I’ve always wondered why some authors fade into obscurity, while others remain in human culture for generations upon generations. Sometimes, they find themselves revived by later civilizations who find their works as innovative, fresh, and engaging as when they were first written. In most cases, it seems there’s a particular movement associated with their continual prosperity. In the rarest of exceptions, they’re merely forgotten for reasons unknown…or, perhaps, less know then we’d like.

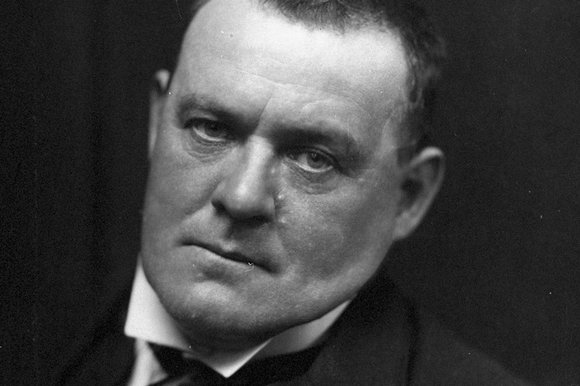

One of those men/women, and one of my favorites, was the great British essayist/novelist/sometimes Catholic apologist and theologian Gilbert Keith Chesterton (heretofore referred as “G.K.”, as he’s most often known). He displays a wit and a hilarity I’ve rarely seen in an author dealing with complex issues; it would not be a stretch to say C.S. Lewis read his works extensively, if the general audience of both are taken with any seriousness.

One of the best of these, and probably less know than “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” is “The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare”. As much an interesting spy novel as a religious allegory, it’s equally hilarious, fun, and altogether serious at the same time. A hallmark of Chesterton’s work comes from its inconspicously paradoxical nature – Christianity, in its own way, represents equal parts judgment and love which somehow hold together in tension. If I’m not mistaken, that’s an official doctrine of the Catholic Church as well – no surprises. The “metaphysical thriller” requires a lot of thought and work to understand; I’m honestly going to read it again, because it does mean SOMETHING beyond a cursory glance. Written when Chesterton saw only bad and evil in the world, he wrote it as a response that there must be some good – or that, in the spirit of Augustine and Aquinas, that evil was not a thing in itself but a blemish on good. In his words:

The book was called The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare. It was not intended to describe the real world as it was, or as I thought it was, even when my thoughts were considerably less settled than they are now. It was intended to describe the world of wild doubt and despair which the pessimists were generally describing at that date; with just a gleam of hope in some double meaning of the doubt, which even the pessimists felt in some fitful fashion.

It’s all the more interesting when you consider the central plot of the book revolves around a secret underground anarchist society where nobody’s actually an anarchist. Which makes no sense, mind, but the reveals and the characters don’t seem to notice or care. Since it’s available on every eBook format on earth, you may as well read this short little book. Then come back!

Well? Come on, you think I’m horrible enough to make you read a whole book to understand a thousand word blog entry?

The central conflict of the book, nevertheless, comes from this anarchism where everyone appears as one, but isn’t really. The conflict of Chesterton’s time was religion versus modernism; the latter saw Christianity as an outdated construct unsuitable for the mind of “modern” men. Many apologists and otherwise rose up to defend their faith (even some recently converted, as well; it was quite an intellectually tumultuous time). All in all, it was a rather friendly debate; each side respected the other as a genuine human being, even if they disagreed on the big questions of their time. Everyone lived under mostly conservative, traditional values. No one was all that “different” from one another, as they shared a common cultural heritage.

This may seem an odd thing, but it’s important to understanding WHY nobody seems to know who Chesterton is in the modern era, nor his “partner in crime” Hilarie Belloc. Simply put, such religious people who lived in the time of Modernity (the cultural movement, not as in modern times) got the whitewash from academics and the public at large. Rather than engaging their works, they discredited them by labeling both as anti-Semites (which, as I can tell you, they most certainly WERE NOT). And, after World War II and the Holocaust, who could blame anyone for not wanting to associate themselves with these authors, right? This kind of foul play happened to many authors from around the world; name-calling, accusations, and unfounded claims win the day in the public eye, rather than the true story.

No longer does the debate between religion and “culture”, as such, seem a friendly rivalry. Rather, the dehumanization employed upon a number of dead authors, writers, speakers, and whoever continues even today. As the late Christopher Hitchens says of Aquinas:

Aquinas half believed in astrology, and was convinced that the fully formed nucleus (not that he would have known the word as we do) of a human being was contained inside each individual sperm.

In any case, that’s either egregiously wrong (Aquinas believed in the scientific traditions of the time; he wasn’t opposed to it, and so wouldn’t anyone in a university at the time) or just plain insulting for the means of getting a laugh. And, let it be noted, a dead person cannot defend themselves. The same goes for the religious; we tend to dismiss each other, simply out of outright hatred rather than true, meaningful conversation. Of course, Christians should take the first step in that case, but why should we expect a positive response? Argument doesn’t have to be of the spittle-inducing kind. Don’t be provoked, and don’t say things you’ll regret. The first step in dehumanizing a person comes from avoidance of the real issue. Ephesians 4 tells us directly what to do:

25 Therefore, laying aside falsehood, speak truth each one of you with his neighbor, for we are members of one another.26 Be angry, and yet do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger, 27 and do not give the devil an opportunity.28 He who steals must steal no longer; but rather he must labor, performing with his own hands what is good, so that he will have something to share with one who has need. 29 Let no unwholesome word proceed from your mouth, but only such a word as is good for edification according to the need of the moment, so that it will give grace to those who hear. 30 Do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, by whom you were sealed for the day of redemption. 31 Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you, along with all malice. 32 Be kind to one another, tender-hearted, forgiving each other, just as God in Christ also has forgiven you.

Loving your neighbor and having a friendly debate about important issues don’t have to be exclusive.