Last updated on July 6, 2013

Well, this is turning into a bonafide series, isn’t it? In honor of the fact that I have written so much on the subject of the Christian Church’s intellectual (and spiritual) history, I hereby proclaim that I will continue to do it for quite a while. Or until you get bored, either way. Not only does it fit within the theological mold of this website, but it will also give you insight into my particular theology, I imagine, and the very vehement argumentation I make against such things.

Trust me, I have thought long and hard about the subject matter, so I do not take these things that lightly. With that said, let me provide some links for the purpose of catch-up. It’s not essential reading, but I like reading things in order as much as the next person:

- Greek Philosophy and Gnosticism

- Monarchianism, Montanism, and Speaking in Tongues (Part 1)

- Monarchianism, Montanism, and Speaking in Tongues (Part 2

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

To move forward with our current subject matter, we move into one of the most important, and volatile, theological debates to ever hit the Church. Arianism might not sound like anything you heard in recent years, but trust me, its impact has been long felt and the resistance of orthodox Christians to its ideas comes with good reason.

Arianism is named after Arius, a Presbyter from Alexandria in Egypt. He believed that the Father is greater than the Son, who is in turn greater than the Holy Spirit. However, he was a strict monotheist and did not see a “holy hierarchy”. Instead, he believed the Father alone was God, and the Son was the one through whom the Father created the universe. But, and this is the important part, Jesus is only a creature made ex nihilo (which, in Latin, means “out of nothing), not God. He has a beginning – in Arius’ words, “There was once when he was not”.

So imagine, for a moment, what such a belief would mean. If Jesus existed merely as a creature, and not as God, what exactly explains the merit of God’s sacrifice? Does this mean that Jesus presents an example for us as an act of ultimate self-sacrifice? Does this mean that Jesus came down to show God’s love for His creation, except not actually doing anything in the theological sense? Again, Jesus isn’t God in Arian theology, so what affect do the Gospels have on our lives? The divinity of Jesus, that Jesus is fully God and fully human simultaneously, became a widely held belief, but as we see here it wasn’t always so.

For my part, Arius’s theology strikes me as incredibly wrong. How does Jesus, a created thing, save all of mankind if He is merely a man? I would imagine one of the basic precepts of the Bible tells us this much: we are really, really bad at doing things correctly. When God tells us to do anything, we rebel against His will either from lack of forsight or simple rebellion. We need a Savior to help us, for we cannot help ourselves. The Gospel narratives confirm this in many ways; I use Luke 19 as my example here:

He entered Jericho and was passing through. 2 And there was a man called by the name of Zaccheus; he was a chief tax collector and he was rich. 3 Zaccheus was trying to see who Jesus was, and was unable because of the crowd, for he was small in stature. 4 So he ran on ahead and climbed up into a sycamore tree in order to see Him, for He was about to pass through that way. 5 When Jesus came to the place, He looked up and said to him, “Zaccheus, hurry and come down, for today I must stay at your house.” 6 And he hurried and came down and received Him gladly.7 When they saw it, they all began to grumble, saying, “He has gone to be the guest of a man who is a sinner.”8 Zaccheus stopped and said to the Lord, “Behold, Lord, half of my possessions I will give to the poor, and if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I will give back four times as much.” 9 And Jesus said to him, “Today salvation has come to this house, because he, too, is a son of Abraham. 10 For the Son of Man has come to seek and to save that which was lost.”

A few questions: Jesus came to save, but what gave Him the right? So does God grant certain people the ability of salvation, and why? Why doesn’t this come up anywhere in the Scriptural text? I just find Arianism peculiar, but I imagine it wouldn’t be that bizarre to Arius’ contemporaries. As Arius said himself, “We are persecuted because we say that the Son had a beginning…and likewise because we say he is made out of nothing.” Jehovah’s Witnesses use this same teaching today, so there’s a historical line somewhere.

Let’s say that this belief was not rejected out of hand. In fact, he had a great deal of support from other factions of the Church at the time, such as the Origenists of the Eastern Church (who believed much the same, but took a hierarchical position on the Trinity). The Origenists were, in their way, orthodox Christians, but they sided with Arius precisely due to his emphasis on discussing the Trinity. All were monotheists, surely as we are today, but they all placed different emphases on different doctrines. There was not a clear definition or idea of the relation between the persons of the Trinity, and that is what led to these controversies throughout the Church. Considering that most non-Roman territory came to belief in Arianism rather than our current beliefs, things began to escalate.

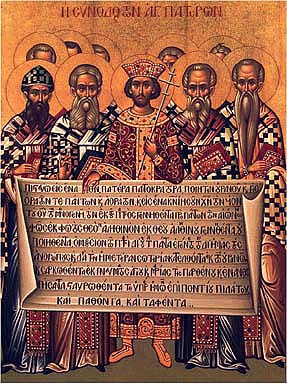

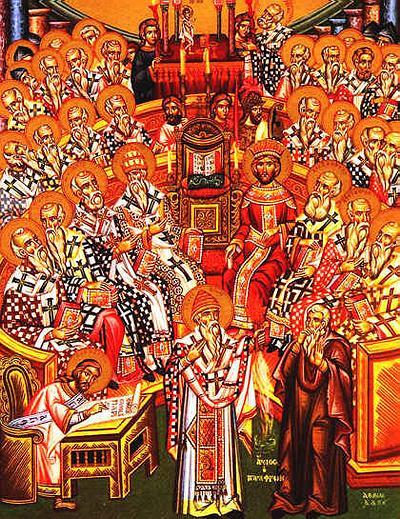

When, in 324, Constantine became the head of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, he was forced to intervene by setting up the Council of Nicea to fix the problem. Not surprisingly, the Creed of Nicea formed here, specifically condemning Arius. You probably know (or could Google) the Nicene Creed, so I’m not going to mention that here. Instead, let’s see the specific lines used that combat and condemn Arius’ beliefs:

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

This might appear like me repeating myself, but look at the specificity of the language. Jesus is “of one being”, with the Father; in Greek, this is homoousios. The problem, in terms of defining Jesus as divine, came from Arius’ use of Scripture to support his own positions. They could simply use the word “begotten” (found in Scripture), but Arius could counter with lines like Job 38:

28 “Has the rain a father?

Or who has begotten the drops of dew?

Of course, this is in reference to God, so we find ourselves back at square one. Using a Greek phrase inside the creed, especially one not found in Scripture, came as a massive controversy, but maintaining the divinity of Christ turned into an all-important idea. If we do not have a divine Christ, we do not have a Savior. On the other hand, Arians and Origenists alike saw a need for distinctions in the Trinity, so they fought back equally as hard. Homoousios did not solve the debate; it merely sparked it further, a surprise attack almost!

In the end, it would appear the Niceans (those who followed the Creed and emphasized Jesus’ divinity) and the Origenists (those who emphasized the three-in-one nature) eventually joined together against a greater threat: The new Arians who believed Jesus was completely unlike the Father. So often does a greater enemy to the faith create a road for reconciliation. Still, let it be known that both sides believed something quite similar. Arius’ belief became a grounding point for both sides to fight one another, even though they believed much the same. This let Arius slip through the cracks for a time. Let’s not make that mistake again with open theology and a weak God.

So much for ecumenical dialogue, huh? Clear definitions and humble talk help a great deal on these issues! Scripture helps out too!