Last updated on July 27, 2013

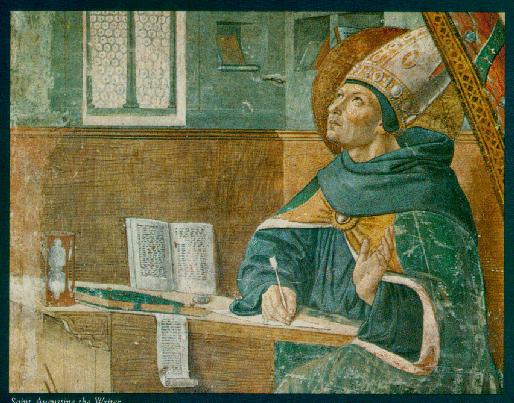

There is a lot of Augustine on this website! I imagine that should speak to his importance AND how many theological debates in which he participated still loom over us today.

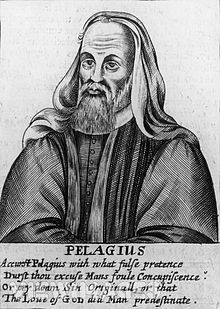

At the same time that Augustine dealt heavily with the beliefs of the Donatists, he also came into conflict with another, probably more familiar “faction”: the Pelagians. Pelagianism, a way of thought sparked by a bishop named Pelagius (no surprises there) was a belief that a Christian could lead a life without sin. Christians needed no help from God other than instruction from Scripture and Jesus Christ’s example. Adam’s fall just introduced death and the example of sin; it did not make sin inevitable for everyone and everything. Rather, our own mindset prevents us from living the lives God wants us to live. In a way, it strikes a “self-help book” tone; subsequently, writers such as Peter of Abelard would take up the Pelagian mantle only to find themselves on the wrong side of Christian doctrine.

Why do most Christians reject such a line of thought? Augustine provided a rigorous opposition to the ideas of the Pelagians. He came to see that faith itself is a gift from God, the work of HIS grace, not ours. It is not a situation where, in fact, you make the first move regarding the human-deity relationship. Instead, the connection remains entirely a gift of God. Imagine it like this: you don’t get to choose the gifts given to you, if anything, gifts aren’t gifts unless they’re chosen by someone else who took the time and the thought to pick that gift out. In God’s case, the gift’s perfect and suitable for everyone. As 1 Corinthians 4:7 says,

For who regards you as superior? What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as if you had not received it?

At the time, Augustine’s idea that God’s chosen elect were given this grace wasn’t controversial at all (as the copious references to Romans 9:16 demonstrate). Salvation is all of God’s grace, the beginning of it as well as the continuance in a believers’ life. God’s mercy alone gives it, not our power. All sin in Adam, and are guilty/biased towards sin. He believed this bias existed in the form of concupiscence – we sin inevitably, yet freely. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak, so to speak, because we can freely will, but not to will what we ought to do. It’s an interesting contrast that, at the same time we have the freedom of will, that same will’s constrained by our very nature. We miss this, more often than not, when we try to do good things.

Augustine came to a fuller explication of these views precisely due to a re-examination of his own conversion experience. He did not choose it – in fact, he had wanted to convert so badly that he philosophically accpted Christianity. Even so, he could not bridge the gap between “saved” and “unsaved” through mere assent; something else needed to work itself out. So it was that Augustine could only view grace as a special gift:

You move us to delight in praising you – for you have made us for yourself and our hearts are restless till they find their rest in you…I will now call to mind my past foulness and the sins of my flesh, not because I love them, but because I love you, O my God…In [the books of the Platonists] I read…that in the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God…but I did not read there that the Word became flesh and dwelt among us…I longed [to serve God alone] but was bound, not with the iron fetters of another, but by my own iron will. The enemy controlled my will and with it had made a chain for me and bound me. Lust had grown from a perverse will, habit had come from indulgence in lust, necessity was the result of not resisting habit…Give [the grace to do] what you command and command what you will.

Confessions

In this sense does God provide grace, in several kinds. First comes operating grace, that is, prevenient, preceding the good will. It always achieves its end, converting the will. In a weird way, God’s grace seduces the will into right conduct, to which the soul (made by God) responds in great happiness. Once the conversion happens, grace can cooperate with the soul. Cooperating grace is neccessary because the will remains weak to the whims of sin, and without God’s help we would soon lapse. However, to run the race to the end, we need the gift of perseverance.

[God] extends his mercy to [people] not because they already know him but in order that they may know him. He extends to [people] his righteousness, by which he justifies the ungodly, not because they already are but in order that they might become upright in heart…If a commandment is kept through fear of punishment and not for love of righteousness, it is kept slavishly, not freely, and therefore is not [truly] kept at all. For fruit is good only if it grows from the root of love…That man has progressed a long way…in righteousness…who has discovered by that very progress how far he is from the perfection of righteousness.

The Spirit and the Letter

This is why Pelagianism doesn’t work – it operates on the idea of human capability, when we are not capable without God. If sin is sin, then sin cannot be fought – we can only lose under our own power. Otherwise, why should Christ come at all? As usual, we see a common dichotomy between Christians and others – proper doctrine does, in fact, engender a defense of faith itself. A wrong perspective yields a destruction of uniqueness and truth!

In this case, we see the fault of emphasizing human action in deference to God’s own actions. There’s the tendency to think that God only acts when I will and only affects me, but He currently works within every living human being on earth. There’s a grand tapestry on display, and God’s grace, a free gift, is distributed to all. It is this sense that makes us humble in our works, knowing that they contribute just a little bit to the Kingdom of God.

God allows us to participate in this Kingdom-building in our own ways; He knows our limitations and responds accordingly. He gives us promises throughout Scripture, and then expects us to remember those promises. In light of God’s grace, we can become effective in our faith, both regarding ourselves and to others. I imagine Augustine was thinking of 2 Peter 1 when he wrote against the Pelagians:

To those who have received a faith of the same kind as ours, by the righteousness of our God and Savior, Jesus Christ: 2 Grace and peace be multiplied to you in the knowledge of God and of Jesus our Lord; 3 seeing that His divine power has granted to us everything pertaining to life and godliness, through the true knowledge of Him who called us by His own glory and excellence. 4 For by these He has granted to us His precious and magnificent promises, so that by them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world by lust.5 Now for this very reason also, applying all diligence, in your faith supply moral excellence, and in your moral excellence, knowledge, 6 and in your knowledge, self-control, and in your self-control, perseverance, and in your perseverance, godliness, 7 and in your godliness, brotherly kindness, and in your brotherly kindness, love. 8 For if these qualities are yours and are increasing, they render you neither useless nor unfruitful in the true knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these qualities is blind or short-sighted, having forgotten his purification from his former sins. 10 Therefore, brethren, be all the more diligent to make certain about His calling and choosing you; for as long as you practice these things, you will never stumble; 11 for in this way the entrance into the eternal kingdom of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ will be abundantly supplied to you.

Phew! There’s Augustine for you; now onto something else next time.