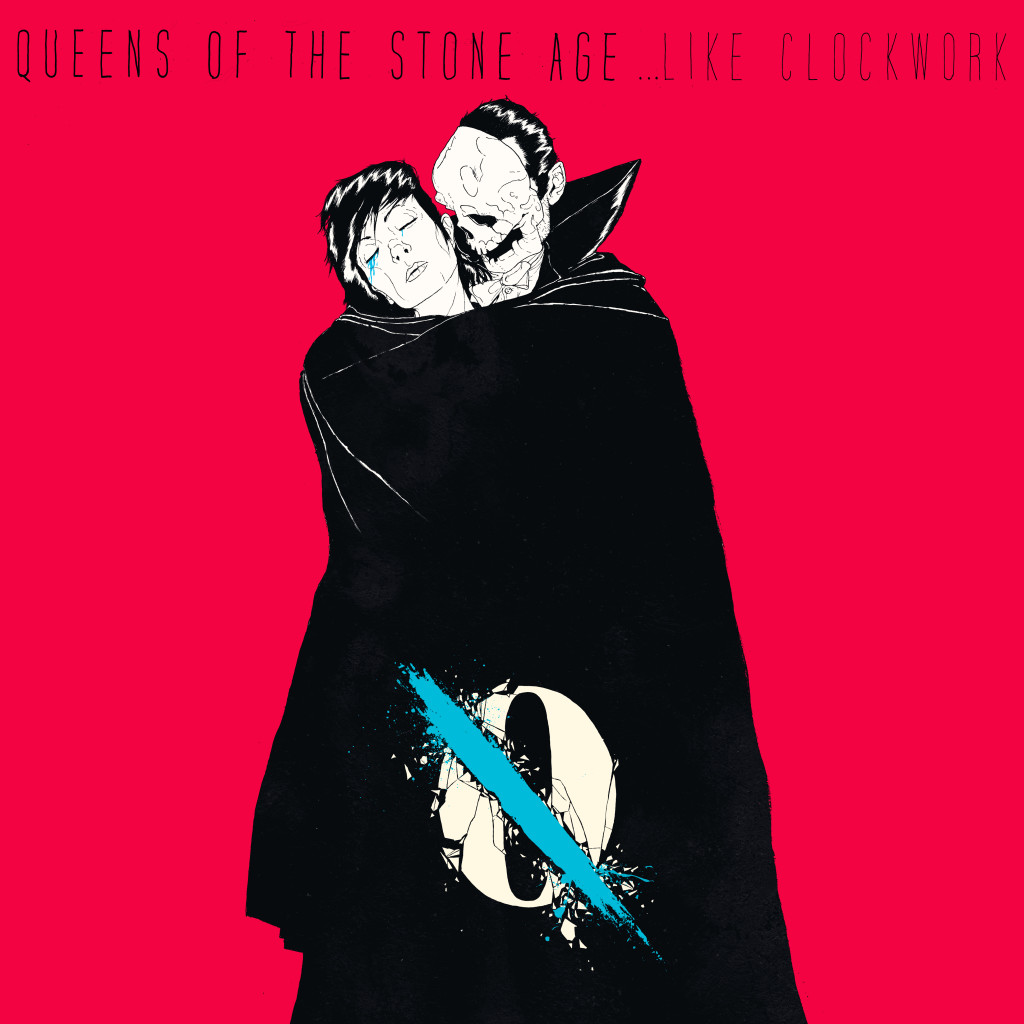

I’m a man of a normal upbringing and strange tastes; teaching your children to think independantly of everyone else both retains its perks and its disadvanatages, I suppose. While many other people received their first musical christening from above through some such indie band or Radiohead, God deigned to give me a taste of the Queens of the Stone Age instead. Why dirty, nasty robot rock? I honestly couldn’t tell you, but there’s a aesthetic, a mood, a style of lyrics, and a focused purpose that lends me to listen to whatever Josh Homme’s brainchild trust spits out. That counts Them Crooked Vultures and any number of even tertiary related properties (Eagles of Death Metal, The Dead Weather, Foo Fighters, etc).

Until the coming of Rock Band, I was literally ignorant of good music in general; I say that with the highest respect to myself circa 2008 -who, if I’m being honest, was rather a bore and a bit droll. Playing “Go with the Flow” caught my attention – the repetitive riffs, the chugging pace, the weirdly guttural and yet falsetto voice of Josh Homme. Lyrics formed images and puzzling-headscratchers; you do not listen so much for the “meaning” as for the feeling.

Frankly, it stunned me a little. I liked the song, sure, but it felt a little anemic by itself. Maybe a full album could really capture something amazing? I picked up Songs for the Deaf a couple months later, but I really hated the album. I tried to listen to it, but I just didn’t “get it” at all. That’s a frustrating experience (much like playing SaGa games – sorry Pat Gann!) The album just switches genres at the top of a hat; there’s no real consistency at all other than the quirky radio interludes. I kept listening to it, though; there was something intriguing about this music that I couldn’t quite resist.

However, one day it just clicked. For lack of a better description, banging my head against the wall brought its own “eureka!” moment with it. Every song became a delight, and the album’s flow (har har) went perfectly. Like a long and lonely drive through the desert of Southwest America, Songs for the Death creates a tension-filled ambience. Even with lighter fare inbetween the more focused “rock” songs, it still manages to evoke a particular feeling. That’s even more amazing given the depth of guest contributions (everybody from former band members to Elton John, somehow) and the exemplary chops on display.

Homme, thankfully, is willing to try anything within the context of “rock” music. Initially described as “robot rock”, the basic template become twisted, contorted, and mangled under a singular vision and mood. Rated R smacks of a bad acid trip. Lullabies for the Paralyzed evokes the atmosphere of a dark Brothers Grimm fairytale, while Era Vulgaris goes into the dark underbelly of Hollywood, equal parts meaningless pleasure and harrowing consequence I hesitate to mention specific songs, simply because turning QOTSA into “best single!” doesn’t work. Each song makes sense in lieu of the whole, and I find it meaningless to identify a best song.

In sum, QOTSA tries to convey a particular mood and feeling through a variety of sources. Each experience sounds different, both musically, sonically, and lyrically, yet retains some sort of feeling about actual life that you cannot quite express in any other sense. Good art should perform precisely that function: to show us something of reality that we cannot see otherwise in another more rout format (say, public speaking or conversation). If you want the title of “poet”, make sure the medium represents your message better than anything else. If you want “video game developer” on your artistic achievements resume, make sure that video games truly represent this.

Now, you’ll notice that nowhere in the above description did I tend to describe QOTSA’s appeal in terms of “meaning”. To insert meaning into artistic works actually comes from a modern context rather than one inimical to the mediums themselves. It should not surprise you that we tend to analyze everything in popular culture and make a business of it. It prevents people like me from doing something honest or noteworthy for a living, but it also reveals a stunning tendency to take one aspect of a work in deference to everything else.

Rather than take the work at face value, we tend to insert ourselves or find ourselves in it instead. This seems extremely odd from a Christian perspective – rather than letting something speak for itself and describe a common reality for all humanity, you place your own tendencies, ideas, and values into the work. Unsurprisingly, what you find in the work ends up being yourself, a self-reflecting narcissistic mirror. To take an example from The Christian Shakesepare‘s Kevin O’Brien:

This is why, while preparing a scene from The Merchant of Venicefor the EWTN series The Quest for Shakespeare, hosted by Joseph Pearce, one of my young actors told me that, “You know, the two main male characters in this play, Antonio and Bassanio, are gay lovers.”

Aghast, I countered, “There is not the slightest bit of evidence for that in the text. The love that these men have for one another is the love of friendship, something that would necessarily exclude any genital encounter between them. It’s incredible even to suggest such a thing. Have you ever been in any production of this play that actually tried to sell to the audience this crazy notion?” (Editor’s Note: I’d say Jonathan and David from I Samuel fit into the same context as well, to throw a Bible reference into the subject matter)He looked at me with the kind of patronizing pity that can only be expressed by a young man frustrated with an old man who is sliding into his dotage and who just doesn’t get it. He smiled and patiently explained, “I’ve never been in a production of The Merchant of Venice where their relationship was presented in any other way. They are clearly gay lovers.”And that’s the new tradition. That’s the way the show is now being produced.

For my point is this…you cannot begin to understand life – you cannot begin to be grateful for life – you cannot begin to approach life – until you learn how to read – how to read a book, how to read a play, how to read a movie, how to read your friends, how to read the Great Book of Being written by and filled by the Incarnate Word of God.

I will give Mr. Shaw three lines out of As You Like It from the exquisite and irrational song of Hymen at the end:

Then is there mirth in Heaven

When earthly things made even

Atone together.Limit the matter to the single incomparable line, “When earthly things made even.” And I defy Mr. Shaw to say which is matter and which is manner. … If the words, “When earthly things made even” were presented to us in the form of, “When terrestrial affairs are reduced to an equilibrium,” the meaning would not merely have been spoilt, the meaning would have entirely disappeared. This identity between the matter and the manner is simply the definition of poetry. The aim of good prose words is to mean what they say. The aim of good poetical words is to mean what they do not say.

A bad Christianity makes us settle for the earth when we could have the moon. We limit our own sense to appreciate things when we break them into constituents details. A theological myopia creates all sorts of terrible errors of the worst kinds; any cursory look of human history proves that right out of the gate. Rather, we need a broad and wide perspective that unites all of these seemingly disparate elements.

If you believe anything at all of the theological sort, we automatically assume the inter-connectedness of things; after all, God created everything. We take that creation story far too lightly at times, and we look with near-sighted bewilderment when something breaks our own personal bubble. We make Genesis 1 less powerful.

26 Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

27 So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

28 God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule overthe fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”

Although it portrays a message of dominion and stewardship, we are created in the image of God as well. We are expected to look at reality with the same perspective because we work and move in the same fashion as the creator. To focus on one particular aspect of reality (the knowledge of good and evil) and remove all the other wonders of life (the Garden and God’s creation in itself) gets us into dire straits. Our responsibility lies in creating new ideas, new forms of expression that expand our world.

We shouldn’t be getting too used to the stars in the sky, but see them new every day.