Last updated on September 6, 2013

Unfortunately, much as I like Zwingli and much as most Protestant Christian denominations of the conservative type plagiarized many of his ideas wholesale, he finds little mention in Christian circles today. Perhaps because he died as a battlefield medic too early to craft a treatise, or maybe we just like people who write big books. Rather, we mostly associate the Reformation with both Martin Luther and John Calvin. Let us go to them in term.

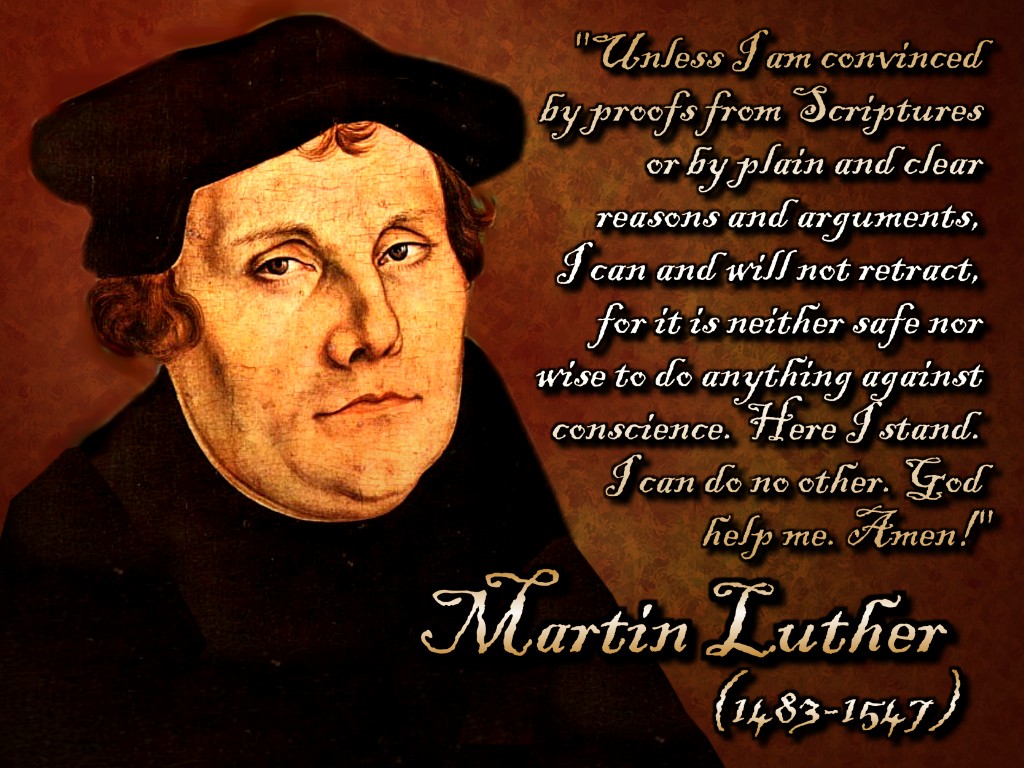

Martin Luther was, as the story goes, a normal German guy. Other than the upper middle class (for his time) upbringing and stand-out academic credential which afforded him a place in law school, no one would fine Luther’s story very remarkable. But, then again, God uses the most unlikely (and probably people lacking self awareness) people to bring about great change, no? Luther, however, never finished his law training, instead opting to become an Augustinian monk; he disappointed his parents, but then again most saints do!

We might call this sudden change, as all the history books commonly agree, born out of a particular worldview. From a young age, he was mired in the eschatology, demonology, and need for religious expression that characterized the early 1500s. Gabriel Biel’s theology found itself exacerbated by beliefs in the end of days and a theology crafted towards a fear of hell. It was understood that the second coming of the Savior, Jesus Christ, was imminent (does this sound familiar? Does it?). Because of this perception, the appearance of demons, witches, and evil spirits occurred because they had little time left to torture the servants of God. The need for sacraments and ceremonies increased, not only to protect one from evil spirits, but to ensure one’s salvation. Religion, in the sense of orthopraxis (right practice), was instrumental in the lives of the people of his era.

Luther found the overbearing judgment of God an unlivable state; he had to serve God to ensure his own salvation. Thus, Luther found God to be a stern avenger and judge, as well as a protector. The former, however, had greater prominence. Only the assurance of the compassionate Virgin Mary, along with the saints, relieved his all-consuming fear of divine judgment. Luther was heavily influenced (as I will continue to emphasize) by the work of Gabriel Biel, who believed that a non-Christian first has to earn grace by doing one’s best, as we discussed already. It is only after this that God bestows a person grace to do good work.

Luther could not understand how a supposedly loving God could possibly require a human being to earn their salvation in this way. At one point does one earn such grace? God, in Luther’s eyes, required such a standard as to be unattainable by a human being. The divide between God and man was too great for him to handle. There was no assurance of divine acceptance in this system, and these tormenting fears led Luther to become a monk at the age of twenty-one, not only to find the truth but to avoid God’s judgement in any way he could! Even becoming a monk did not allay Luther’s fears, as he continued to wrestle with the text that bore down upon him and the weight of his sinfulness.Luther himself says

Though I lived life as a monk without reproach, I felt that I was a sinner before God with an extremely disturbed conscience.

This was especially prevalent in Romans 1:17, which Luther interpreted in a specific sense:

For in it [the Gospel] the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith; as it is written, BUT THE RIGHTEOUS man SHALL LIVE BY FAITH.

This fear lied in his belief in the justice of God as a kind of retributive justice by which God weighed the merits of a human being versus his/her sin. If the good works outweighed the sin, then one was saved; if not, Luther was doomed. However, at some point (undetermined), Luther began to understand this justice in a different light. Luther declares

…at last I began to understand that the justice of God is that free gift of God (I.e., faith) by which the just man lives…this sentence…should be understood in a passive sense as that [gift] whereby a merciful God justifies us through faith…

Thus, the justice of God became the righteousness of God, whereby God gives faith and salvation to people through Christ. Nothing is earned; grace was freely given by God alone, not by any human authority nor by human will. This righteousness can be understood in the sense of acquittal the human’s status before God has been changed from sinner to Christian, quite literally.

Though this personal revelation delighted and calmed Luther’s soul, he could not begin to realize the impact that these conclusions could bring. One can imagine if a person is justified under God by a free gift, there is no necessity to pray to the saints, nor is there any purpose to doing good works as a way to salvation. The Catholic Church, at the time, offered the sale of indulgences to lessen the time spent in purgatory. With Luther’s doctrine, such a thing was no longer necessary as every man is his own priest. Since this was a source of income for the Church, you could imagine the uproar, if not over doctrine than over money.

In fact, God’s sovereignty over the salvation process removes the need for a hierarchy of the Church. This would mean a drastic loss of power for the Papacy, whose role was both political and religious in the 16th century. As the Pope’s condemnation would no longer be a threat, rulers of various countries could easily violate commands of the Church if they wished. In addition, an undercurrent of German resentment over the Catholic Church emerged, as for years it was thought that the Church interfered within Germany’s a airs. With Luther, however, Germany could resist the Papacy’s political infringement if they so chose. We could call these “unintended consequences”, but I think “earth-shattering change in world affairs fits a fair bit better. A religious power structure which existed for 1500 years suddenly came into question. No wonder it defended itself!

Once Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses at Wittgenburg, the Church knew it had a problem on its hands. These statements, which talked specificially against Church political power, indulgences, and salvific authority, spread around Germany like wild re. Not that Martin Luther knew; he did not suspect that he ventured into a lions’ den right from the outset. As an academic of a sort, he believed he could talk this through with church leaders and possibly endeavor for Reforms. Again, Luther wasn’t a politican, merely a guy with a theological idea; he couldn’t possibly know the number of people he would offend/inspire. He was a normal guy, and so was everyone else not wearing a frilly robe. You can imagine popular opinion went with the regular guy, if not for doctrinal reasons than certainly for religious authority coming from the individual.

Considering these possible factors, it was no wonder that Luther’s attempts at reform were rejected hastily and brutally through a series of poorly-run conferences and meetings which were entirely biased, weighted, and held the near-certainty of conviction and death. The Catholic Church felt that he overstepped his bounds, yet Luther felt compelled to continue. He pursued reconciliation at every turn, yet somehow survived these debacles. Luther was captured by his own follower and touted around Germany while distributed German language versions of the Bible and spreading his message. Of course Luther HAD to accept; he became the face of a theological revolution that sticks with us to this day. He was, in part, responsible for the modern nation-state AND the idea of individuality (as adapted into a Christian context from Renaissance writers).

We see, then, what one man does when he holds the truth, speaks boldly without fear of death or pain, and cannot hold in his convictions. Whether or not you want to condemn the further problems his theological convictions and the Reformation would cause, it started with one man acting in a way that showed depth of conviction and strength. Perhaps knowing “everything” isn’t all there is; perhaps God can tell us what to do, if we ask. Nobody suspects the mustard seed to grow that large, but then it is:

0 And He said, “How shall we picture the kingdom of God, or by what parable shall we present it? 31 It is like a mustard seed, which, when sown upon the soil, though it is smaller than all the seeds that are upon the soil, 32 yet when it is sown, it grows up and becomes larger than all the garden plants and forms large branches; so that the birds of the air can nest under its shade.”

Mark 4

We all exist in the making as little seeds; perhaps we, too, can grow and size to influence our own context and out own people. Jury’s out on that one!