Last updated on December 30, 2013

23 And He was saying to them all, “If anyone wishes to come after Me, he must deny himself, and take up his cross daily and follow Me. 24 For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake, he is the one who will save it. 25 For what is a man profited if he gains the whole world, and loses or forfeits himself? 26 For whoever is ashamed of Me and My words, the Son of Man will be ashamed of him when He comes in His glory, and the glory of the Father and of the holy angels. 27 But I say to you truthfully, there are some of those standing here who will not taste death until they see the kingdom of God.”

Luke 9

The Bible constantly asks us to deny ourselves. Notice the giant Author tab above the article here, and you’ll not that we list our authors out. We have a tiny author box at the bottom, just in case you didn’t know. However, I find that with the advent of the Internet, it’s often that the majority of content turns up without a specific author attached. Those that do end up with special significance. I would hope that my name slapped on so many articles doesn’t somehow establish me as important. The concept of Theology Gaming, as a theological investigation of video games and their culture from a variety of different angles, is what I hope to see. A diversity of authors goes a long way in crafting a voice that isn’t ruled by dictatorship to a particular creed, except that of the Gospel. I do hope Theology Gaming remains self-effacing without some strange sort of mascot made out of my various online masks.

In that respect, my hope for Theology Gaming isn’t Zach’s Domain of Opinions, but something interesting to read that might make you think a different way, or open up to a world of different experiences. Of course, you will find my personal opinion dripping throughout the various subject matters I cover, but that’s part and parcel of writing. Unless, say, you craft specific rules that force subjectivity out of the process, a piece of missing information here or there.

That has not happened in the main circles of video game writing. We desire to associate something with someone, if not by name than by website. In our case, video game websites get associated with a specific voice or message. Sometimes, that message turns into the shrill cries of social justice (Polygon and Rock Paper Shotgun come immediately to mind) while others just review games as products (IGN and Gamespot). Both represent different sides of how to approach video games journalism, with mixed results.

However, as we go on with this whole business of video games, I am finding that the distinctive authorial voice turns into more an excuse to attach something to someone. I get the urge: we want someone to respect, to “look up” and see how to better ourselves. But why do we seek so fast to straitjacket a new form of entertainment into the mold of the old, consciously or not? We often like to identify indie game auteurs, or highlight their Independence, or some such other thing. Why should it be this way? Why the Western cultural hegemony? Certainly, the East produced video games as well!

Video games don’t fit into the neat categories of “author”, “directors”, and the like. Video games often fall into the category of a “self-effacing work”. Since their beginnings, the medium emerged out of the efforts of teams both large and small, contributions from disparate fields from both the humanities and the sciences, as well as a wide variety of involved parties. Each one places their particular mark on the whole, and who can identify the parts?

Unlike, say, the director of a film or the author of a novel, the director of a video game doesn’t often retain the creative control that you would imagine. Any director seeking to improve his craft and design will see problems emerge from their initial ideas and troubleshoot through them.

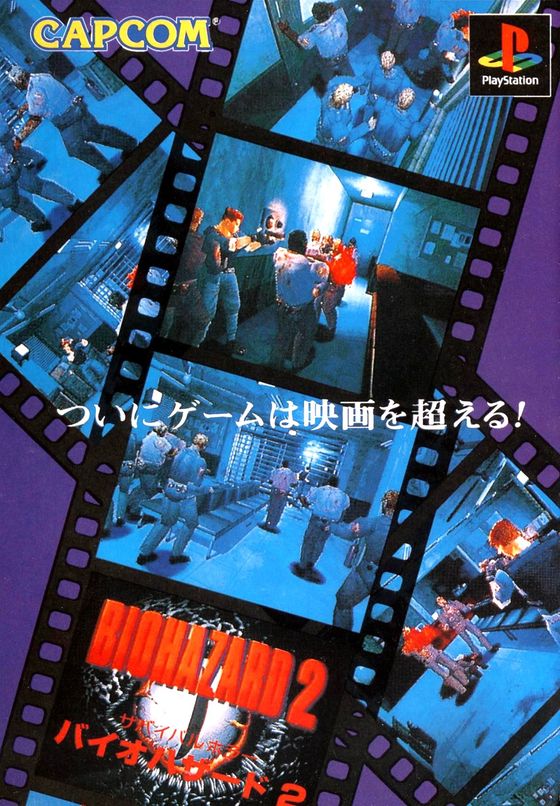

I think of one of my favorite directors, Hideki Kamiya. His games never feel like solely his work, since you can see Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami’s hand in much of his pre-Devil May Cry output. For example, Devil May Cry’s basic style borrowed heavily from Resident Evil 1.5, the developed sequel to Resident Evil. Intended as a more action-heavy follow-up, Capcom found this version much too divergent from the original product. Thus, they forced him to cancel it and produce what we now know as Resident Evil 2 in its place – not a bad game, of course, but certainly not the game Kamiya wanted to make. Mikami knew that such a product would disappoint the fans of the original, and as executive producer he could make the sort of tough decision that scraps a 80% complete product for a far superior offering.

However, Mikami didn’t discourage Kamiya to make the game he wanted to make; it just didn’t fit within that series in particular. When the same issue emerged again in the development of Resident Evil 4, with Kamiya at the helm, Mikami saw the burgeoning development of the new title. It involved the same pre-rendered backgrounds and added a dynamic camera, yet it also contained a gothic castle with elements reminiscent of fantasy than anything approaching Resident Evil. The protagonist, Tony, used his genetically manipulated body to perform stylish action moves and cool combat sequences.

Mikami saw this wouldn’t work, and so did the rest of the team. Resident Evil wasn’t the right place for this sort of experience, and so the scenario writer changed the setting to what we know as Devil May Cry today. Elements of this initial game would go on to influence the more action-heavy, dynamic feel of Resident Evil 4. Each one shows a give and take in the process of collaboration.

Imagine just taking a cursory look at the Devil May Cry series, and you would imagine Kamiya as the sole person responsible for the long gestation process. Yet, it’s obvious that a lot of input and creative freedom emerged as games came into development as one idea and emerged as another. Can you imagine a film that would suddenly turn into this with scenes already shot, or a book that completely rewrites the plot into a new setting? You may as well start over. Not so with video games! A good idea is still a good idea, and one can transplant mechanics from one game to another.

In that sense, it is odd that video games progress towards the “auteur” approach, rather than the company from which they derived. I honestly always associated Devil May Cry with Capcom, as no one ever told us who directed what. We didn’t really care; if the game was good, it was good, and we’d accept that the collaborative efforts of Capcom produced this distinctive game from that company. Many different styles came out of that studio, yet all remained Capcom games. When I found out Hideki Kamiya and Shinji Mikami made many of the games I liked and enjoyed, that was merely coincidence.

In other, more succinct words: the game came first, rather than the pride of the singular director. Perhaps it comes from the collectivist nature of Eastern cultures versus their Western counterparts, but there’s a self-effacing virtue ethic to the design of Japanese video games that you don’t find in the West. No Phil Fishs or Jonathan Blows, no people making grand statements about how games should be designed. All they show us is people making games. I prefer this approach, a last bastion of accomplishments not falling under a single name just because.

In that sense, it reminds me of Foucauldian epistemology. In epistemology, literally “the study of knowledge”, many questions come down to the ultimate: how do we know? That question, more often than not, appears literally impossible to answer. So many different interpretations and ideas come out of the enterprise, both from philosophy and otherwise, that sifting through it all isn’t possible.

However, in our case, we merely need to attach a methodology: why do I find the idea of self-effacement attractive? It turns video game development into an area less suited for pride, for the auteur, and rather for the product, the game itself, to demonstrate its own great qualities. Most entertainment does not provide us with the opportunity to dive into new experiences without some baggage, and video games held the line in this sense for quite a long time. That’s why I find Foucault’s approach in epistemology as startlingly accurate (at least in video games).

So, for next time! (or next Friday, whatever).