Last updated on December 19, 2013

7 For God has not given us a spirit of timidity, but of power and love and discipline.

2 Timothy 1

Is it just me or did video games become rather dark all of a sudden?

Just wandering around GameStop today, I noticed that most, if not all, the games highly anticipated in the “gamer” world involved dark and gritty worlds, a host of violence, or some sort of psychological/emotional trauma. We live in a brave new world, apparently, where our entertainment choices reflect a preoccupation with dark themes and ideas. That surprises me, even when statistics indicate that the market for our common digital entertainment of choice almost skews fifty-fifty between males and females (60-40 is probably more accurate, but you get the idea).

Perhaps we need artsy film, and dark environments where we make horrible decisions? See Far Cry 3, or Spec Ops: The Line, or everyone’s favorite Call of Duty (whichever one, there’s too many of them), or any number of other first/third persons shooters released over the last half decade. Something’s clearly changed in our ideas of what constitutes fulfilling and interesting entertainment. Heck, even our science fiction and fantasy shoot for the “low” end of the spectrum (you know, in respect to high fantasy). Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Fallout, and Elder Scrolls clearly don’t fit into the same “heroes of light” mold as Final Fantasy.

Did Grand Theft Auto IV necessarily dictate this trend? Possiblty! I’ve always imagined that GTAIII changed the market by introducing a violent open world that actually functioned well in a game, but the influx of open worlds didn’t change the general vibe. Worlds existed for fun and enjoyment; a little dark humor didn’t hurt because GTAIII reveled in how dumb and unrealistic its shootouts, physics, and narrative were. Its story borrowed tropes from a hundred crime films, smashed them together without any cohesion, and made sure you knew it reflected its influences in sardonic Quentin Tarantino situations that you controlled.

But Grand Theft Auto IV created a rather restrictive playground that took itself mighty seriously. The story morphed into something meant to be applauded, lauded, and understood as a realistic commentary on crime. Then, you’d go out and shoot people in the streets after lamenting one person’s death. Clearly, that story clashed with the traditional Grand Theft Auto formula – you gave us an open world, Rockstar, but you wouldn’t let us play with the tools. The Housers turned Grand Theft Auto into a American cultural commentary mill with more misses than hits, and it’s quite a shame (they also did that to Max Payne).

I guess I could give Bioshock some credit here, but Bioshock’s plot is infinitely more creative and interestingly than GTAIV, even if it only rises to the level of surface commentary. Games rely on settings like films rely on scripts and visual cues/editing; unfortunately, depth and exploration of environment, what video games do best, find themselves completely ignored at the altar of the blockbuster.

I imagine GTAIV really sparked this trend in dark narratives. Developers need to experiment, obviously, or else it will die. If such a game represents the pinnacle of the medium, with a 98 MetaCritic score, why would you not expect everyone else to follow in those footsteps? To place this at its most base: video games themselves did not arise out of the need for artistic expression. Rather, they emerged as products for consumption and enjoyment, as well as providing marketing departments with methodologies to create that desire for fun, prolong it, and sustain it. And then make you buy it again when a new installment emerges. Activision’s exploitation and disposal of whatever franchise happens to bring in a profit shows us the results of the capitalist game at play.

My worry, then, stems less from market trends and more about what these mainstream games represent: a strange obsession with realistic conflict, emotional trauma, and utter darkness. We don’t call it “immorality” anymore, and we will keep pushing those boundaries until they break. It’s just the nature of the sinful world, I suppose, but there’s a deeper reason. Modern culture makes it increasingly difficult to experience what happens in games. How many people in my generation, for example, found the government drafting them into the Iraq War? The answer, from what I can tell, is zero. The United States Military’s run entirely on volunteers, far as I know.

So what happens instead? Military shooters reign supreme. We play at real experiences, only to fail at recreating them. Heck, just take a look at any David Cage game, with their uncanny valleys and scary attempts to “replicate” real life strike me as really, really creepy. Perhaps I come from a nostalgic point of view, but my game time comes from playing new experience that couldn’t exist in the real world. I want to jump on turtle heads and you won’t stop me! That strange absurdity in video games turns into a common point of discussion, hilarity, and friendships. That’s what video games mean to me. Heck, I talk about them more than I play them, let’s be honest about that. They exist as a vehicle for human interaction and action, not as a replacement of it.

Looks like I’m about to lose my street cred, because I AM going to link that Mark Driscoll video that “gamers” hate:

Honestly, I must agree: video games, as understood in the American mainstream sense, are stupid. When games transform into vicarious recreations of real battle, conflicts, emotions, and otherwise, we forsake the actual for the virtual. When it’s a replacement for human life, then it becomes a problem. But that’s not just limited to MMOs; even a “literary” experience or indie game meant to convey a concept falls into the same mold. It’s the vicarious nature of the whole enterprise that makes video games such a double-edged sword – fall to either side, whether to not play at all or to wholly invest ends up with a bloody mess.

We are the culture of continual commentary where the consumers comment on the producers, and soon there won’t be anything left to consume. We need vicarious experience because, let’s face it, we would rather say than do. It’s easier for me to sit here and type on a computer, or argue with someone on Facebook than to do something. The Bible’s full of people doing things; seriously, how many physical battles are there in the Bible? A lot. How much of the story involves people sitting around, vicariously experiencing emotions or expressing themselves in any vein but devotion to God? Do the alternatives look like they ever represented “self” above all else?

So we have vicarious experience on one end, or people making games expressing “themselves” on the other – it’s really all the same. These impulses to create get mixed up with human fallibility, and even writings like the one you are reading now fail to point quite correctly to God. It’s mere gesticulating, at a point. They’re not true stories, not that every story should exist in the same framework as God’s story, but it should point there.

This, to me, shows why Chesterton’s defense of the “vulgar” popular literature of his time shows us how far we have fallen. Our popular literature looks the same as his elitist literature, and what he has to say looks none-too flattering:

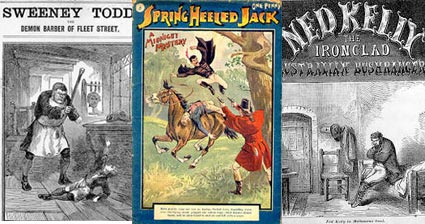

One of the strangest examples of the degree to which ordinary life is undervalued is the example of popular literature, the vast mass of which we contentedly describe as vulgar. The boy’s novelette may be ignorant in a literary sense, which is only like saying that a modern novel is ignorant in the chemical sense, or the economic sense, or the astronomical sense; but it is not vulgar intrinsically—it is the actual centre of a million flaming imaginations. . . . The simple need for some kind of ideal world in which fictitious persons play an unhampered part is infinitely deeper and older than the rules of good art, and much more important. Every one of us in childhood has constructed such an invisible dramatis personæ, but it never occurred to our nurses to correct the composition by careful comparison with Balzac. In the East the professional story-teller goes from village to village with a small carpet; and I wish sincerely that anyone had the moral courage to spread that carpet and sit on it in Ludgate Circus. But it is not probable that all the tales of the carpet-bearer are little gems of original artistic workmanship. Literature and fiction are two entirely different things. Literature is a luxury; fiction is a necessity. A work of art can hardly be too short, for its climax is its merit. A story can never be too long, for its conclusion is merely to be deplored, like the last halfpenny or the last pipelight. And so, while the increase of the artistic conscience tends in more ambitious works to brevity and impressionism, voluminous industry still marks the producer of the true romantic trash. There was no end to the ballads of Robin Hood; there is no end to the volumes about Dick Deadshot and the Avenging Nine. These two heroes are deliberately conceived as immortal.

It is the modern literature of the educated, not of the uneducated, which is avowedly and aggressively criminal. Books recommending profligacy and pessimism, at which the high-souled errand-boy would shudder, lie upon all our drawing-room tables. If the dirtiest old owner of the dirtiest old bookstall in Whitechapel dared to display works really recommending polygamy or suicide, his stock would be seized by the police. These things are our luxuries. And with a hypocrisy so ludicrous as to be almost unparalleled in history, we rate the gutter-boys for their immorality at the very time that we are discussing (with equivocal German Professors) whether morality is valid at all. At the very instant that we curse the Penny Dreadful for encouraging thefts upon property, we canvass the proposition that all property is theft. At the very instant we accuse it (quite unjustly) of lubricity and indecency, we are cheerfully reading philosophies which glory in lubricity and indecency. At the very instant that we charge it with encouraging the young to destroy life, we are placidly discussing whether life is worth preserving.

But it is we who are the morbid exceptions; it is we who are the criminal class. This should be our great comfort. The vast mass of humanity, with their vast mass of idle books and idle words, have never doubted and never will doubt that courage is splendid, that fidelity is noble, that distressed ladies should be rescued, and vanquished enemies spared.

Our modern stories inspire us to inaction, not service. That is exactly the problem! The world cannot show us stories of eternal hope, of an eschatological hope, because…well, there’s a point in time, little Jimmy, where you’ll fade into nonexistence. Mortality and the fear of death remains the great anxiety of our age; no wonder we place the aged in nursing homes so we don’t see the old people. We plaster ourselves with fake lives to bolster our self-esteem, but that fear never escapes us. Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die. Guess you shouldn’t expect such things to reflect a Christian worldview, but is it ever obvious now.

We need Christian art that reflects this, and we’ve completely lost it. We need it back, or else we go backsliding.