Last updated on November 5, 2013

Let’s take our criticism further. What makes God of War “nihilistic”?

To define: it is the idea that life is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value. But I think true nihilism takes the whole concept one step beyond, as in Nietzsche’s work: we create our own value. Few true “nihilists” and atheists are willing to take it that far. I applaud those which take the concept to its negative conclusion, as they have the fortitude to live in a world without values, restraints, or compromises. As Nietzsche would say:

A nihilist is a man who judges of the world as it is that it ought not to be, and of the world as it ought to be that it does not exist. According to this view, our existence (action, suffering, willing, feeling) has no meaning: the pathos of ‘in vain’ is the nihilists’ pathos — at the same time, as pathos, an inconsistency on the part of the nihilists.

The true nihilists injects meaning into whatever they wish – whether it be murder, sex, violence, you name it. Most would speak of the “higher pleasures” – after the initial high of “freedom” has worn off – but the end result leads to what they want to do. There’s no higher meaning in such a world, as the individual becomes the higher meaning. In God of War, YOU are the higher meaning. Kratos, as the God of War, becomes a cipher for you – your rage, aggression, and power. By playing a role in a vast Greek tragedy, you become the wielder of vast powers to kill, maim, and destroy. It certainly fits the name, in any event.

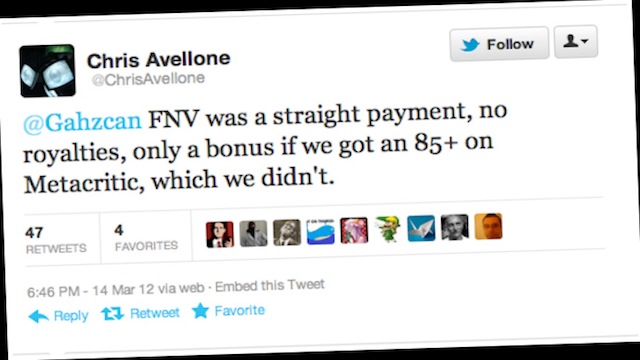

As a power fantasy, then, a chance to create one’s own value without the constraints of society’s reckoning, God of War becomes one of the most effective murder simulators out there. If you think this has no relation to the series’ excessive scoring on every media aggregate, you’re kidding yourself. Browsing Metacritic’s ratings, we can see that the main games in the series received universal acclaim – none of the games in the main series scored below a 90. Few magazines were willing to buck a trend while it’s hot – if you were making money, would you? I’m surprised Edge Magazine gave God of War II a 7/10 – although, still, a negative review plainly doesn’t exist in any major media outlet. Whether by their personal feelings for the game itself or advertising dollars, something remains amiss. To declare a grand conspiracy, obviously, doesn’t make sense, but there’s a good reason why the series continues its journey into the good graces of just about everyone playing video games.

From a logical standpoint, critical reception alone does not a good game make. Let’s imagine a pretty obvious counter-example: everyone is giving murder a 9.0 or above rating on the “moral things to do list”. So, everyone goes out and murders everyone they don’t like due to some arbitrary standard. Something must definitely be great about murder if everyone really likes it. Majority opinion, you might say, doesn’t hold any special revelation regarding God of War. That something is, in fact, liked by a majority of people does not make it great. Nor does a number score – I honestly don’t care about review scores (excepting Theology Gaming, of course) in the same way I don’t care about the number/stars system of any review. It’s merely a summation of the written review in most cases.

There is one thing setting God of War apart: the ambiguous category of “experience”. The traditional definition of experience is a particular instance of personally encountering or undergoing something. How hilariously vague – this could be applied to literally anything, let alone video games. So what is this an experience of? God of War’s combat, as described in Part 1, is quantitatively worse than most of the premier action games of a similar vein. It’s getting a pass from the “experience”, not the mechanics in themselves. And what is that experience, really?

To be overly reductive, it’s pressing buttons and having things happen on screen. Hit stuff, maybe dodge once and a while, and then the game rewards you for your “effort”. Is that all we desire, that a simple string of smashing the same buttons over and over again provides some kind of visceral thrill? Sure, God of War has multiple difficulty levels, but what reviewer was ever looking for said challenge? Rather, it’s the feel of the button presses that makes the game come alive and convinces nearly ever person “I LOVE this game”. Not merely like; in any other case, we’d have a mediocre action-adventure on our hands. Yet, for some reason, God of War convinces people they’re playing a great game.

Andrew Toups from ActionButton.net has a possible explanation from his God of War 2 review:

But the real reason God of War 2 (and by extension, I suppose, its predecessor) is a horrible mistake from the ground up is simple. It starts with the duck roll in Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. The duck roll, if you don’t recall, is the default function of the context-sensitive action button which causes link to perform a brief forward somersault that provides a quick, oh-so-slight boost of velocity to Link’s jog. The duck roll is useless. It gives you no advantage in combat, nor are there any puzzles or setpieces that require you to use it — it barely even decreases the amount of time it takes to walk. It is entirely extraneous, yet at the same time it is essential to keeping that game from becoming monotonous. Why was the duck roll — which, bizarrely, is called “attack” on the HUD, despite not actually ever doing any damage — included in the game, then?

Well, the duck roll exists so that the player has something to do while walking through Hyrule field. It provides the same basic “fun” response as pressing A to make Mario jump does in Super Mario Bros. Take this away, and the game does not fall apart — however, suddenly the time it takes to reach the next destination seems to dramatically increase. Those dragging moments caught between objectives, trying to find the next point to move the story forward, become all the more excruciating. The game’s design, which is already pedantic, patronizing, and perverse, becomes much more transparently so. Without the opiate of the duck roll, the lie that the game is built on becomes clear..

…What does this have to do with God of War? It’s only a minor exaggeration to say that every button press in this game triggers a duck roll. It’s an exaggeration only because every little action does have a specific in-game use — but those uses are, 95% of the time, either spoon-fed to you in ham-fisted environmental puzzle, or just entirely meaningless. For the first 25% of the game, nearly every fight can be won by mashing the square button. As more “difficult” enemies appear, nearly every fight can be won by mashing the square button and occasionally flicking the right analog stick to dodge. By the end of the game, you may have to block every now and then. Boss battles are about as involving, only interspersed with occasional Quick Timer Events and with a greater time limit between health recharges. When you die, you restart and flick the dodge stick a few more times per square button push, and bam, you’ve won. The game is constantly throwing heart stopping scenery and violent, over-the-top setpieces at you to distract you from this fact, so you never notice all this. But it’s happening.

There is is – God of War is full of meaningless mechanics that are augmented by the animation, by the magnificent set design, by the fluidity of the animations as they provide a cacophony of satisfying slashing and/or smashing sounds that repeat over and over again. It’s satisfying that weird nervous urge in yourself that what I’m doing has meaning, for God’s sake, and I’m not playing this game just because it makes me feel good to beat the ever-living crap out of everything in sight. Lo and behold, the avatar Kratos shares my sentiments!

In fact, God of War emasculates. It presents a false vision of what video games can truly be – fun, innovative, entertaining, challenging, meaningful. When we take every base element and blend them together, you get the perfect product that appeals to every base desire…but not a video game. It’s not even the working of a focus group. It’s worse than that – it’s feeding an unknown addiction to kill stuff without remorse and without mercy, and feel great about it without the hangup of challenge. It makes one invest meaning in the meaningless – and for that it’s a shameful exercise in excess for its own sake, nihilistic to the core.

In the words of Charles Stanley, experiences like God of War are powerful in their deceptive offer of immediate pleasure without penalty. And that’s why so many invest themselves in such a world.

That’s not what we were made for. That’s not God’s desire for human beings to be the masters of their own domain.

3 For this is the will of God, your sanctification;that is, that you abstain from sexual immorality; 4 that each of you know how to possess his own vessel in sanctification and honor, 5 not in lustful passion, like the Gentiles who do not know God; 6 and that no man transgress and defraud his brother in the matter because the Lord is the avenger in all these things, just as we also told you before and solemnly warned you. 7 For God has not called us for the purpose of impurity, but in sanctification. 8 So, he who rejects this is not rejecting man but the God who gives His Holy Spirit to you.

Although 1 Thessalonians refers to sexual sin, it’s the same general problem. God of War gives us the very definition of impurity in video game form.