Last updated on January 22, 2013

Nintendo did not have an RPG to its name prior to 1996. Someone will point out my lack of knowledge in this area, but I can’t think of one or even find one. The majority of NES RPGs were made by Square or Enix – any derivatives were ports of CRPGs made into NES games. Nintendo didn’t need to make their own, as their were plenty such games going around the block. Still, when the opportunity arose, you could imagine that Nintendo would take full advantage. Hence, the creation of a tiny game studio and its unique idea change the course of game history.

You don’t hear the name Satoshi Tajiri come up in conversations about gaming luminaries; why doesn’t the director of the Pokemon series get his due? I imagine it’s due to a perceived “lack” of innovation from Western journalists. Of course, most see the constant iterations of Pokemon games that have come out for the last fifteen years or so, see the “same old thing”, and move on. But that same Darwinian evolution takes its time to refine the game in subtle ways on every aspect of the design. This has a great deal to do with the initial inspiration for Tajiri’s game design and the guiding hand of Shigeru Miyamoto.

Satoshi Tajiri was just a kid who loved insect collecting – perhaps his Asperger’s has something to do with his nickname, “Dr. Bug”. He wasn’t great at school, nor was he a particularly bright student. In fact, he almost didn’t graduate from high school. Becoming fascinated with video games, he eventually went to a technical institute and got a degree. Even in adulthood, his interests continued to linger; thus, he created a magazine called “Game Freak” in 1981 at the age of 17. Game Freak was the kind of “fanzine” that comes in the form of “doujin” conferences nowadays; it was hand-made and stapled together. Ken Sugimori, an artist, saw this magazine in a shop and wanted to get involved. Together, they operated the magazine for five years. They perceived a decline in the quality of video games, so much so that Game Freak became a genuine development studio. They made a variety of simple games, but the idea for Pokemon came in 1989 when Tajiri saw the Game Boy and its Link Cable. Lamenting the loss of his hobby due to the increasing urban development of Japan (not much greenery!), Tajiri desired to recreate this childhood experience for the masses.

The process wasn’t easy; Pokemon took six whole years of development time, released roughly ten years after Dragon Quest’s arrival. Tajiri found his way to freelance work with Nintendo; he aided work in the first few Zeldas games. Impressed by Tajiri’s work, Nintendo executives were willing and open to seeing his new idea – Pocket Monsters, the abbreviation better known than the original name – and giving him time and money to develop it. Time and again, the small game studio faced innumerable problems from design to money to exhaustion; Tajiri was known to work several 24-hour days in a row – not that he still doesn’t do this to find inspiration. Nintendo, as you probably guess, has an eye for polish and perfection, and this made the process much more difficult while also aiding the final product in the end.

Ken Sugimori must have obsessed over the quality of the creatures in the game itself; he (above) designed AND drew all 151 Pokemon as the sole conceptual artist. That’s a task for any man! This was a labor of love, no doubt about it. Game Freak nearly went bankrupt in the process (even with Nintendo’s help!), but eventually received an investment from Creature, Inc. to finish the game (who now owns a large portions of Game Freak and the rights to Pokemon in some measure). Even then, the Game Boy was thought to be on its way out of the console market; this was the time of Playstation and N64, not 8-bit black and white Game Boy games. Pokemon spent so long in develop that its intended audience had, supposedly, moved on to bigger and better things. It was thought the game would flop. Amazingly, the game single-handedly revived the Game Boy, Nintendo’s handheld prospects, and ensured they would rule the handheld market for years to come.

What did they do so well to have created a game so popular and critically acclaimed? Other than the obvious effort placed in the product, it had a solid basis in Dragon Quest. To assume that these two were not influenced by Dragon Quest’s design would be severely shortsighted – surely, every JRPG designer played one or multiple copies by this point. Their design takes elements of Dragon Quest and improves them for the handheld format. Pokemon merely changes the setting of Dragon Quest…at first. Instead of being a hero in a idealized faux-European fantasy world, Pokemon establishes its world as one grounded in a similar technological state to our own. People have television, the internet, super markets, and just about every convenience of the modern world. They even have smart phones and electronic encyclopedias – how’s that for prefiguring future technology in the 1990s?

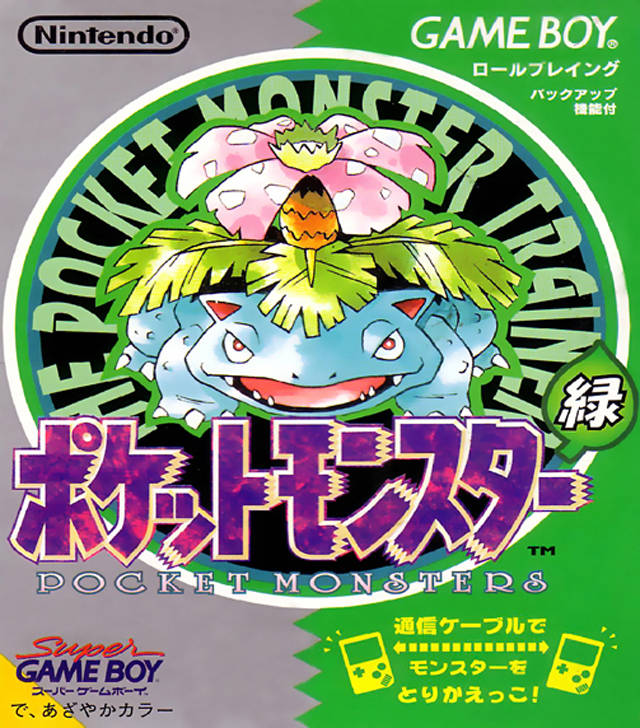

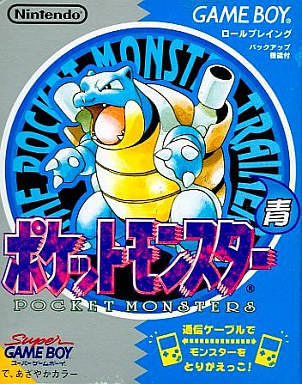

What they have that we don’t, however, are Pokemon. Short for “Pocket Monsters”, Pokemon exist as a vast array of diverse and magnificent creature which display basic intelligence. In America’s version of the cartoon, they can only speak their name repeatedly, though I suppose it doesn’t much matter – Pokemon can’t speak English or Japanese. They work in a symbiotic relationship with the human race, and this has given rise to a culture where Pokemon Trainers arose. Pokemon Trainers participate in rules-based fighting with their companions and train their Pokemon to see who’s the best. Apparently, the whole culture’s based around making animals fight each other – not that PETA hasn’t noticed. Still, it’s understood that Pokemon learn to love their trainers and don’t ever die during fights – they just faint – which was an intentional decision on the part of the developers to reduce the violence in video games. In fact, Tajiri only wanted the initial games to be Pokemon Red and Green, which are complementary colors, rather than Red and Blue, which connotes opposition. No surprise which versions were released in the United States first.

Unlike Dragon Quest, you aren’t going to save the world. Instead, you want to become the world’s greatest Pokemon trainer…and maybe save the world by accident with your animalistic companions. Like Dragon Quests of recent years, you obtain multiple party members, but these are by YOUR choice rather than the game’s choice. This makes a world of difference – decision making brings attachment to a game, especially when there’s lots of it. 151 Pokemon exist in the original game, and that was more than enough. Each has a unique look, type, and attacks. Catching wild Pokemon, you’ll find your own favorites, train them, and discover how they work and what moves are the most efficient. However, unlike Dragon Quest, there’s no upper limit to what you can learn.

To simplify: Pokemon = rock/paper/scissors with fifteen different types (or seventeen, in everything after the base game. This also fixes a notable flaw, which I’ll explain in a later installment). Pokemon learn abilities at points as they evolve, but they can only learn a maximum of four. This means you can’t learn every ability, and none become totally outdated – unlike Dragon Quest, there’s no massive accumulation of STUFF that means you win every battle. Surely, you need to grind to succeed by leveling up Pokemon, but you can’t have all the abilities in the world. This forces an element of decision making and strategy. Items can teach Pokemon abilities they wouldn’t learn otherwise, and each Pokemon type has its own weaknesses and strengths – there’s a LOT going on here, far more than Dragon Quest’s set and linear quest. You can grind past problems in DQ, but Pokemon types mean you need a balanced team overall – constant random battles can’t solve all your problems. The more you know about Pokemon, the easier your game becomes. Not even Pokemon weaknesses necessarily determine a fight – your Pokemon’s statistics can spell victory or defeat as well.

The plot isn’t the focus; rather, it’s the plot you create that counts. Your experience with your Pokemon becomes the narrative element; everything else is just fluff. In Dragon Quest, story elements and narrative add attachment to the characters. For the most part, however, once they join your party they virtually dissappear from the main story, save the occassional vignette or character development sequence. Pokemon allows you to identify and create your own team. In time, you’ll grow attached to the little critters because YOU built them from nothing. They fight for you with no regard to their safety, trusting that you’ll keep them alive in battle after battle. It’s no wonder the relationship aspect became more and more important in later games – identifying with your party’s teamwork remains an essential component to its addictive nature. It’s difficult to describe WHY this works, but it certainly relates to the hard work and effort required to succeed. If you put in the time, you can win. There’s a satisfacion that comes from building the perfect team, able to deal with any situation you please.

I am somewhat disappointed that there’s nearly no way to fail in the game if you play correctly (or incorrectly, as it turns out). The game provides leeway in nearly every aspect. Pokemon Centers allow you to heal your Pokemon to full; theoretically, you can just run back to one after every fight. Some caves make this much more difficulty, but they’re only a taste of Dragon Quest’s resource management model since you receive so much money. Then again, you will learn failure when your Pokemon faints, either because of a missed move/type mismatch/level disparity between the two Pokemon or otherwise. Pokemon compartmentalizes its failures in every battle rather than in the disdain of a Game Over screen. I’m not sure whether it’s the better for it, but it fits with the general theme of learning and growing without fear of total, massive failure.

A team can’t fail if the others can pick up the slack for your mistakes. Apparently, even Tajiri believes Westerners understand his series better than the Japanese. It’s not about Pikachu, but the idea of partnership and friendship. Teamwork makes success, not just the one great Pokemon. None of them are perfect, but each has a role to play in any Pokemon team. “Game and gamer” interact and create a space for experimentation, excitement, and challenge. The social element isn’t limited to the digital creatures alone, however. The true reason for success was the community that still surrounds this special series.

Continue to Part 3