Last updated on March 4, 2013

Continuing E3 coverage! Wow, am I behind. Let’s get cracking.

While this all seems ridiculous Antoniades insists that this new version of Devil May Cry is a more sincere approach to the series. “It’s more grounded in some ways,” he says. “You could say it’s more serious.” The individual elements are still ludicrous, but it deals with more real world themes like media and government control.

Antoniades explains that, “the satire is a rebellion of establishment. It harkens back to a post-punk period.” 28 Days Later and Enslaved scribe Alex Garland is on board as a story consultant, so the narrative aspects that made the previous titles embarrassing to play around polite society should see a vast improvement. “Story is very important to us,” adds Antoniades, who explains that they’re using Giant Studios, the motion capture company behind Avatar, to help bring this tale to life.

I think you’ll know coming into this post that I am entering the conversation with a lot of bias. Still, I can’t help but comment regarding the idea of a Devil May Cry game with a great – and if I were more cautious, good – story. Honestly, that’s strange to me in more ways than one. Just because it’s weird, though, doesn’t mean their approach to the series is wrong. However, I think that the subject matter of Devil May Cry – that is, stylish 3D action with flair, pizzaz, demon slaying, and just about any other cool thing you can cram into a game – doesn’t allow for such devices to have any place in the series, as much as any developer might shoehorn that content within the game’s structure.

Now, a good narrative in a game, for me, works on a secondary level. If it’s not there, I am totally fine with that. Not every game needs to become the narrative phenomenon of the century to win me over. My standards for game stories are substantially low because I entered the hobby during its earliest years. Having a confusing nonsensical narrative like, say, Final Fantasy IV was perfectly functional for its time. The fact that the end of the game takes place on the moon for some reason, and moon people (Lunarians) someone dicatated the problems on earth doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm for how borderline stupid it sounds. In other words, there’s the good kind of stupid (intentional, or just workable given the subject matter), and the bad kind of stupid (unintetional humor, still funny but not for the right reason).

Devil May Cry is the good kind of stupid. It’s the intentional kind. The reason why Dante was such a striking character wasn’t that he was deep, interesting, or engaging; it was because he basically embodied every 1980s action movie star rolled into one guy who could, literally, do anything. No situation was too serious or deadly for Dante to pull some creative one-liner onto a giant magma spider. His cockiness wasn’t unfounded, either, if the player of the game was any good at playing the game. As far as wish fulfillment goes, it’s pretty much perfect. I’m not sure, then, why I should care that Devil May Cry would be “embarrassing” to play around polite society. What gives? Who in their right mind would take any of this stuff seriously? It’s fun! It’s not grounded; it’s flying into space at a million miles an hour while quipping “Not fast enough for me!”

Dumb fun works just as well as intelligent fun, in fact. God doesn’t hate fun, contrary to popular belief. If the New Testament teaches anything, it’s that the intention of the action counts for as much as the action itself. Matthew 5:27-30 says as much:

“ You have heard that it was said, ‘ You shall not commit adultery’; 28 but I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust for her has already committed adultery with her in his heart. 29 If your right eye makes you stumble, tear it out and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. 30 If your right hand makes you stumble, cut it off and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to go into hell.

You can see, here, that intention counts for everything. If we were to apply this to video games, then the intention remains more important than the setting. But we can see the new developers has taken the exact wrong lesson from the game: setting takes precedence over the original intention. Devil May Cry, then, has always been about serious action, certainly, but the morose and downbeat presentation remains a pretense and setting for crazy things to happen. When Dante rides a rocket, for example, it’s difficult to take seriously, nor would I want to take it seriously. Like Bayonetta, Kamiya’s creation was intended to be “cool” and fun, not dreary, boring, or an exploration of the ethics of censorship. It’s an effort in contrasts that works because it makes the action “pop” off the screen.

That’s like smuggling the whole John Galt speech into the Atlas Shrugged movie (doesn’t exist yet, but a literary metaphor as good as any); it’s preachy, pretensious, and gets in the way of what’s important. So we come to DmC, the cool new reboot of the series. So, what would be your first step in “reviving” the series? Firstly, I would not do this:

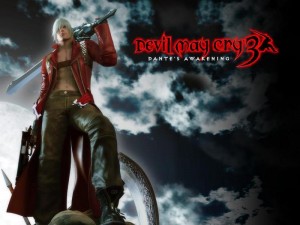

Seriously, why does Dante, our hip devil-slaying protagonist, have to look like this for a serious story? Compare the original Dante:

Obviously, my choice of screenshot highlights a not-so-subtle difference between the two versions. The former, apparently, has decided that the requisite “emo cut of the day” fits a serious narrative better, whereas the latter is having a great deal of fun being a nearly immortal, half-man, half-demon dangerous combat machine. Devil May Cry, for its dark setting, tone, and enemies, has a weirdly light-hearted character (excluding the apocryphal DMC2).

So, when I heard they were taking the series in a “dark” direction, I could only think: it’s already pretty dark when the main objective of the villain is to open the gates of Hell, wouldn’t you think? When we say “dark”, then, we’re moving into the same territory as “edgy” – i.e., we, as the developers, are trying to figure out what all the kids think are hip and cool, and cram as much of that as possible. That’s not “sincere”, my dear friends at Ninja Theory; that’s what we in the world of reality and marketing call “appealing to your audience”. And, that’s what the more artistic types call “pandering”.

Taken in that sense, then, it’s hard to reconcile the theme of “media and information control” with “giant demons who want to kill you”, with a little spice of “totally awesome demonslayer”. Are you seeing the problem yet? Even the young Dante shown in Devil May Cry 3 is, at the very least, consistent with the wisecracking, fun-loving Dante of the later games.

Still, I don’t have much of a problem with the new protagonist in terms of design; it’s fine, though I’m a fan of the 80s rocker look, but it’s definitely more modern and less retro than Dante’s previous design. What I am worried about, then, is this design taken seriously in a serious story that, somehow, wants to say something meaningful while at the same time having ultra-rad combat sequences. I just don’t see how that can work out well. The layering of the new themes onto an existing framework looks contradictory right from the start, and that’s pretty troubling. Ninja Theory, then, conflates the setting with the intentions, and that can’t be good.