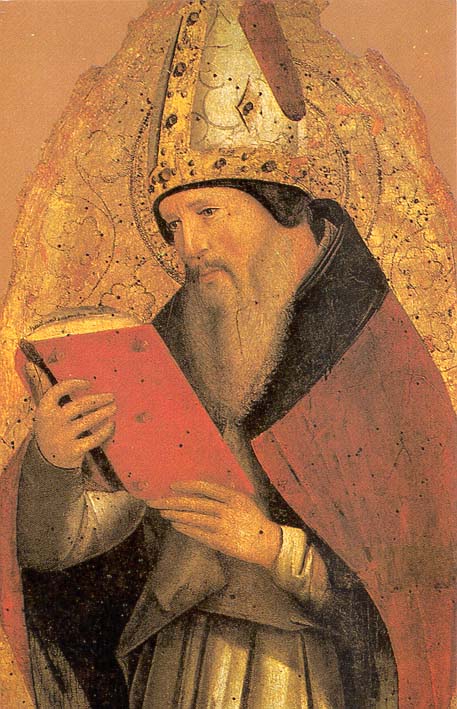

Augustine has, for the most part, been considered the greatest theologian since the Apostles. That might sound like a grand claim, but even a short list of the theological concepts expounded by his writings tell us a great deal of our own history. This is due mostly to his influence in many of the ways Christianity has been conceived throughout the ages; every denomination stole something from his writings. To name a few, analogical interpretations (Catholicism’s number one interpretive method for much of Scripture), the idea of salvation by grace (The Protestant ideal), understanding the Trinity (all modern denominations), the idea of “the true church” (i.e., who has the right beliefs!), visible and invisible church (in other words, those who go to the physical building and/or meeting, and those who believe yet remain outside) and the divide between the sacred and the secular (being questioned in recent years, but perfectly logical in his context), and infant baptism (hoo boy, a contentious issue even now).

Phew, that’s exhaustive. I don’t particularly like reading Augustine (nor do I like Latin translated into English, as a perfectly honest admission), but I see his tendrils far and wide into the Christian faith. Now, of course, not everything was correct (from my view), but the important part was his objective – to truly understanding what he believed, or “faith seeking understanding”, as has so often been said by just about every Christian thinker ever (or Saint Anselm, if you want to be picky about it). To underestimate or even ignore Augustine’s influence would be downright terrible and ignorant from any Christian, so let’s see why he is important, shall we?

Firstly, Augustine didn’t start out as a Christian in any way, shape, or form. He was born to a Christian mother and a pagan father, sure, but he basically rejected those two sets of beliefs from an early age. That might strike one as odd, given Augustine’s predigree, but I think it is important to note: he is just like us. There is a tendency to idolize people even though they themselves would never do the same. To get this off my chest early, Christianity requires a humble heart without pride; Augustine would agree, I imagine! So let’s note that he was not a Christian, and that it required a conversion of intellectual and emotional proportions, along with a long journey, to get him there. This wasn’t a passing fancy; he was intimately familiar with it, yet he rejected it until later in life.

Augustine was originally trained in philosophy (the kind we discussed in earlier installments and Greek/Roman rhetoric – the pride of any Roman citizen with the wealth to afford education.. As such, even though he was preparing for baptism, he found the Old Testament to be rather distateful. He thought that it seemed non-spiritual and made little sense due to “over-literalism” (or, as the Catholics might say now, where’s the evidence for sola scriptura, or Scripture alone?), and there was nothing he could relate to in the writings of various conflicts, wars, struggles, and the like depicted therein. Where did all that evil come from, and how could it be explained? Certainly not by Christianity!

Thus, he reacted by allying himself with a religious faction known as the Manichees. Derived out of Persian Zoroastrianism, the Manichees believed in a good principle and a bad principle (or god, depending). These two aspects of reality are in constant conflict. The physical universe is constructed from the Darkness, while the souls comes from the Light (sounds familiar). This explains where evil, death, and destruction come from, and also denies responsibility from evil deeds – it is evil’s fault!

But, Manicheism was not sufficient for Augustine’s wandering mind. It is an easy solution, Augustine says – what about evil? Is it really just something that happens to me, or do I

really take responsibility for the evil I do? In his own words:

I still thought that it is not we who sin but some other nature that sins within us. It flattered my pride to think that I incurred no guilt and, when I did wrong, not to confess it… I preferred to excuse myself and blame this unknown thing which was in me but was not part of me. The truth, of course, was that it was all my own self, and my own impiety had divided me against myself. My sin was all the more incurable because I did not think myself a sinner.

Confessions, Book V, Section 10

In layman’s terms, Manichaeism makes you feel good, at the cost of presenting no problems to you. You can blame everything on everybody else. Furthermore, in meeting the leaders of this movement, he found they could not allay these concerns. These are easy solutions to complex problems. Thus, Augustine rejected such ideas because they took the human element out of the equation – otherwise, why am I here? Even a Greek philosopher knows that! Further, sin was not created by God, nor co-eternal (as the Manichees thought) with him, but arises from a misuse of free will (which the Manichees denied). If our will is free, we are therefore responsible for our deeds! So yeah, Augustine found this idea insufficient. The early Augustine was promiscuous and even had a wife and child at some point, so he couldn’t possibly believe what felt so contrary to his own life. In this does Augustine align himself with Paul in Romans 7:

14 For we know that the Law is spiritual, but I am of flesh, sold into bondage to sin. 15 For what I am doing, I do not understand; for I am not practicing what I would like to do, but I am doing the very thing I hate. 16 But if I do the very thing I do not want to do, I agree with the Law, confessing that the Law is good. 17 So now, no longer am I the one doing it, but sin which dwells in me. 18 For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh; for the willing is present in me, but the doing of the good is not. 19 For the good that I want, I do not do, but I practice the very evil that I do not want. 20 But if I am doing the very thing I do not want, I am no longer the one doing it, but sin which dwells in me.

21 I find then the principle that evil is present in me, the one who wants to do good. 22 For I joyfully concur with the law of God in the inner man, 23 but I see a different law in the members of my body, waging war against the law of my mind and making me a prisoner of the law of sin which is in my members. 24 Wretched man that I am! Who will set me free from the body of this death? 25 Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, on the one hand I myself with my mind am serving the law of God, but on the other, with my flesh the law of sin.

We do bad things. We do bad things even when we know they are bad things, and that makes us hate those things even as we keep doing them. I can’t imagine a single person on earth who wouldn’t agree with this on some level. It might explain a lot about Augustine that his conversion experience took so long: he represents this archetypal rebellion against God and Christianity, and eventually agreeing with it through personal experience. What a strange thing!

Perhaps this is why his influence goes so far, and he could explain Christian concepts so eloquently? Not that I’ve actually displayed his ability to do that yet, but stay tuned!