Last updated on July 30, 2013

- Part 1 – Nobunaga’s Ambition and a Short History of Koei

- Part 2 – You Can’t Know Everything

- Part 3 – Playing Nice With Others

My relationship with Koei games went from “love” to “hate” somewhere around the time Dynasty Warriors One Billion (not a real title) came out. Certainly, I enjoyed the first few games in the series – I remember loving Dynasty Warriors 2 to death, and enjoying the third game with its brand of fogged-out co-op. Still, a developer can only create the same game with minor tweak so many times. What entry are we on now? Number eight? Not including the Samurai Warriors/Strikeforce/Warriors Orochi/Empire/Xtreme Legends/Fist of the North Star expansion packs/spinoffs? Clearly, there’s too many of these games out there! Koei needs some fresh ideas (other than adding zombies into things).

Maybe they need to return to their roots as the premier Japanese historical simulation strategy game company. Or, barring that, a return to their “adult home software days”. Actually, I take that one back.

So yes, Koei made “adult” software; this provided them the seed money for Yoichi Erikawa to indulge his historical impulse into actual PC games. At least in the early days of the computer gaming market, Japan had a thriving scene of developers each seeking to use the various machines on hand. Remember, the lack of a common operating system or graphic user interface (or GUI) made that task quite a difficult one, so imagine dipping your toes into a tumultuous marketplace with no set standards. Yoichi, then, developed a programs called KOEI DOS that would allow their games to run on any of the computer platforms currently out in Japan at the time. That breatkthrough made Koei’s entry to the video game market much easier than it would have been otherwise. Now, they could focus on the games.

Yoichi’s wife Keiko ran the company (this also explains why she’s worth nearly a billion dollars) while he put himself to work developing the first Koei game: Nobunaga’s Ambition. For 1983, the game attempted a highly ambitious mix of economic development, real-life diplomacy, complex warfare tactics, and human resource management rolled into a single game experience. Frankly, nothing of the sort had emerged before in the video game scene at this rate of development, and 1983 demonstrated few choices in the genre. I imagine someone more knowledage than I could imagine one, but combining military with political management certainly was a rare sight on the video game scene. It may not look like much now (and this NES port looks worlds better than their PC games), but Nobunaga’s Ambition nearly created a genre unto itself.

Perhaps this is due to Yoichi Erikawa’s personal ambition. For whatever reason, Yoichi did not wish to associate his name with the product in question; he took a pseudonym (more well-known than his real name in the West), Kou Shibusawa. Apparently, he named himself after a Japanese industrial of the 19th century named Eiichi Shibusawa. Called “the father of Japanese capitalism”, the Shibusawa name is synonymous with the foundation of Japanese banks in the Western style (based on joint-stock holding), creating hundreds of corporations, the Japanese Chamber of Commerce, and donating millions of dollars to community help projects. In a phrase, he represents the ideal of the free enterprise system in Japan, a cooperation between private sector compassion and public help. He didn’t even own a controlling stake in any of the corporations he founded, a rarity. How else could you respect such a figure except by naming yourself after him? The industriousness shows in the Nobunaga’s Ambition series, truly.

Not only would it represent a landmark strategy game, but it would also contain actual historically accurate information. You could, if inclined, look up the names of any of these figures and find them in the history books. Koei does fudge the history a bit for the purposes of fun (not including their more recent output), but it does make for a better game. Still, imagine that you’ve got no idea what is happening here, nor any knowledge as to Japan’s internal warfare. How does a Western audience respond to such games?

We can take Computer Gaming World’s response as a primary example:

One may transfer soldiers between fiefs, go to war, increase taxes (which causes a decrease in peasant loyalty which may lead to rebellion), transfer rice or gold to another fief, raise the level of flood control (which decreases productivity), make a non-aggression pact or arrange a marriage, cultivate (which increases productivity, but decreases peasant loyalty), use a merchant (to buy/sell rice, borrow funds, or purchase weapons), recruit for the military (soldiers or ninja), train the army (which increases fighting efficiency), spy on a rival, expand a town (which increases taxes collected, but decreases peasant loyalty), give food/rice to peasants/soldiers (to raise morale), steal peasants from rival daimyos, allocate military strength, recuperate (even a daimyo can get sick), turn over a controlled fief to the computer for administration, or pass a turn (hint: when one has no idea of what to do, train the troops.)

All of that can be done in any given turn, provided you have the resources to do it. If none of that makes any sense to you and your head is spinning at the possible concequences of any action, read the manual. Video games originally functioned like a conduit for imagination and discovery; the manual would help you understand all the mechanics that the game had no time nor money to explain. They gave you the tools, and the player discovered the optimal strategies over a long, long period of time. In Nobunaga’s Ambition, this meant a careful balance between political diplomacy, military aggression (after all, that’s the only way to unify Japan!), economic growth (so you can build armies AND make your citizens happy), and simply building up your province. All these various resources affect one another, so there’s no all-out focus on anything; like any good leader, you need to know your stuff.

Can you focus on one area in deference to the others? Sure! It’s entirely possible to play as a complete warmonger, beating every daimyo (or fief leader, as we may call it here in the States) into submission while neglecting your people and your natural resources. However, like in real life, the engine of war requires lots and lots of money and reapable resources. If another daimyo resists your attempts at conquest, you may find yourself without the necessary infrastructure to continue the fight. Transporting troops AND training them takes time, and feeding them takes food. Drafting new men requires a happy populace willing to serve their great leader in the cause of unification. In other words, the risks and the rewards, while not clear at first, align with real life more often than not.

In that sense, Nobunaga’s Ambition forces a lot of waiting and forethought. The game’s pacing, glacial at best, requires a patient and steady mind willing to plan in advance and take advantage of the AI’s faults and/or stupidity. They can, and will, attack you at the worst of times, forcing quick adaptation and decisionmaking. Provinces/fiefs can rebel, and even officers who’ve served you forever may turn sides in the heat of battle. Clearly, you can’t cover every single contingency (and more of them, as the series developed), but the impossibility to predict future events (like, hey, history!) lent a lot of variety to every game.

Of course, for a child living in America in the early 1990s, how exactly would you find this information without the Internet? Hey, remember books everyone? Those were cool! A trip to my local library after playing Nobunaga’s Ambition would yield vast knowledge of a culture completely dissimilar from my own. It almost felt like a piece of lost history; America barely existed in 1555 while an entire nation, highly developed internally in both military and diplomatic affairs, erupted in a civil war that continued for nearly a hundred years. And this wasn’t even the first series of wars Japan experienced. It’s an eye-opener for sure.

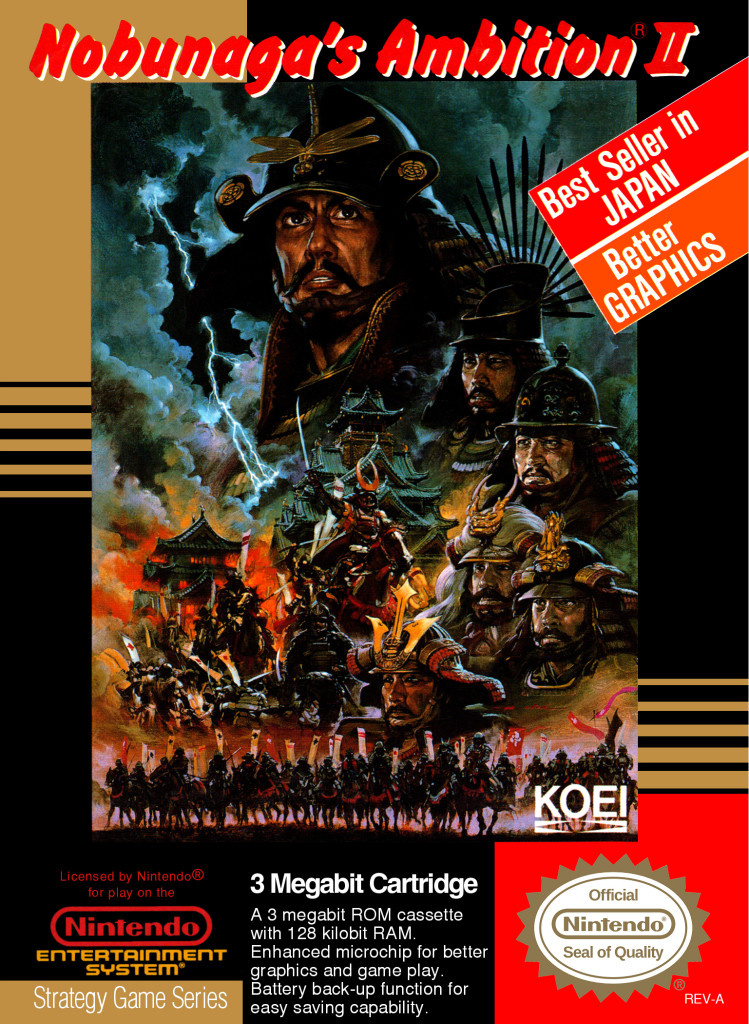

Koei became known as THE historical simulation company through the ’80s and ’90s due to these factors. They went on to develop many, many more games in Kou Shibusawa’s Historical Simulation Series, including Genghis Khan, Bandit Kings of Ancient China, and even a few titles located in other historical contexts (Liberty or Death comes to mind as the Revolutionary War Koei game, as well as L’Empereur, their Napoleonic War games). Nobunaga’s Ambition made it possible for them to create more intricate experiences, and several sequels (up to the 13th entry, only available in Asian regions) followed.

If there’s any one factor that dampens the experience, it’s the AI. If you program a complex game system that doesn’t have a simple solution, your AI must rise up to the task or cheat. This is why, as competitive multiplayer games got more complicated, the AI got worse; unless there’s a strict answer to every situation when playing like a human, the AI must cheat to provide a challenge to the player. This is equal parts frustrating and challenging. On the one hand, the game should force you to play to the best of your ability. On the other hand, we usually feel cheated when a computer player suddenly attacks us with a force he didn’t even have a turn ago.

That’s the perennial problem with complex strategy games, and that’s no more apparent than in Civilization V, where the AI acts incredibly bad in all combat situations and plays in the most bizarre way possible. Sulla explains that pretty exhaustively on his website, but the point stands. We feel the impact of an impartial game system as a personal offense; how many people rail against “rubber banding” in most racing games, or hilariously powerful end bosses in SNK games? Of course, it’s merely a game, but in real life the result is rather the same at this injustice:

My brethren, do not hold your faith in our glorious Lord Jesus Christ with an attitude of personal favoritism. 2 For if a man comes into your assembly with a gold ring and dressed in fine clothes, and there also comes in a poor man in dirty clothes, 3 and you pay special attention to the one who is wearing the fine clothes, and say, “You sit here in a good place,” and you say to the poor man, “You stand over there, or sit down by my footstool,” 4 have you not made distinctions among yourselves, and become judges with evil motives? 5 Listen, my beloved brethren: did not God choose the poor of this world to be rich in faith and heirs of the kingdom which He promised to those who love Him?

A strategy game, more often than not, provides a similar motivation. At this level of abstraction, you won’t see warfare as a brutal exercise but as a means to achieve the ultimate goal of peace (i.e., win condition). If the game’s going to cheat or be impartial (which it usually does), we’ll beat it anyway and bring he/she/it to justice. That’s a pretty strong motive. After spending so long with the game, it becomes a rather personal affair; the more time you invest, the more engaging it becomes as you learn the rules and learn to manipulate your way to victory. For justice, of course! Perhaps you think my connection here seems a little far-fetched, but I’m not above claiming that video game can provoke emotions – they just usually contain throwing of controllers and/or mice as well as feeling slighted in some way. Nobunaga’s Ambition can do that to you if you’re not willing to play by its rules. Those rules are magnificent, complicated, and well-designed.

However, Nobunaga’s Ambition isn’t their greatest series; it may have sparked the company’s creative period, it was Romance of the Three Kingdoms that really set them on the map. Well, at least for the boorish Americans who actually played Koei strategy games.