Last updated on July 20, 2013

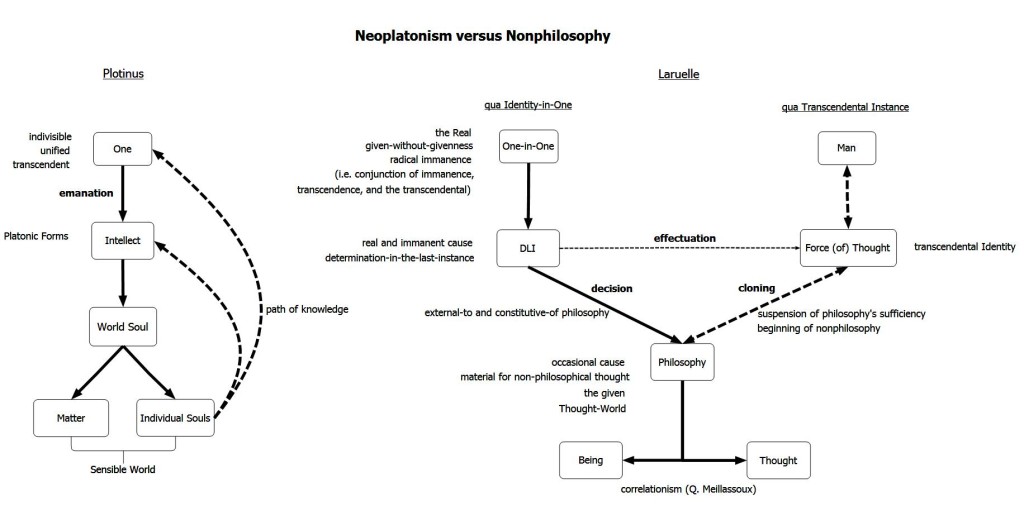

Next, Augustine subscribed to a form of philosophy known as Neo-Platonism. This is different from the world of ideas as described by Plato in an earlier entry of Christian History, even if it shares the same name and similar concepts. However, the ideas are not singular distinct entities; here, a single creator lies in the “middle” or highest part of the hierarchy, while there is a “radiation”, or trickle down from the central body. This means, in fact, that there’s one central Idea which exists as a sort of scaffolding by which every other idea (note the capital I and the lower-case I here) rests. That Idea, in a word, is God.

The person most known for the ideas of Neo-Platonism, Plotinus, combined his Judaic and Pharisee background into the world of Greek philosophy, a combination of Aristotle and Plato which explains the name. This came about nearly three hundred years before Augustine, so it had a long line of adherents before reaching our most esteemed saint here. Unlike Manichaeism, which relied more on wishful thinking than rational thought, delighted Augustine due to its mechanical complexity and explanatory power. Hey, sounds like most good philosophy students, right? Even if you find yourself with a personal motivation towards discovery, that may produce truth!

In any event, Neo-Platonism allowed Augustine to explain evil in a satisfactory way. Because of the outward radiation, evil could not possibly exist as a thing in itself or an independent entity; after all, even Neo-Platonism assumed God’s goodness to some extent. Instead, it is rather the absence, or lack, of good – we flip to see the other side of the coin. Whereas the Manichees saw evil and good as independent forces both battling for supremacy, Neo-Platonism saw evil as an idea and good as The Idea.

It is, for an analogy that makes sense to me at least, like having a filet mignon – if you cook it correctly, it tastes impeccable and excellent. But, if you just leave it out to rot and spoil, it will taste horribly bad, and probably make you sick. So it is with evil, the absence of good. For a more practical example, one could see lust as misdirected love, pride as misdirected humbleness, and a host of other problems. Noting Augustine’s problems with doing the things he did not desire to do, this would fit perfectly! Right?

Augustine continued to seek answers, but he found himself unfulfilled by this philosophical system. Many Neo-Platonists he knew began converting to Christianity, which seemed odd to him – what problems did it solve about evil that Neo-Platonism did not? Wasn’t its conceptions fulfilling enough? He knew it fit, sure, but why did it still seem wrong or lacking in some area? He began listening to sermons by Ambrose of Milan (archbishop of said city which was a center of intellectual study in the 4th century), and it seemed Christianity was a more developed, and much more self-sufficient, form of philosophical thought.

In time, he became intellectually convinced of the truth of Christianity, but he couldn’t take that last step, not least of which because he was in a common law marriage (and the idea for Christians, at the time, was that celibacy was desirable above all else). You can imagine that same situation taking place today – how many still believe that a simple intellectual assent will make them a Christian? I would argue that one must feel these things, not in the straightforward emotional sense, but that one understands their place in the world and the depths of their own depravity. This tells us exactly why the Christian tradition makes Isaiah 14 into a description of Satan: because he is the anti-God, he displays pride. On our side, a Christian must be humble or believe himself justified in everything.

Imagine Augustine in a similar situation. Even if you accept every tenet of the Christian faith, it does not put you in that ultimate position of helplessness, vulnerability, and complete trust – in essence, faith. So we might say Augustine found himself in pride without being prideful (or more like a disguised pride). Still, one day we had that fabulous conversion story wherein he rushes into a garden and hears the words tolle lege, which means “take up and read!” And so he did read Romans 13:13- 14

Let us behave properly as in the day, not in carousing and drunkenness, not in sexual promiscuity and sensuality, not in strife and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh in regard to its lusts.

That was the long and the short of it. What he seems to think, at that moment, was that the missing portion of his Christian faith came from Jesus Christ. He had not clothed Himself in the Savior, which made him unable to see the true beauty of Christianity.

I did not want nor need to read any further. Instantly, as I finished the sentence, the light of confidence flooded into my heart and all the darkness of doubt vanished.

Scripture became that catalyst for conversion. How rarely does that happen in our time? I cannot say for sure, but the persuasion of a preacher or the emotional tinge of a tent revival appear as our relevant “conversion experience”. Augustine came from the highest heights of intellectual thought, yet found that his own knowledge could not cross the different, bridge the gap, or pay the price. As he says in his Confessions:

Thus, since we are too weak by unaided reason to find out truth, and since, because of this, we need the authority of the holy writings, I had now begun to believe that thou wouldst not, under any circumstances, have given such eminent authority to those Scriptures throughout all lands if it had not been that through them thy will may be believed in and that thou might be sought. For, as to those passages in the Scripture which had heretofore appeared incongruous and offensive to me, now that I had heard several of them expounded reasonably, I could see that they were to be resolved by the mysteries of spiritual interpretation. The authority of Scripture seemed to me all the more revered and worthy of devout belief because, although it was visible for all to read, it reserved the full majesty of its secret wisdom within its spiritual profundity.

Confessions 6:5

How can a book appear completely different before and after? How does one’s thought processes change so totally on the whim of one complete event in a life? That is the mystery and the power of Scripture, a double-edged sword of both judgment and repentance.

I guess that’s a pretty good compliment.