Last updated on July 20, 2016

For those of us who play a LOT of Japanese video games, translation and localization seem like ubiquitous issues.

Video games are a funny thing when they start crossing cultural barriers. Since the majority of the games of my childhood actually came from a different country, you don’t realize this until you look back at the games themselves. Prior to the late 1980s, of course, little translation was necessary to get a game up to speed in America, but the increasing popularity of JRPGs meant that translation and localization would become essential to the presence of Japanese games in the market. At that point, standards of quality were, shall we say, low. No game better demonstrates this, in my mind, than Capcom’s Breath of Fire series.

Breath of Fire tried to capitalize on “JRPG” fever by, well, creating a SNES Dragon Quest clone with a few minor enhancements here and there. Add Capcom’s graphical polish, and you’re left with a rather rote, if entertaining, JRPG experience. However, Capcom rightfully knew they couldn’t bring the game over to the West and expect success without some kind of translation or localization team – it’s not like Capcom games at this point demanded exhaustive, RPG-length scripts, so they lacked the internal mechanisms necessary to make it happen.

Enter Squaresoft! A deal was struck between the two wherein they’d share the profits, and the more experienced company (at least for the purpose of translation and localization) would promote, publish, and fix the game for Western release. Unsurprisingly, Ted Woolsey handled the majority of the script – love him or hate him, you do remember him at least for “spoony bard”. His version of the game strikes me more as a “localization” – that is, the game’s adapted for a different cultural context by bringing the dialogue into English, specifically American, colloquialisms and the like. The vast majority of video games from Japan fit into this category, for good or ill.

Breath of Fire came out during Squaresoft’s 1990s heyday, so it should not shock you that it became a bit of a surprise success, at least in 1994 terms (that’s a year from its Japanese release – these things took a long time back in the day!). We can assume that’s partly due to Squaresoft branding, being THE RPG company in console gamer circles at the time. Having had a copy of the original box, Capcom’s name barely even appears except on a tiny portion of the back! That doesn’t mean the game itself wasn’t a quality title, just that a little push like a solid localization helps out a lot (and maybe a well-known brand name too).

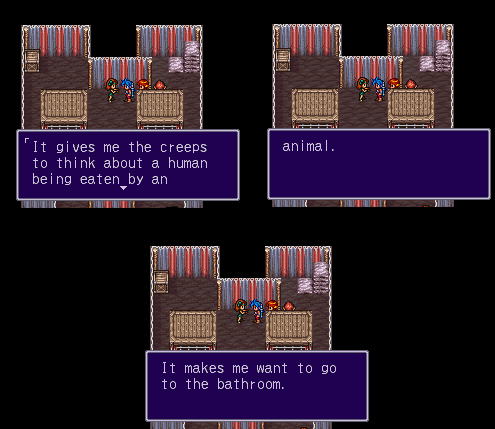

However, the cat leaped directly out of the bag once Breath of Fire II came to Western shores. The same development team helmed the ship of this direct sequel, but Capcom decided to leave Squaresoft out of the equation for the translation/localization efforts. Instead, they put Capcom USA in charge, and that may not have been a good idea! For all intents and purposes, I can say that, having played the original release a lot, it’s absolutely terrible. Honestly, parts of the dialogue make zero sense at points, and discerning the plot can be a chore and a half. It’s like someone put the entire game through Google Translate or something, without bothering to actually double check anything.

The game still sold well, but the fact that it later received a “re-translation patch” tells you a lot about how pleasant this is to actually play (i.e., if you’re playing any official release of the game, it’s still a bungled mess). It goes without saying that “Yes” and “No” are often swapped, just to add insult to injury and actually affecting the game! To put it a little more succinctly, as the re-translator himself says:

The old translation is a stilted, mechanical mess. It’s not as bad as Zero Wing – at the very least, it tries to abide by the conventions of English grammar – but imagine running an entire script through Babelfish, if Babelfish could be trusted not to completely mangle every single sentence put through it. That’s BoFII‘s translation in a nutshell: a slavish, artificial-sounding, word-for-word conversion from the Japanese script to English. Contrary to rumor, there are no vast swaths of script missing from the English version–just a few minor things that didn’t get past Nintendo’s censors–but there’s no regard for aesthetics, either.

For more fun examples of this, a link has been provided! Such choice bits as “A machine and a dandy man. It’s too much!” are hard to resist!

Anyway, long story short: a slavish, word-for-word translation didn’t exactly work so well for Breath of Fire II. And, for most games, it turns out a word-for-word translation does not make for a good game by necessity. I’m sure we’ve all heard the argument that such a process would automatically improve certain video games, but there’s a few reason beyond the Breath of Fire II example that this might not be the case. First, translating from one language to another directly means you’ll just be missing certain words and phrases that make sense in another language. Second, a direct translation does not often make sense when translating from Japanese to English, or pretty much any language derived from Germanic cultures (as English often is). Lastly, a direct translation is often unexciting, or just simply nonsensical from ship to stern.

I suppose those are all generalized statements, but it does reveal one thing: localization will remain necessary for a long time to come. Not only does it make a game more accessible to a completely different culture, but it also broadens the appeal of a game to new audiences. And, I think, this is the same process of Biblical translations as well. Just comparing the King James Version to more recent translations, we can see clear discrepancies between the two. For more of these, see here, but I’m going to steal a few for my own purposes:

Matthew 26:63-64

But Jesus remained silent. The high priest said to him, ”I charge you under oath by the living God: Tell us if you are the Christ, the Son of God.” 64 ”Yes, it is as you say,” Jesus replied.

The New International Version

Matthew 26:63-64

But Jesus held his peace. And the high priest answered and said unto him, I adjure thee by the living God, that thou tell us whether thou be the Christ, the Son of God. 64 Jesus saith unto him, Thou hast said.

The King James Version

Remember that the New International Version is a “thought-for-thought” translation – that is, it does not stay on literal adherence to the text itself, but rather tries to convey the intended meaning of the verse without too much in the way of interpretation. The King James Version, on the other hand, is the first of the “word-for-word” English translations, and in that sense proves very complicated to read. The syntax in the NIV version above makes it clear that Jesus is saying “I am the Christ, the Son of God”; the KJV is much less clear in localizing the Greek idiom planted here (i.e., “what you have said is true), instead stating “Thou hast said”…what? For the modern reader with modern English syntax, it just doesn’t have the same emphasis or sense as the NIV does. Note the direct translation doesn’t exactly fix the problem here.

Now, to compare two “word-for-word” translations:

Hebrews 1:3

And He [Jesus] is the radiance of His [God’s] glory and the exact representation of His

nature, and upholds all things by the word of His power. When He had made purification of sins, He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high;

The New American Standard Bible

Hebrews 1:3

Who being the brightness of his glory, and the express image of his person, and upholding all things by the word of his power, when he had by himself purged our sins, sat down on the right hand of the Majesty on high;

The King James Version

Technically, both say the same thing – that Jesus is the radiance/brightness of God’s glory. But the second part of that sentence means very different thing! That he either is an exact representation of God’s nature or an expression of God’s person constitutes two very different meanings to the modern reader, despite both being in English. The KJV here hasn’t aged very well, failing to indicate with enough emphasis that the author of Hebrews means that Jesus is God and has his nature. While both the KJV and NASB both render the sentence into English, one was written for a very different time period and context which loses that context after nearly five hundred years. The modern reader gets a better sense of the meaning via the new translation.

But, is it always the case that “localization” involves “translation”? Absolutely not! That’s where we get into more ambiguous territory…