence, that is, the essence of my mind.

In this conception, imagination cannot be part of the pure thought of a thinking thing, simply because without the senses it would not have anything to “think”, so to speak. Descartes uses the triangle to explicate this point. The idea of a triangle does not require the imagination; I can understand what three sides and three angles are without creating an image. The same would follow for a chiliagon, a geometric figure with one thousand angles and sides. Both ideas are understandable – to create images of the actual figures in my mind, however, requires a special faculty like imagination to conjure. Thus, the effort required to create the image is something beyond mere understanding.

On the other hand, Descartes’ conception of the understanding, like Aristotle, does not need the senses or anything else. One can, in his opinion, clearly and distinctly perceive the understanding’s function. The understanding, for Descartes, is more so related to the soul, while the imagination relates primarily to the body. The former is incorporeal, while the latter remains material within this system.

In addition, Descartes believed that the only true substance is mental in nature; the physical substance is simply “material body” rather than “mental substance”. This also allows Descartes to follow Aristotle in stating that only individual substances are true, as each thinking thing, or soul, is an individual person. Thus, one can easily see that the imagination is a secondary faculty of a mind, one entirely dependent on unpredictable forces. For Descartes, its unreliability means it has to be abandoned for proper formulations of reality.

This all sounds well and good, of course. To separate imagination from the basics of thought means that Descartes lets himself wander in hypotheticals and keep philosophical doubt. However, this concept of imagination constrains the idea of thought itself, and it’s quite a wonder that he could claim what he did without imagination.

Part Two here for your convenience.