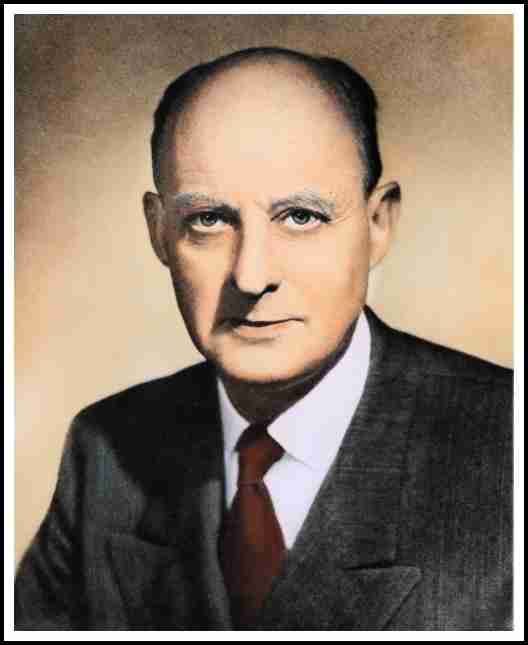

I’d be remiss NOT to mention Niebuhr, even if shortly. But I think I can apply the exact same criticism as contra Bonhoeffer, quite honestly. Reinhold Niebuhr, in some way, exemplified Bonhoeffer’s call for a “secular” Christian. His emphasis on social action and real change, tinged with the Gospel message, made for an interesting mixture. He rejected the liberal charge of human goodness and human progress. Henry Ford’s “philanthropy”, much praised at Niebuhr’s time, was at best mild-mannered Christian moralism, unable to bear the real radical weight of the Christian message.

He, therefore, brought about a return to Augustine’s doctrine of original sin, specifically in reference to whole societies rather than just the individual. This sin extends not just to the individual but to groups in society, each with their own interests. Their self-regard and self-identity creates inevitable tensions in society, a political rather than an ethical relationship, displays and exchange of power rather than of morals. Thus, the realist Niebuhr tries a method that creates a balance between the two groups that allows them both to obtain equal power and to determine the state of a airs – in this does the equal balance avoid the dual dead-ends of Marxism or dictatorship as a solution to social problems.

Niebuhr, rightfully in my eyes, earned the title of “secular theologian” (just look to Barack Obama’s mention of him during the 2008 political season, and you’ll see why), but he strikes a political figure more than anything else to his own detriment. He adopts Christian ideas, but secularizes them as a “public” theologian endeavoring for social change, yet still allowing “secular” persons to join in on the fun. In that sense does Bonhoeffer get what he wants – content without form, but this also misses the point of Christianity as a faith, rather than simply recognition of human flaws. He adopts a Barthian model with a political air, but that still does not solve the problem of authority – why should Christianity be the particular way in which social change comes? If Christianity exists merely as a language for political methodology, why bother with those arbitrary “divine” ideas overlayed on it?

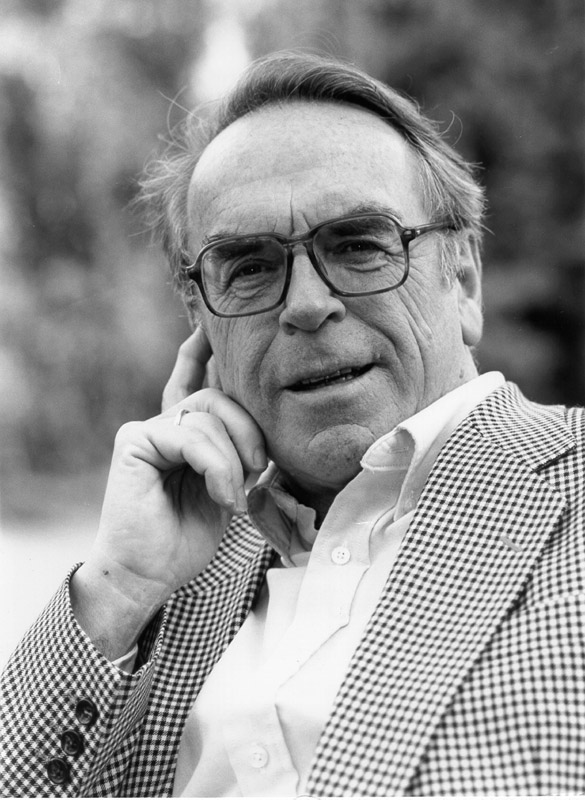

So yes, let’s look at a new idea and critique instead! Jurgen Moltmann tries a different angle similar to the rubric-based approach of Barth while retaining some notions of social justice. Moltmann believed the methodology of theology involves viewing the whole of Christianity from one particular perspective. Moltmann recasts eschatology as a central characteristic of Christianity – not just covering the Last Day as an appendix, but as its center. As Moltmann says,

From first to last, and not merely in the epilogue, Christianity is eschatology, is hope, forward looking and forward moving, and therefore also revolutionizing and transforming the present. The eschatological is not one element of Christianity, but it is the medium of Christian faith as such, the key in which everything in it is set, the glow that suffuses everything here in the dawn of an unexpected day…

Given these platitudes, Moltmann casts eschatology as a revelation as a promise and ground for future hope, even if that hope is provisional, fragmentary, and difficult to see in advance. All Christian action must be viewed in the light of future promises, for the future is already present in the promise of Christ. Work for change now on the basis of future hope as a part of the community, or as Paul says in I Corinthians 15:58,

Therefore, my beloved brethren, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that your toil is not in vain in the Lord.

However, his Christian theology, as with many of the Neo-Orthodox thinkers, is not a traditional theology. We know God, for Moltmann, primarily as a suffering God of love. God can change if God wishes. God freely allows God’s self to sufferr; no external force makes that decision for God. God voluntarily suffers out of love, not of coercion. God opened God’s self to the possibility of being affected by creation in an act of love. God, then, suffers with those who suffers; that remains the only proper Christian response to evil, as no speculative theodicy could sufficiently (or has sufficiently) answered that question.

Even in Moltmann’s later works, he continues to take one aspect – whether suffering, or eschatology, or something – and makes it into the primary interpretant, which somehow explain everything else. This approach seems insufficient to the complexity of Scripture, a human attempt at simpli cation. Why are all his concepts from the New Testament Christ, for example, and not from the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament God? Why do they not deserve equal authority as common sacred texts to the whole of Christian faith? It interprets the concepts derived from one to create the theology of another. Something must always be de-emphasized for one thing to become the primary concept of Christianity in this approach.

In fact, we could call this the easy sweeping criticism of most every person who gained the Neo-Orthodox moniker in academic circles. In their criticism, they eventually make their central concern as the focus of Christianity, to the deference of so many other elements. While this might work as a reactionary measure (as in the case of Soren Kierkegaard), it simply fails in the vast history of Christianity to make a dent. Their focus, so individualized as to become meaningless unless in the context of the author’s personal life, really show us the long and the short of the whole venture.

Whether God becomes a vehicle for political ideas, an associate sufferer, the Word of God, a God that does not intervene, or even something wholly other, you know one thing for sure: something’s bound to disappear in the process of recasting God in the image of something else. I suppose the Christian Church needs a variety of perspectives, but none of them should claim primacy by virtue of a twisted Biblical/spiritual contortion. That’s just my opinion on the matter, but I think that would work as a good rule of thumb for theology in general.