Last updated on August 6, 2013

A new contributor this way comes!

Timothy Matthew Collins is interested in collage, the artifact, and its role in design practice through physical modeling and materiality in architecture. As an architectural designer and senior model fabricator at Hillier Architecture (now RMJM), Timothy was involved in several major local and international projects including the East River Science Park in New York City and the Seocho Research and Development Center for LG Electronics in Seoul, Korea.

Timothy has lectured and been a guest critic at several universities, including Carnegie Mellon, Hunter College, Pratt Institute, Stony Brook University, and Parsons School of Design. He has taught architectural design, freehand drawing, and visualization at multiple universities as well. His recent publications include honorable mention in the Storefront for Art and Architecture “White House Redux” design competition and “Architect’s Draw: Freehand Fundamentals” by Sue Ferguson Gussow, Princeton Architectural Press, 2008.

Timothy received an MArch from the Graduate School of Architecture in Florence, Italy at Syracuse University’s Division of International Programs and a BArch from the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at the Cooper Union. He currently teaches 4th year undergraduate design studios at the City College of New York and is a practicing artist whose work has been featured in museum collections as well as multiple exhibitions both in the United States and abroad.

And, apparently, he has an interest in video games, displayed here in full. Without any further ado, here is Mr. Collins’ take on Bioshock Infinite.

Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed nomine diaboli!

[I baptize you not in the name of the father, but in the name of the devil!]

– Herman Melville, Moby Dick or, The Whale

Chapter 113, The Forge, pg. 500.

Bioshock Infinite is a Multi-Universe without Grace. The truly daimonic brilliance of the narrative is its meta-commentary on the illusion of player agency in video games. Indeed, video games rely on the player as a surreptitious accomplice to the developer in order to effectively maintain and perpetuate the manufactured verisimilitude of the digital world (in this case the floating city of Columbia). It is not a game about participating, but rather about reception by the audience. Like any work of fiction, Bioshock Infinite attempts to construct a reality with the perfume of authenticity derived from architecture, politics, and religion. Unlike reality, however, it deposits only one narrative that cannot be significantly affected by choice. Indeed, this is one of the central thematic ideas of the story.

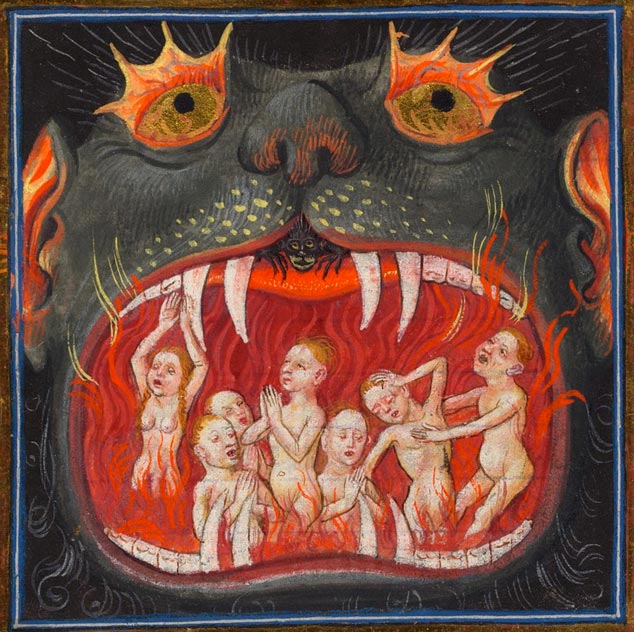

It is possible though, within the panoply of artistically rendered environments and conversations, to extract alternative interpretations that might give us some breathing room to re-collect our own agency in reception. The splendor and glory of Columbia, as well as its explicit religious tropes, could be intentionally misread as a clever and complex cipher of Satan. The Archangel that speaks to Father Comstock could refer to Michael or Gabriel, within the traditional angelic cosmology of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, but it could equally apply to Lucifer: “the shining one.” The prophecy, constantly invoked throughout the game, that Elizabeth is destined to “sit the throne and drown in flame the mountains of man” is essentially a kind of injunction of the Antichrist. The baptism that Booker DeWitt receives at the beginning of the game is itself heretical as it is made in the name of the “founders” of America and the floating city-state. There is the acclamation of “our Lord,” but this annunciation is not technically a particular personage of the Trinity (though it contextually implies the Christian rite). Even the Trinitarian allusions on full display in the architecture of Comstock House, as seen from the Emporia stage, contain this insidious corruption of theology: the Sanctum Sanctorum of the Prophet features the three menacing, disembodied heads of Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin supporting a Panopticon temple in the sky, complete with beaming spotlights for surveillance.

This image of an infernal triune God is repeated again during the climax of the game as Booker is drowned by three Elizabeths, framed in much the same way, with similar facial expressions to the Demigod founding fathers. Elizabeth herself is emblematic of the gilded deception. Although seemingly a “regular” woman, she is essentially a Magician. Though explanations abound as to why she is able to open tears, there is no satisfactory mechanic in the narrative to explain why her powers are a kind of “wish fulfillment,” and how, more importantly, she is capable of creating new universes. But, that contention aside, the game’s true diabolical will is on full display in their ultimate motivation, which drives Booker and Elizabeth through the Mulitverse: not just killing every Zachary Hale Comstock in every single universe in which he ever existed (a very special kind of genocide to be sure), but undoing his very creation, his essence, nullifying his being: a work only a god could achieve. Their main drive is an obsessive fixation on vengeance.

This is made even more problematic by the moral paradoxes that are latently presented, but left entirely unaddressed by the characters. These include the questionable morality of smothering an innocent baby in its crib. Even if that innocent child grows up and becomes a murderer, there is still some ambiguity as to the righteousness of the action which none of the characters ponder. More obviously, if there are multiple versions of Comstock, some of them may be good and decent men who do not deserve the wrath of Elizabeth the Time Lord. Critics will point out the oft-repeated quote about Constants and Variables: that not all decisions lead to different outcomes and there are certain typological constancies throughout the multiverse (“There’s always a lighthouse, there’s always a man, there’s always a city”). But this is directly challenged by the game itself through the spectral Lady Comstock. In their final exchange, Elizabeth concedes that this version of Lady Comstock is alive because she probably never met the Prophet in the universe she came from. Lady Comstock ruminates that it is also possible she “saved him,” implying that fundamentally different outcomes might be possible in the different universes. At the time, Elizabeth is unsure if if is even possible and, although she obtains her true potential and can “see all the doors and what’s behind all the doors,” comments no further on the possibility that some Father Comstocks in some universes might be innocent and worthy of being spared.

This leads to the infernal apotheosis of the game. It is one thing to shoot an opponent in the face, it is another thing to play God with existence (either one’s own or others). Elizabeth engineers creation while Booker tries to find “redemption” through an application of will alone (by allowing himself to be drowned as a willed sacrifice to reverse the events of the game). This is the quintessence of putting oneself on the same level as God and is, in fact, not redemption by definition, which relies on the gratuitousness of God’s love in communion with our own and one another. One might object that Jesus himself also allowed himself to be crucified, to “fulfill” the Father’s will. However, Christ endured his Passion precisely so that he would not sacrifice his relationship to the Father, and not simply to solve the struggling and contingent world by taking away our own accountability: “My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me; yet, not as I will, but as You will.” (Green, Jay P. Sr., ed. “The Gospel According to Matthew 26:39.” In The Interlinear Greek-English New Testament, vol. IV of The Interlinear Hebrew-Greek-English Bible, pg. 81-82. Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.)

This is our struggle: to reconcile our own wills with God’s, to bring them into alignment, not through an irresistible and forced compulsion, but through our freedom as creatures. Neither Booker nor Elizabeth really receives the blessing of the love they might share now, in light of all they have gone through together, on this journey that is the game. Instead, we have played the entire game so that the events in the story can never happen, thus nullifying, not redeeming, the sacrifice. Rather than Christianity, the game perfectly renders the Greek daimon: the mechanistic administration of a universe whose roots can be traced to both the concepts of “demon” and unalterable destiny that Christian Theology explicitly subverts.

Bioshock Infinite is an incredibly rich and provocative work that touches on many important themes, albeit incompletely presented and sometimes caricatured, However, this provides us, the gamers, an opportunity to assert our own agency in judging and interpreting the premises of the avatars we pretend to control, instead of passively receiving and mindlessly following the orders on screen. Grace is, in fact, such a dialogue, between the humility to receive the blessing and the will to understand it. The extreme of either hyper individualism or fatalistic subservience is a dangerous hyperbole of human behavior, which is far richer in the spaces where it does not fit the code.